Mauna Loa is Earth’s largest active volcano. The Hawaiian mountain is also the world’s tallest. Mauna Loa rises 30,085 feet from base to summit which is higher than Mount Everest measured from sea level to peak (29,029 feet). To say that much lies below the surface is an understatement. The weight of millions of years of volcanic eruptions has actually caused the Earth’s crust to sink by five miles. Therefore, the total height of Mauna Loa from the start of its eruptive history is an astounding 56,000 feet.

The 45,000 residents of Hilo, Hawaii, while living among some of the most beautiful surroundings in America, also face the possibility of extinction. Mauna Loa last erupted in 2022, but lava flows were minimal. Eruptions damaged small villages in 1926 and 1950. The most recent serious threat occurred in 1984, when massive rivers of molten rock stopped just a short distance from Hilo Bay. The threat to Hilo is not an apocalypse of Pompeian proportions. No, the real danger is a slow and painful demise. If Hilo Bay fills with lava, cargo ships can’t dock. The Big Island would cease to be habitable.

Now if you think I’m about to use my newfound knowledge of volcanic peril as some kind of metaphor for the current state of financial markets, you would be absolutely correct. It’s coming down Fifth Avenue. About as subtle as Captain Kirk wearing a Bill Cosby sweater.

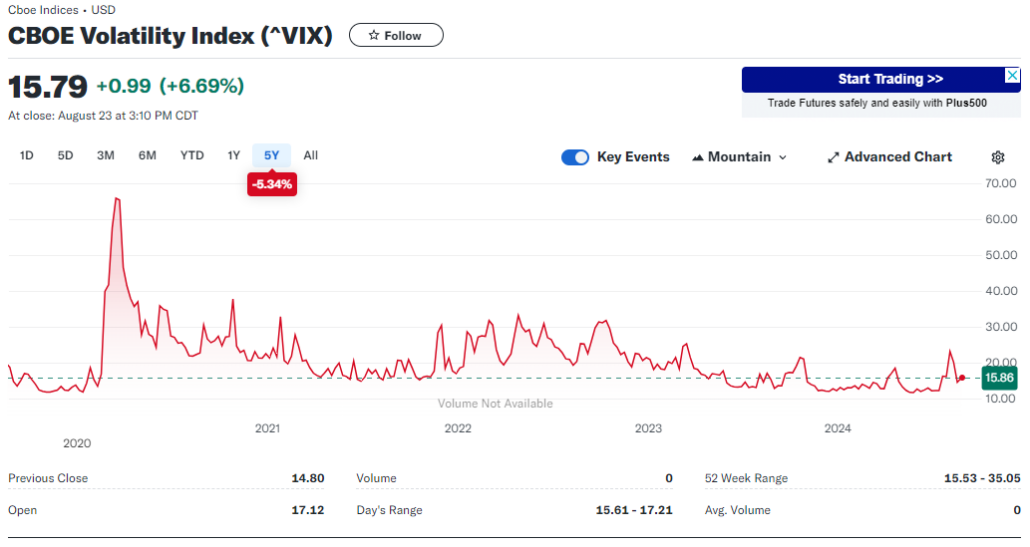

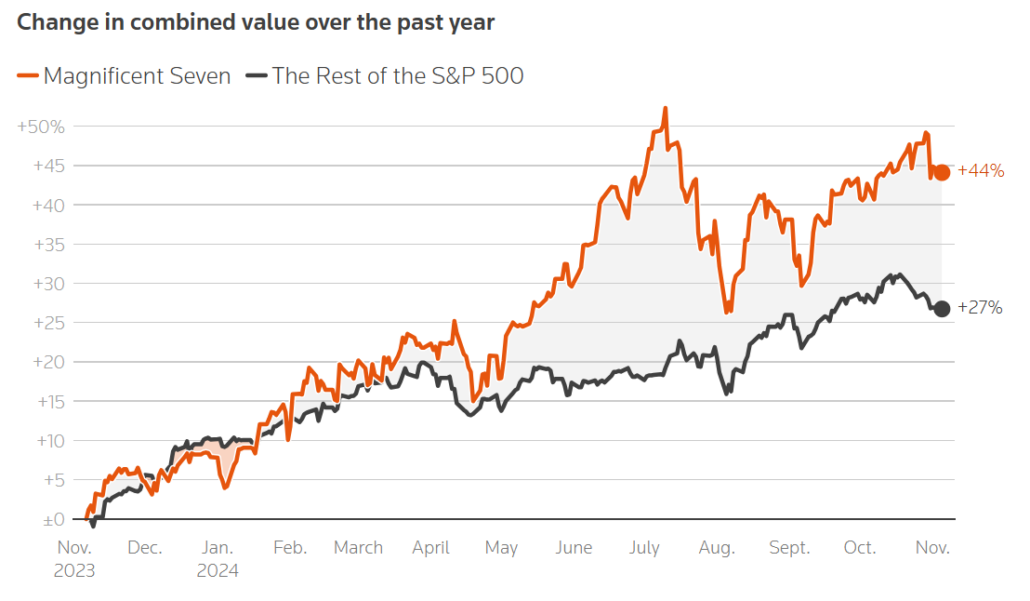

In my metaphor, Warren Buffett is the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. Vast, deep, and refreshingly cool with about $325 billion of cash on hand after selling more Apple stock, according to Saturday’s 3rd quarter report. Yes, he’s got some risk from storms but mostly it’s smooth sailing. Mauna Loa is the AI bubble. As lava keeps building up, the peak gets higher. It’s thrilling… and dangerous.

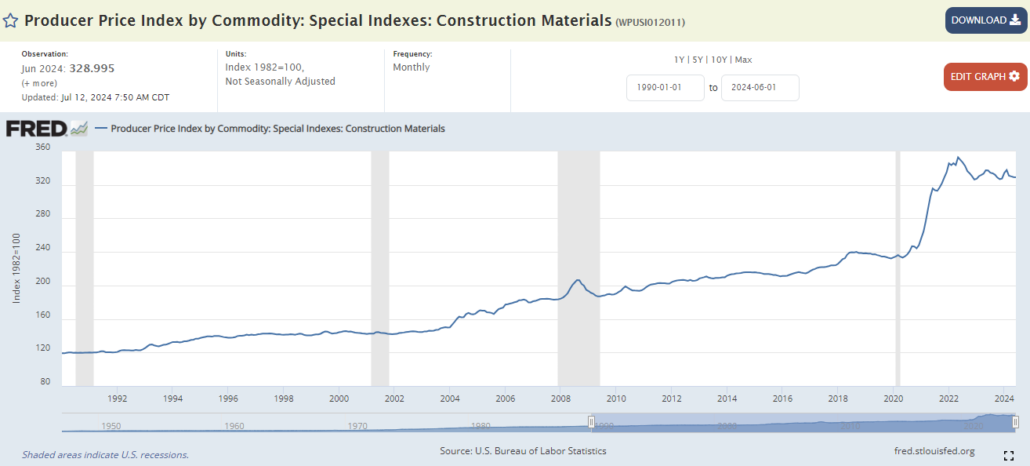

Technology companies will spend $200 billion this year on capital improvements related to artificial intelligence. This technology will require the addition of 14 gigawatts of additional power by 2030. To put that in perspective, Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s coal plant in Council Bluffs produces 1,600 megawatts of electricity.

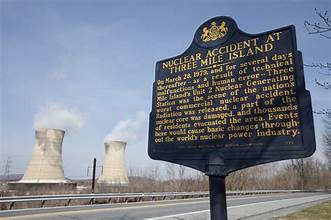

Do you think nuclear is the solution? Well, Georgia just opened our country’s latest nuclear facility. The Alvin W. Vogtle Electrical Generating Plant sits along the Savannah River in Waynesboro. This marvel took 15 years to build and cost a mere $35 billion. Its generating capacity is 4,500 megawatts.

