Postive leverage

The Code of Hammurabi dates back to 1750 BC. These ancient laws contained the essence of the first banking contracts for managing loans. The farmer would borrow a bushel of seeds, reap the harvest, give the king about seven bushels of rye and keep three bushels for the family. In the modern parlance of Hammurabi’s descendant Jamiz ur-Dimon, a sound business endeavor earns positive leverage: the return on one’s capital investment should exceed the cost of borrowed money – the rate of interest. What happened if the loan required the farmer to pay back eleven bushels? It would probably end with the removal of a finger or three.

As crazy as things got during the pandemic boom, the basic premise of positive leverage remained intact. Purchases of apartment complexes yielding 4.5% bordered on insanity, but at least lending rates could be found in the 3% range. Now, we have entered a strange, new post-pandemic era. Buyers of apartments have reduced their purchase prices in order to earn a higher rate of return on their capital. Low 5% levels are the reported “capitalization rates” that many buyers are willing to pay. This sounds logical until one realizes that the cost of fixed rate debt today is about 6%. Watch your fingers.

Why would a buyer accept such a meager deal? Three reasons. One, they are willing to earn a return on their own equity that is below the cost of debt. This seems nonsensical. Very liquid low-risk alternatives abound in the form of humble T-bills or, say, Chevron stock with a 4.2% dividend yield. Two, some believe interest rates will decline in the future. There are signs that such joy awaits: The Fed seems poised to reduce rates as inflation slowly approaches the target 2% level.

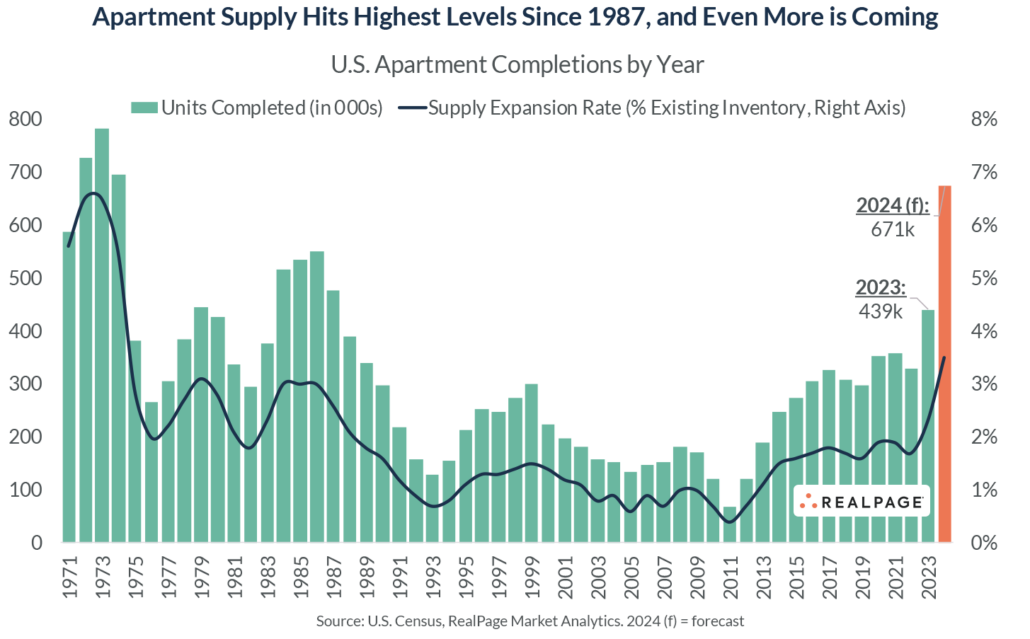

The third reason takes the opposite tack. There is a belief that inflation will lift rents faster than expenses in future years, and negative leverage will pleasantly reverse itself. This theory has merit. The greatest supply of apartments since the 1970’s is about to come to an end. Construction costs and interest rates have risen so high, that most new developments are unfeasible. Home purchases are out of reach for most Americans. The incumbents have a long runway to raise rents once the period of apartment oversupply abates. This is the theory behind KKR’s purchase of Lennar’s multifamily portfolio.

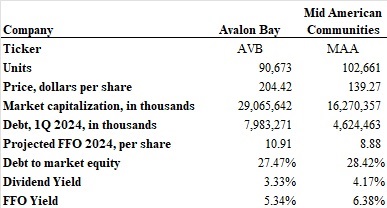

Publicly traded apartment real estate investment trusts (REITs) benefit from a low cost of debt and continue to earn positive leverage. Unlike their private competitors who must grovel for 6% permanent loan rates and 7% construction loan costs, the REITs have healthy balance sheets and can borrow at 5%. Mid-American Apartment Communities (MAA) and AvalonBay (AVB) are two of the largest landlords, and they are projecting returns of 6.5% on their (much reduced) development pipeline.

Both firms locked in low-rate long-term financing during the pandemic. Even as notes mature, healthy balance sheets at MAA and AVB provide pricing power in the bond market. In early January, MAA raised $350 million of debt at 5.1% for ten years – just slightly above a 100 basis point spread to the Treasury note. Assuming their development yields hold to projections and leverage is in the 30% range, they should be able to drive returns on equity to low 7% levels. Not fantastic, but sufficient to sustain dividend yields in the 3%-4% range and grow values in line with the broader economy. Both companies reported record low levels of resident turnover as home purchases have become less affordable.

Not everything is rosy for the REITs. The apartment supply hangover has arrived to pandemic boomtowns like Dallas, Atlanta, Houston and Nashville. Indeed, both MAA and AVB offered some sobering news: rents on newly vacant units were trending negatively in the first quarter. MAA, focused primarily on sunbelt markets, posted a negative 6.5% new lease rate. AVB was closer to negative 0.5%. Fortunately, high resident retention and rent increases of 5% on renewal leases kept the top line growing at both companies. Neither of these stocks is cheap. Taking projected 2024 funds from operations (FFO) – the preferred measure of operating earnings for a publicly-traded REIT – AVB trades at an FFO yield of 5.35% and MAA trades at a 6.43% forward FFO yield.

Meanwhile Farmland Partners (FPI) presents the perils of negative leverage. FPI owns and manages farms (177,000 acres) and has a market capitalization of $553 million. FPI shares peaked at $15 in 2022 and sit at $11.50 today. The dividend yield is a paltry 2.09%. Corn prices have round-tripped during the past five years from $4 per bushel in 2019 to $8 per bushel in 2021, and back to around $4.25 today. Not even Russia’s invasion of one of the world’s top grain-producing nations was enough to sustain wheat prices much higher than $6 per bushel.

Given these daunting agricultural prices, FPI doesn’t offer shareholders much value. The company generated $57.5 million in revenues in 2023 and had $31.3 million of EBITDA. The company spent about $25.6 million on interest and divdends to preferred shareholders, leaving just $5.7 million for common shareholders. This diminutive profit is not sufficient to cover the common shareholder dividends of $12.2 million.

FPI has been selling land to cover its dividend, and really, this is probably the best path forward – sell assets, reduce debt and retrench for the future. The floor on the stock is probably the market value of the land. A swag number of $6,000 per acre means there may be well over $1 billion of land vs $480 million of debt and preferred stock.

Positive leverage feeds your family. Negative leverage only feeds the king.