Old dollars

Rocco Schiavone is a chain-smoking police investigator who has been banished to the Valle D’aosta in the Italian Alps in the humorous and dark cop drama that bears his name. Early in the series, Rocco introduces us to his version of Dante’s hell. Murder is a “level 10 pain-in-the-ass”. Dealing with magistrates is at level 8. A closed tobacco shop is level 9. If Rocco owned apartment buildings, he’d probably list capital improvements on old buildings as a level 7.

We own and operate a collection of older buildings that were constructed in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Let me tell you something. They eat money. Sh*t breaks all the time. Literally. Air conditioners, pavement, carpets, decks, windows, appliances. Depreciation is real, my friends. Yes, it’s a lovely tax-deductible non-cash expense in the early days when a property is new. But as the depreciation wanes, you find yourself replacing capital items at a cost well in excess of the tax benefits.

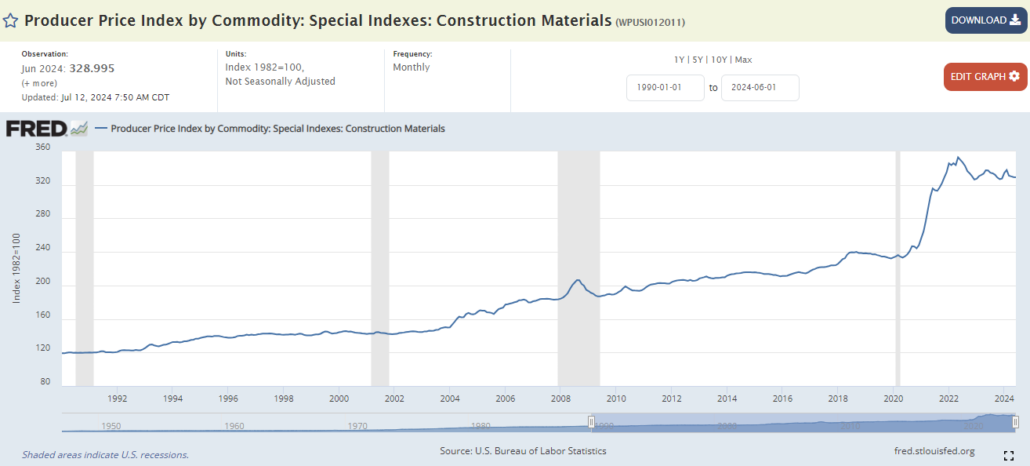

This is the problem of old dollars. It’s even worse in an inflationary environment. If you have a parking lot that was built in 1990 for $20,000, you’ve got zero depreciation benefits today. It’s over. Now you need to replace the pavement. Guess what? It costs $35,000. The greatest inflation in 40 years in the pandemic boom made this problem so much worse. About $10,000 of that parking lot cost increase occurred in the span of four years. Four years! Maybe Rocco would elevate this to a 9.

Buffett lamented the pain of inflation when discussing Berkshire Hathaway’s BNSF railroad. He figured it would cost $500 billion to replicate the railroad today. Depreciation and amortization amounted to $2.5 billion in 2023. In 2024, the railroad announced a $3.9 billion improvement plan. Old dollars vs new dollars. Inflation destroys old dollars. Level 9 agony.

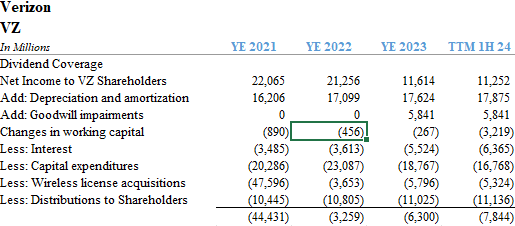

Therefore, a capital-intensive business that is not expending asset replacement dollars at levels significantly ABOVE current depreciation is probably under-investing in the year of our Lord, twenty twenty-four. Take Verizon (VZ). There are only three major wireless carriers in the US. The word “oligopoly” comes to mind. The dividend yield is so tempting at 6.6%. You might think that it’s the sort of holding widows and orphans should cling to for the quarterly stipend. Yet, you would be sorely mistaken.

Verizon doesn’t earn enough to cover it’s dividend when you take into account the immense investment needed to maintain a robust wireless network. Verizon is making capital expenditures that are roughly equivalent to depreciation charges. Four years ago, you might think this was a satisfactory situation. Today? They are behind the curve.

Verizon revenues have been flat for three years at $133 billion. Depreciation on a $307 billion asset base runs to roughly $17 billion per year. The market capitalization for VZ is $168.8 billion and the company has net debt of $148 billion. I think debt-holders will do just fine, but the equity holders will continue a slow grind into obscurity. The company can’t afford it’s hefty dividend of $11 billion per year, and if you account for investments in wireless licenses, the business is cashflow negative.

Defenders may argue that Verizon has been on a costly multi-year 5G network investment path that is about to wind down. I suspect not. If there’s one thing we know about bigger, stronger, faster technology demands, there will be a 6th, 7th and 8th generation waiting in the wings. I’m not even considering the ball-and-chains legacy land line business, pension fund requirements, and the whiff of litigation from aging lead-encased wires from the NYNEX days.

Capital expenditures amounted to $18.8 billion in 2023, so they are running about 7% higher than depreciation. What about inflation? If construction costs are 40% higher in four years and BNSF is spending 40% more, shouldn’t Verizon? The stock’s 30% decline since 2021 reflects a dwindling return on capital. Returns have declined from a healthy 12% in 2021 to just about 7.8% today. Let’s file Verizon in the value trap category. Avoid the siren song of that big dividend.