Technology has a history of delivering miracles, but it also bears witness to a poor track record of capital allocation. Look no further than Lumen Technologies (LUMN), the offspring of the fiber optic cable bubble of 1999-2001. Lumen holds the fiber assets of CenturyLink, Qwest and Level 3. If those names sound familiar, there was nothing like the Level 3 bubble for Omahans of a certain vintage who rode the Kiewit spinoff to dizzying heights and painful lows. And we all remember the Qwest Center. Despite a debt restructuring earlier this year, LUMN remains safely in junk territory and will be fortunate to stave off bankruptcy.

You didn’t come here for macro-economic observations or a mini-course in geography. There’s investment ideas to be had.

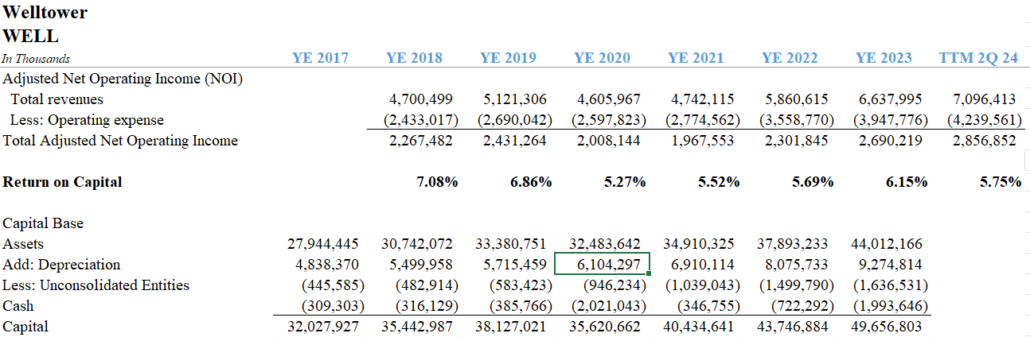

Welltower

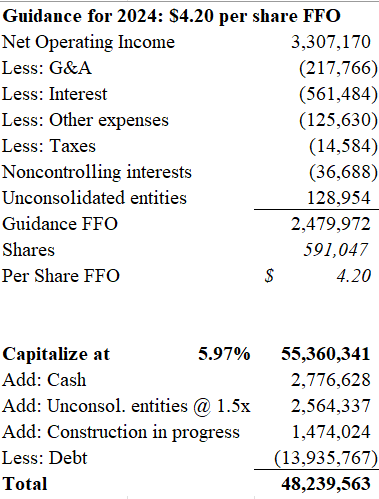

My contention that Welltower remains 40% overpriced relative to the underlying value of its assets took a step back after the company raised annual per share FFO guidance to $4.33 from $4.20. In my estimation, this upgraded forecast is worth $1.3 billion of additional net asset value and raises the total to $50 billion. A nice boost, indeed. Shares rose accordingly.

