The richest man in the world pondered the unfinished business of his life. Hoping to mend their rift, Andrew Carnegie penned a letter to his former partner. He requested a meeting with Henry Clay Frick, whose towering palace loomed only blocks away from Carnegie’s own Fifth Avenue mansion. The irascible Frick was in no mood to satisfy the old man’s ego. He received the hand-delivered note, wadded the paper and tossed it back to the messenger. “Yes, you can tell Carnegie I’ll meet him. Tell him I’ll see him in Hell, where we are both going.”

Steel is an alloy forged by fire from iron and carbon. Nothing generated more heat and pure carbon than the coking coal of Western Pennsylvania, and nobody made more coke than Henry Clay Frick. Their business alliance provided Carnegie Steel with a ready supply of inexpensive coking coal. Steel from Carnegie’s Pittsburgh empire would form the backbone of America’s industrial revolution.

Carnegie so greatly admired Frick’s relentless pursuit of cost reductions that he proposed that the coke baron should become the boss of his steel business. Carnegie awarded Frick shares in the company. Frick could be tyrannical, but his methods proved successful. Carnegie Steel’s production and profits soared.

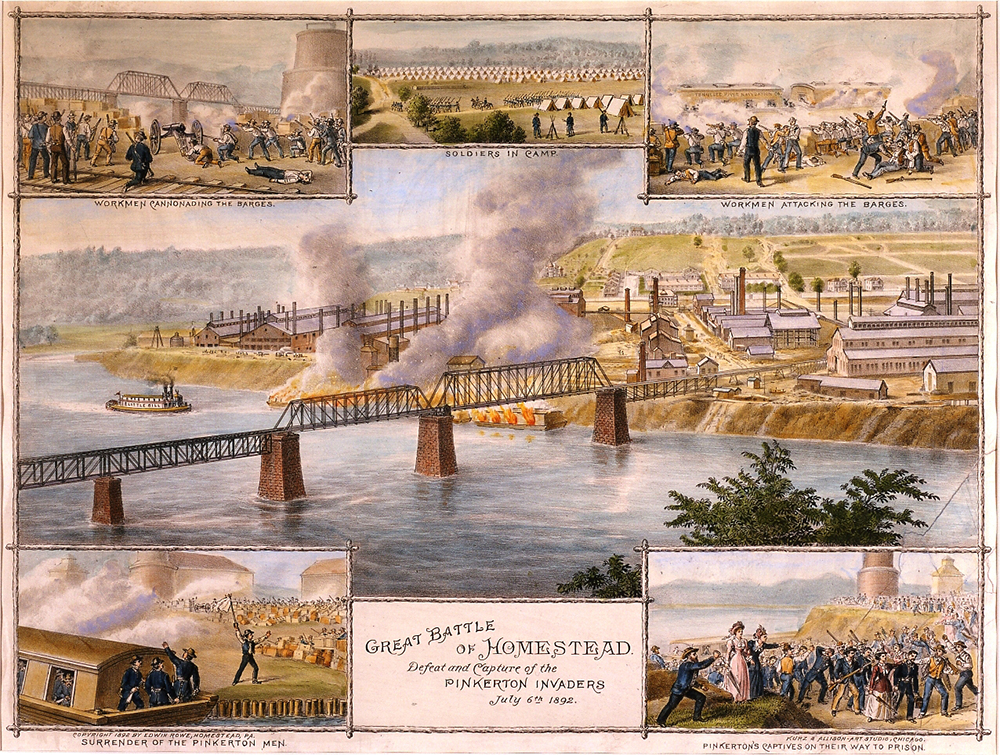

But relations between the two industrial titans became testy. Frick’s involvement in the dam failure that caused the catastrophic Johnstown Flood of 1889 killing more than 2,000 set Carnegie on edge. His violent repression of the 1892 Homestead strike tarnished Carnegie’s reputation. They argued endlessly over the price increases for Frick’s coke. Finally, Carnegie invoked the “Iron Clad Agreement”, a long-dormant business clause which provided a mechanism for a partner’s removal from the business. By January of 1900, Frick was out.

Iron has always been synonymous with strength. Herman Knaust chose the name Iron Mountain for his record-storage business in upstate New York during the 1950’s. As corporations produced millions of paper documents, their safe preservation became paramount. Knaust saw the need to store them in a secure facility where they could not be damaged by fire, theft, or even atomic blasts.

