The secret life of the gas station

I’ve read a lot of business books and I have to say that The Secret Life of Groceries now ranks in my top four. It’s right up there with Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of General Electric, Shoe Dog, and the Enron book by Bethany McLean, Smartest Guys in the Room. Benjamin Lorr spent over four years working alongside the army of the invisible who feed us every day. Lorr introduces readers to the groundbreaking approach of Trader Joe, but quickly descends into the harrowing world of industrial fishing where human slavery still exists. The indentured servitude faced by many long-haul truck drivers is only slightly more uplifting. You can learn about the battle for shelf space by following the journey of the unheralded condiment known as “Slawsa”, but your stomach will get queasy reading about everything from industrial chicken plants to the seafood counter at Whole Foods. The writing is masterful.

It’s probably time for a similar book on the convenience store industry. The growth of commercial roadside stores seems to encapsulate all that is right and wrong in our post-industrial society. The bright lights, shiny logos, ice-cold refrigerators, and elaborate coffee kiosks say much about our need for instant gratification, instant calories, and lack of time. Gleaming canopies with antiseptic white LEDs beckon drivers in need of gas for the automobile, but hydrocarbons are merely an appetizer. Fat margins are earned from products that mostly make you fat. What’s your addiction? The gas station can give you a quick fix. Candy, soft-drinks, alcohol, cigarettes, lottery tickets, caffeine and even pizza and brisket can be found in the widening world of convenience. Low-wage employees are surprisingly friendly. Or are those nervous smiles? Anyone heading through the door could turn out to be packing heat and looking for cash, or a strung out junkie searching for a place to sleep.

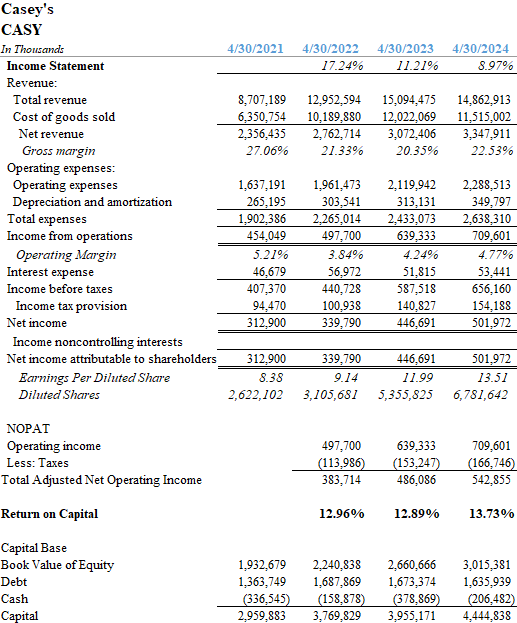

There’s a reason why Buffett fought hard for the Pilot truck stop empire with the Haslam family. The profits are staggering. (Note: a recent article in the Knoxville, Tennessee paper has a wonderful story on the Omaha son who reached the highest levels of business and now runs Pilot.) Have you seen the returns on capital for Casey’s? My, oh, my they are something to behold. When Casey’s bought Buchanan Energy and the associated Bucky’s chain for $580 million in 2020, I thought they were crazy. That’s an amazing amount of coin for 94 retail stores and 79 dealer locations. Guess what? Casey’s barely broke a sweat. Adding pizza to the stores was sheer genius. More margins. Pile ‘em on. My favorite convenience store owner? Alimentation Couche-Tard, the Quebec giant owner of Circle K and Couche-Tard. I just like saying the name. Buying your Zyns from a French depanneur seems tres exotique.

The chart on Casey’s looks like they sell graphics chips. Au contraire. Just potato chips.

Casey’s is a $13 billion market cap company trading at nearly 28 times earnings. The stock is not cheap. CASY is the third biggest chain now with over 2,500 stores in 16 states. Adding $5 billion of market cap to a convenience store business in eight months seems a little excessive to me, but hey, when the stock market trades on vibes… you get Fireballs. Casey’s is based in the Des Moines suburb of Ankeny. Iowa is also home to the headquarters of Kum & Go (another store name that people love to say for some reason).

Not all parts of the automobile service world are going up and to the right like French pole-vaulter Anthony Ammirati. Take car washes. Somehow Omaha managed to go for thirty years with a bunch of sad little spinning brush machines at the back of gas stations. These soapy muppet tunnels were augmented by about three full-service “touchless” emporiums that faced varying degrees of near-insolvency. The VIP at 90th and Center wasn’t just a lounge back then, kids.

Now in 2024, there are car washes everywhere! Apparently, we’ve had it wrong for 30 years. Our cars have been in desperate need of more washing! Or at least that’s what the guys in private equity thought. Sign people up for a subscription model to get a car wash whenever they want in a gleaming new facility and your total addressable market is every car owner in existence. If I see one dirty car in Omaha from now on, well that’s just a damn shame. There’s no excuse. You want a car wash? The choices are endless.

I’m going to go out on a limb here with this prediction. There will be a lot of car washes for sale in about three years. Oh sure, some will be fabulous businesses. Dropping by Menards? Get a car wash. Stuck on Dodge St? Get a car wash. Huge amounts of fixed capital investments, low labor costs, a subscription model. Ka-ching. In fairness, the average age of a car is 12.6 years, so there is something to be said for people wishing to preserve their principal mode of transportation.

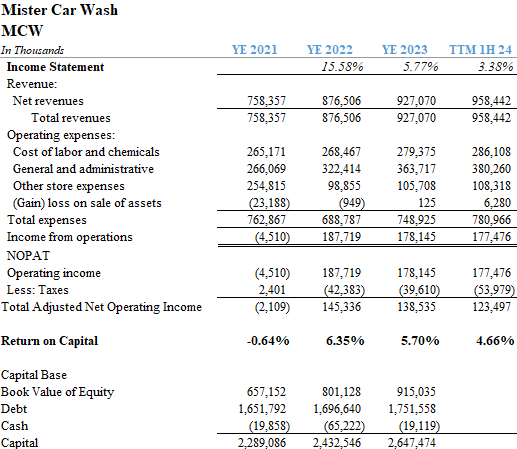

Well, if there’s one thing private equity is good at it’s finding a business model and beating the absolute sh*t out of it. Yes, there’s that competition problem: a lot of people with infinite amounts of cheap capital had the same idea. At the same time. Plus, did I mention huge fixed capital costs? That operating leverage cuts both ways. When volumes aren’t there, the losses pile up quickly – especially when there’s a lot of debt (and debt masquerading as leases). Oh, and the nice equipment requires expensive chemicals, expensive water, and breaks down eventually. So, you can see the risks. The only publicly traded car wash company, courtesy of an escape act from Leonard Green & Partners, is Mister Car Wash.

Despite the stock collapsing from an IPO debut of $20 per share in 2021, MCW still trades at a market capitalization of $2.43 billion. The company has $1.8 billion of debt and operating leases. Sales grew at a lackluster 5.77% in 2023 at the Tucson-based company, and operating income for the first six months of 2024 is basically flat compared with 2023, at $97.5 million.

The problem with Mister Car Wash is very apparent: It simply is not improving returns on capital and economies of scale. More locations in a saturated market are not a recipe for shareholder value creation. Should a car wash chain be selling at more than fifteen times EBITDA? Probably not.