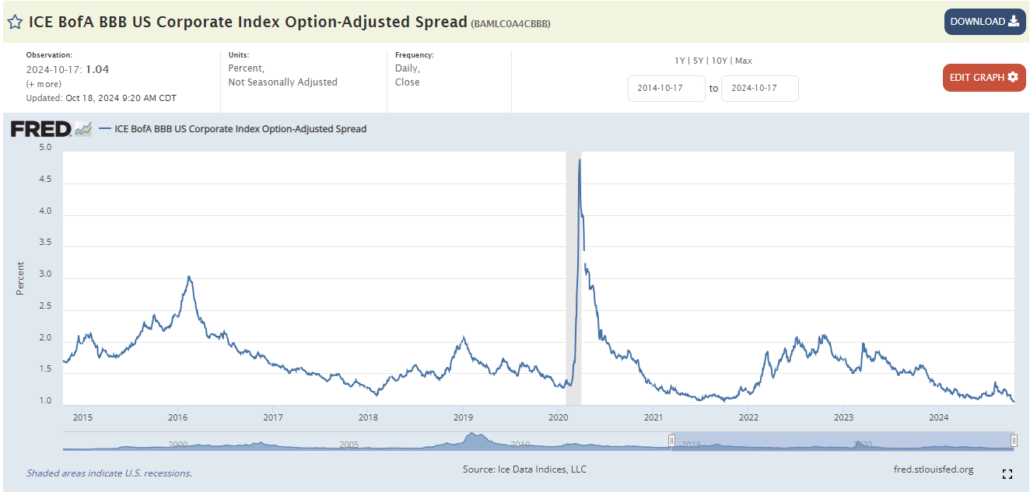

Despite the improved performance, my bearish outlook for Welltower remains firmly intact. If you’re scoring at home, you’ve got a REIT with a market cap of $80 billion yielding less than 2% and trading at 30 times FFO. The company also announced a $5 billion equity offering. REITs like Welltower that invest capital at modest yields are forced to turn to equity for growth when the debt gets too expensive. They become dilution machines.

CK Hutchison

There are times when value traps are like a Siren’s song. It’s like watching Lethal Weapon when nothing else is on. You know that there is no plausible reason why Gary Busey’s henchmen can’t kill Danny Glover in the middle of the desert, but you’re damn well going to watch anyway because you need proof that this cinematic muddle was deserving of three sequels. But thank God they kept going! Lethal Weapon 2 has that fantastic moment when Joe Pesci brings Danny Glover to the South African consulate and tells them he wants to emigrate to the land of Apartheid.

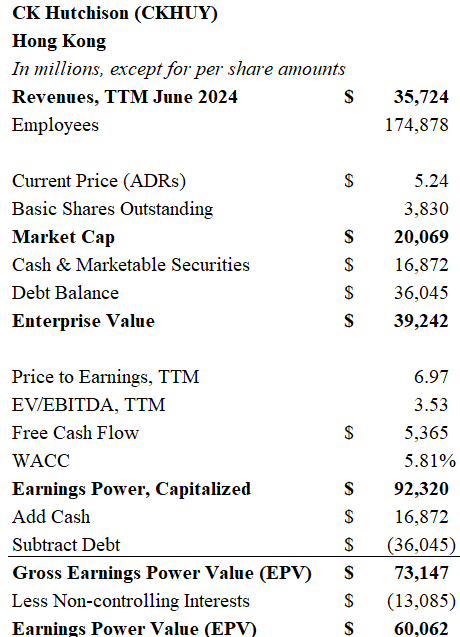

Anyway, CK Hutchison is the descendant of the Hutchison Whampoa conglomerate built over decades by Li Ka-Shing in Hong Kong. I wish there was an updated biography of Li who is now in his mid-nineties and has passed the reigns to his son. He certainly belongs in the business hall of fame. CK Hutchison has a market capitalization of about $20 billion and holds some of the world’s largest port infrastructure assets and telecom businesses. The stock trades at 29% of book value and offers a dividend yield of about 6%.

I ran a few back of the envelope numbers, and CK Hutchison pencils to roughly $60 billion of value. Yet, the stock has been “cheap” for many years. Why decide to invest now? It seems like the second generation of Li’s family (now in their 60’s) has figured out that something needs to be done for long-suffering investors. The company listed its infrastructure assets on the London exchange in August as “CK Infrastructure”. They have also contributed their European mobile networks to a joint venture with Vodafone.

The appeal of CK Hutchison is that its port infrastructure is irreplaceable. Unlike auto manufacturers and steel companies which deservedly trade below book value due to brutal competition, ports are generally impervious to competition. Nature only created so many locations around the globe where massive cargoes can dock. Globalization may be taking a step back, but it’s not stopping. I’m going to dig more deeply into CK Hutchison.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.