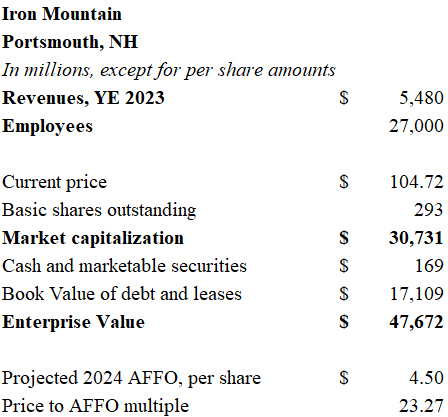

Iron Mountain (IRM) has grown to become one of the world’s leading document and data storage companies with over $6 billion in revenues over the trailing twelve month reporting period ending September 2024 (TTM3Q). Storage generates 62% of revenues, and the remainder comes from services, including document processing as well as the de-commissioning and disposal of used IT equipment. Despite the high concentration of service revenue, Iron Mountain trades as a real estate investment trust. The company has over 7,400 facilities in 60 countries, with 98 million square feet of floor space and 731.5 cubic feet of storage volume.

The main attraction for Iron Mountain during the past four years, and its most likely source of growth for many years ahead, is the construction and operation of data storage facilities. These are the buildings that house IT servers and cloud storage infrastructure. The demands for robust computing power for artificial intelligence has set off a race to develop data centers. Iron Mountain aims to be at the leading edge of the AI infrastructure boom.

The current data center portfolio has 26 locations with 918 megawatts of storage capacity. 327 megawatts is leased or under contract, 184 megawatts is pre-leased, leaving 357 megawatts yet to be leased. The company expects 130 megawatts to be leased for the year 2024. At the end of 2023, Iron Mountain had $1.6 billion of development in progress.

Data center construction requires immense amounts of capital. Cushman and Wakefield, a leading real estate advisory and brokerage firm, recently released a 2025 Data Center Development Cost Guide. The average cost to develop one megawatt of “critical load” (building and IT equipment) averaged $11.7 million in the US. In other words, the cost to double Iron Mountain’s data center capacity would be $10.7 billion.

It will be difficult for Iron Mountain to grow its data center portfolio without issuing more stock. The company’s status as a REIT requires it to distribute most of its income, so retained earnings are minimal. Operating cash flow over the TTM3Q summed to $836 million, and $769 million was paid to shareholders.

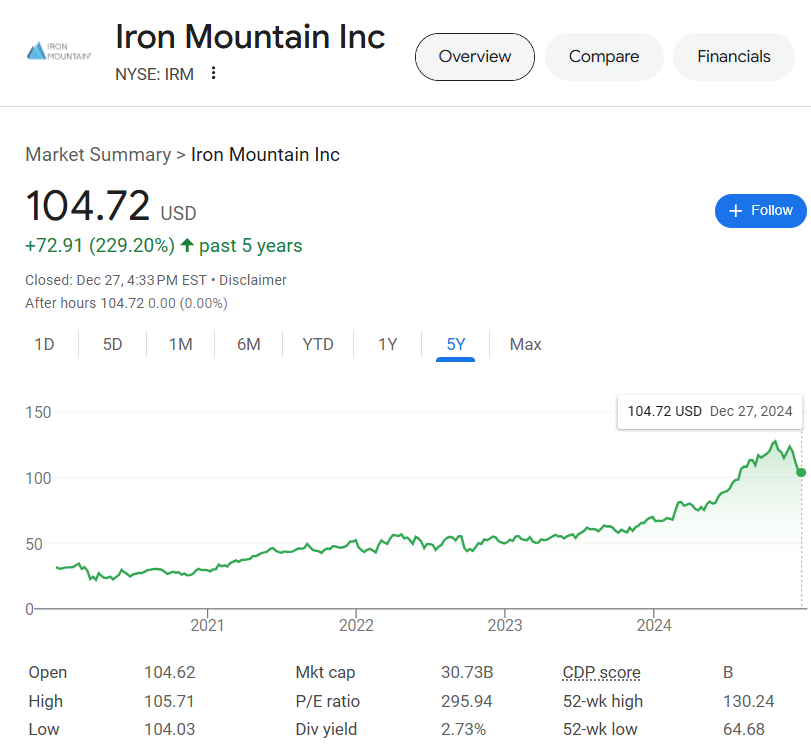

Iron Mountain equity trades at a market capitalization of $31 billion and debt and leases account for $17.1 billion, giving the enterprise a value of $48 billion. The company is rated below investment grade by Standard and Poor’s at the BB- level. The current weighted average cost of the company’s debt is 5.67%, but additional debt in today’s current rate environment would cost IRM 6.7%. Additional leverage is not a prudent source of capital unless it is paired with the issuance of new stock.

