There was a hilarious video making the rounds on social media last week that featured a pigeon strutting around a barnyard with a puffed up chest and its head cocked high in the air. The pigeon was imitating a flock of brown chickens who were parading about, pecking at the seeds on the ground. I did what anyone would do when presented with such fantastic barnyard comedy: I pressed the screen and gave the pigeon a heart sign.

I sought deep meaning in this pigeon strutting about. It must be some kind of zoological phenomenon. Genetic mirroring or telepathy. Do pigeons have ESP? I have little knowledge of the biological world, and much less about the psychology of pigeons, so I gave up this notion. Instead, I decided this pigeon must have something to do with interest rates. A natural conclusion.

I couldn’t help but wonder which bird was better off. The chickens were destined for one of those plastic containers with the transparent lids sitting under heat lamps, but they would end up on someone’s dinner table. A meal for a happy family. A short life, but a useful one. The pigeon seemed free. It could fly off at the first sign of the farmer. But it’s death was certain to be grisly: Picked apart by a marauding hawk or flattened by an onrushing vehicle.

You can delude yourself into believing that your fate is different, but the end result is the same. In the long run, we are all dead. So goes the old economist joke. Interest rates are the great equalizer and the tombstone of many speculators are marked with a percent sign. Rising interest rates don’t care much if you’re a pigeon, chicken, or real estate developer. Yes, it’s one hell of a stretched analogy, but I’m running with it.

If you have borrowed a lot of money (something real estate developers love to do), rising interest rates can foul up (or fowl up) any investment equation. To see why, let’s look at a hypothetical building that generates income from rents. After paying expenses, the owner is left with $1,000,000 per year in net operating income. How does one value such a building? The equation is fairly simple, you take the net operating income and divide it by an interest rate known as the capitalization rate, or “cap rate” for short.

The cap rate is a weighted average cost of capital. It weighs the investor’s desired return on his or her equity invested as well as the borrowing cost of debt. The cost of debt is more than simply the interest rate. It includes a factor for the amortization of principal. The resulting cost of debt is known as an annual constant.

In November of 2016, the 10-Year Treasury Yield stood at 2.15%. Lenders usually price their loans at about 2% above the Treasury (known as the spread). So, in November of 2016, the rate was 4.15%. Once you add on the amortization of principal (let’s use 30 years as the amortization term), the annual constant was 5.90%. What was the hypothetical the cap rate? Assuming the developer sought a 7% return on equity and the equity comprised 25% of total capital, the resulting cap rate was 6.175%. What’s $1,000,000 of annual income worth? $16.2 million. The developer was able to borrow about $12 million and made up the balance of the funding with equity of around $4 million.

Today, the 10-Year stands at 3.24%. The annual constant is 6.63%. Holding the desired return on equity at 7% results in a weighted average cost of capital of 6.72%. Dividing $1,000,000 by this cap rate results in a value of $14.9 million. This is a decline of 8%. The developer borrows $11.1 million and invests equity of $3.7 million. All is well and good. The value declined, the debt declined, and the equity required declined in tandem.

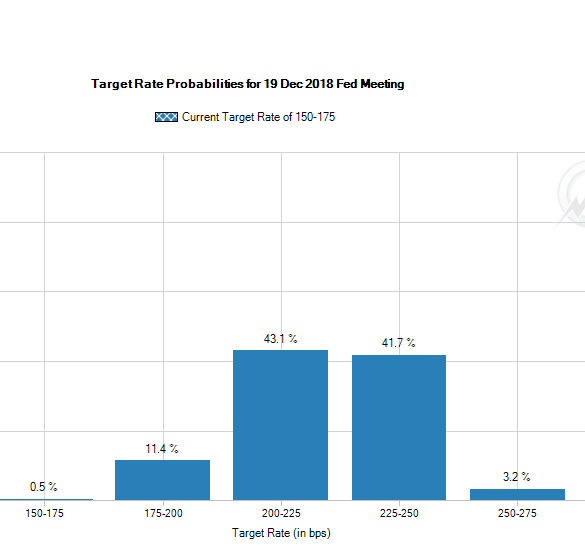

But what happens when the building was built in 2016 and now its time to refinance a construction loan in November of 2018? We said the developer initially put up $4 million for a $16 million building. The debt amount of $12 million made up the difference. Now the building is worth $14.9 million. The bank will only loan $11 million. The developer must make up the difference between the original construction loan and the new permanent loan. An additional $1 million of equity is required – a massive 25% increase.

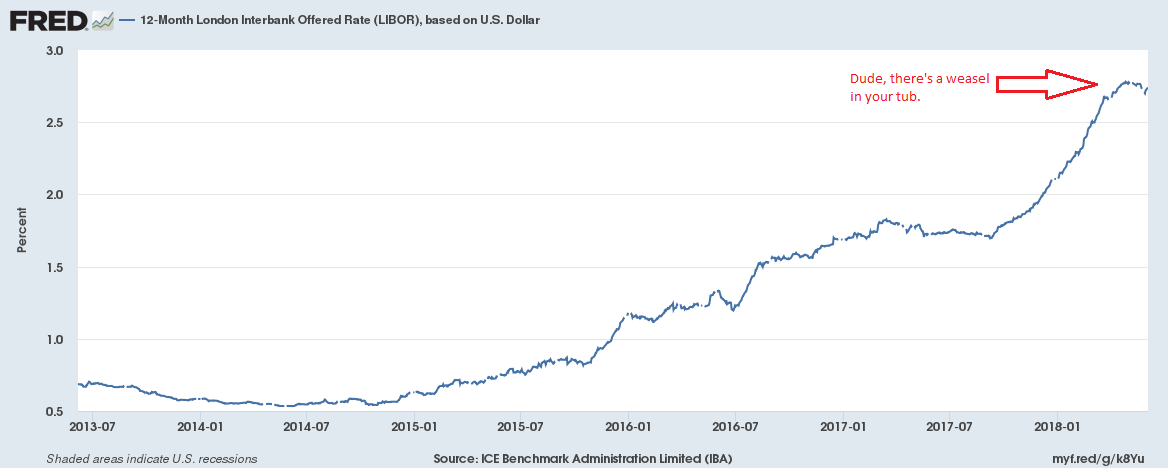

This horrifying situation is already playing out on the global stage. Today’s news brought reports that Chinese developers face $55 billion in debt renewing in 2019. Already Chinese Evergrande, perhaps the world’s biggest developer, witnessed a $1.8 billion bond issue go begging. Fortunately, the majority owner Hui Ka Yan was able to personally put up $1 billion to salvage the deal. Meanwhile Indian developers facing a glut of luxury condominiums have watched short term funding costs surge. Investors have pulled $30 billion out of the money market accounts of non-bank institutions that fund such developments. Indian developers are suddenly in a mad dash for capital.

Pigeon meets hawk. Chicken meets guillotine.