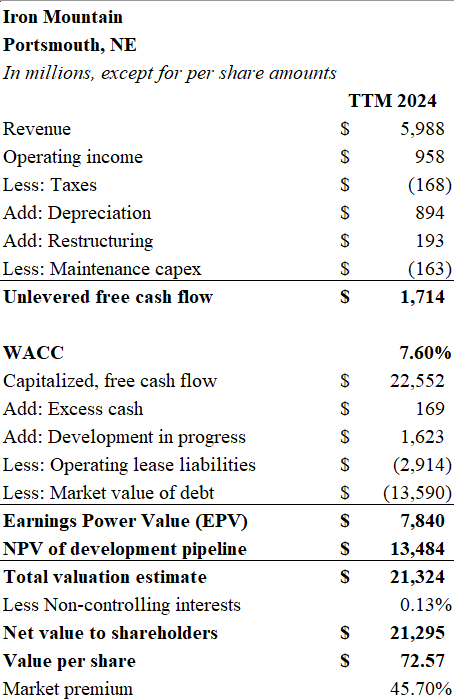

At today’s market price of $105.73 per share, Iron Mountain trades at a 45% premium to its intrinsic value.

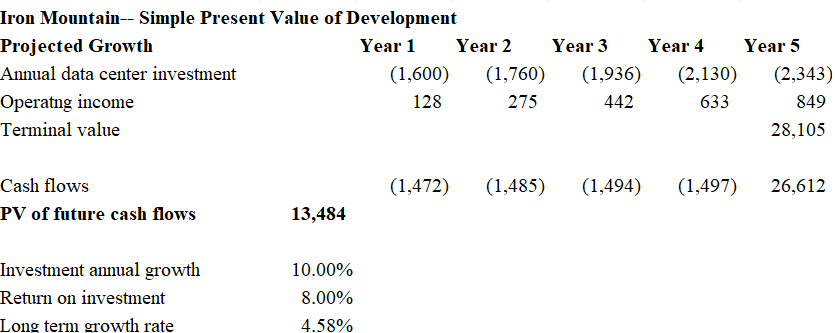

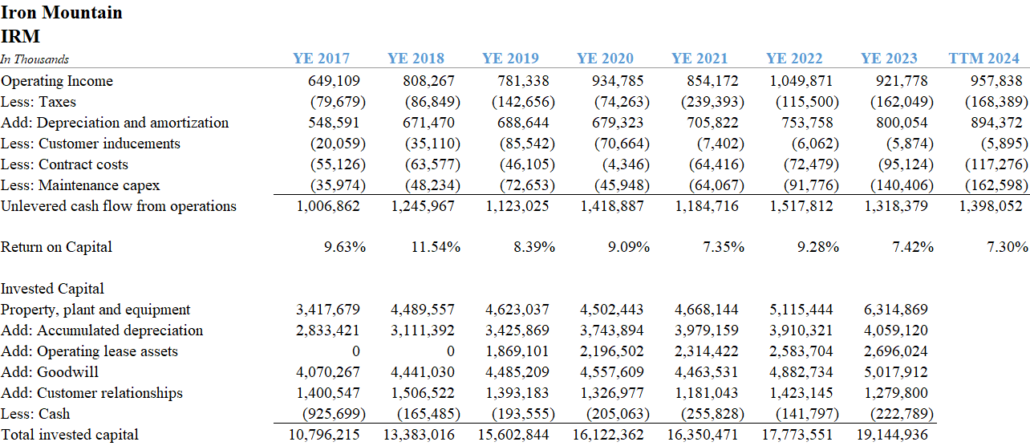

I’ve taken a two-step approach to arrive at a value of Iron Mountain’s equity closer to $73 per share. Using the earnings power valuation (EPV) method, I took the free cash flow for the business and discounted it at the weighted average cost of capital of 7.6%. The aforementioned 6.7% cost of debt (5.53% after taxes) account for 34.8% of capital, and 8.7% was used as the cost of equity. I simply priced equity 2% over the market cost of debt. Unlevered free cash flow of $1.7 billion capitalized at 7.6% is $22.5 billion. Subtract the market value of debt and leases ($13.59 billion and $2.91 billion, respectively), and the net EPV is $7.84 biilion.

Next, I went fishing for the simplest possible explanation for the gap between the market value of the business and the intrinsic value of its current assets – the unknown future development pipeline. I created the most basic discounted cash flow projection possible. I assumed that IRM placed a development pipeline into service that started with $1.6 billion in Year 1 and grows by 10% annually over five years. I assumed the data centers earn an 8% yield on cost. The terminal value of the business reflects perpetual growth at the current Treasury 10-year yield. The present value of future cash flows, discounted at 7.6% amounts to $13.5 billion. The net value of these two figures, after adjusting for noncontrolling interests is $21.3 billion, or $72.57 per share.

Readers may say that my discount rate is too high. After all, institutional quality real estate continues to trade at capitalization rates between 5% and 6%. I would argue against a lower discount rate for two reasons: One, the faster that the world embraces digital data, the more IRM’s legacy businesses of document processing, storage and destruction diminishes in value. Two, the discounted cash flow model, while laughably over-simplistic, is also generous. Few institutional real estate developers earn much more than a 6% yield on their costs in the current environment. More importantly, my model makes no allowance for the rapid depreciation of the equipment and possible obsolescence of the facilities as more sophisticated ones are built.

Frankly, my earnings power valuation is also quite generous. I add back restructuring charges, despite their seemingly recurrent nature. The company has incurred nearly $670 million in restructuring charges since 2019. I make a deduction for the ongoing capital needs for the facilities, but no deduction is made to unlevered free cash flow for the “customer inducements” and “contract costs” that exceed $100 million annually. These charges appear among capital items rather than on the income statement where they probably belong.

More conventional metrics also point to Iron Mountain’s inflated valuation. The company offers a 2.7% dividend yield – thin gruel in a market where 10-year TIPS can be bought with a 2.23% handle. Meanwhile, IRM trades at 23.5 times adjusted funds from operations (AFFO) projected to be $4.50 per share for 2024.

Iron Mountain will be forced to raise equity in large amounts to fund the data center program. The additional shares will be highly dilutive if the investments can’t yield more than the cost of capital.

Iron, carbon, steel, silicon…the future beckons.

Until next time.

Note: Meet You in Hell is an entertaining book by Les Standiford, published in 2005, that chronicles the formation and dissolution of the relationship between Carnegie and Frick. Chapter One colorfully describes the “letter incident”.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

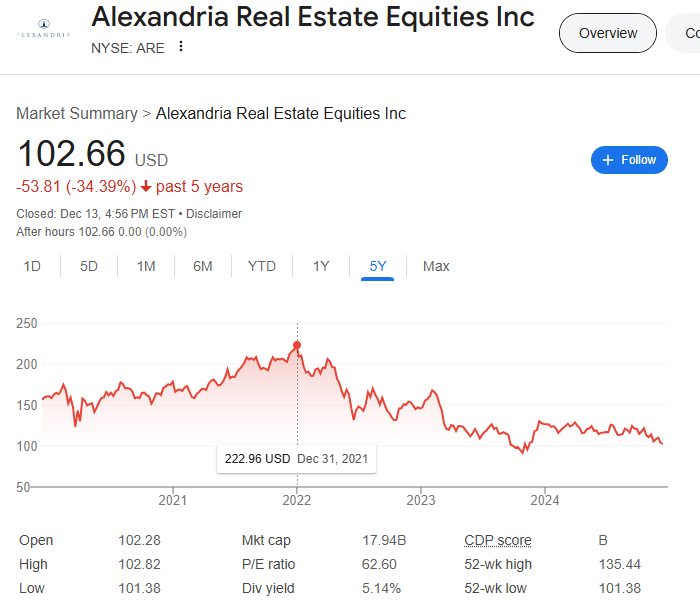

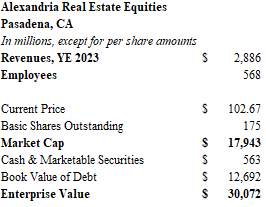

Alexandria Real Estate Equities is the leading landlord for the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. The Pasadena-based firm boasts 41.8 million square feet of office and laboratory space, with a further 5.3 million square feet under construction. Shares of the real estate investment trust with the ticker ARE closed at $102.66 on Friday. Total market capitalization of $18 billion represents a slight discount to the book value of equity on the balance sheet.

Alexandria focuses on campus “clusters” where it has been proven that the proximity of multiple science innovators stimulates creativity. These clusters have been developed in locations with robust university ecosystems such as Boston, the Bay Area, San Diego, New York, the DC metro, Seattle, and the “Research Triangle” of North Carolina. Most recently, the company announced a 260,000 square foot lease with the bacterial disease biotech firm Vaxcyte at the San Carlos, CA campus.

Occupancy is a healthy 94.7% across the portfolio. Alexandria’s balance sheet shows $33 billion of real estate assets (undepreciated) and $12 billion of debt. Standard & Poor’s regards the debt as investment grade with a BBB+ rating.

Despite the good metrics, Alexandria stock has been pummeled over the past three years, falling by more than half from the $223 peak at the end of 2021. The biotech industry boomed during the early stages of the pandemic, but the subsequent collapse has been brutal. Deals in the pharmaceutical industry have fallen to their lowest level in a decade. This is a far cry from the halcyon days of 2020 and 2021, when over 183 firms raised more than $30 billion from initial public offerings. Today, most trade below their IPO price, and many are cash-burning zombies.

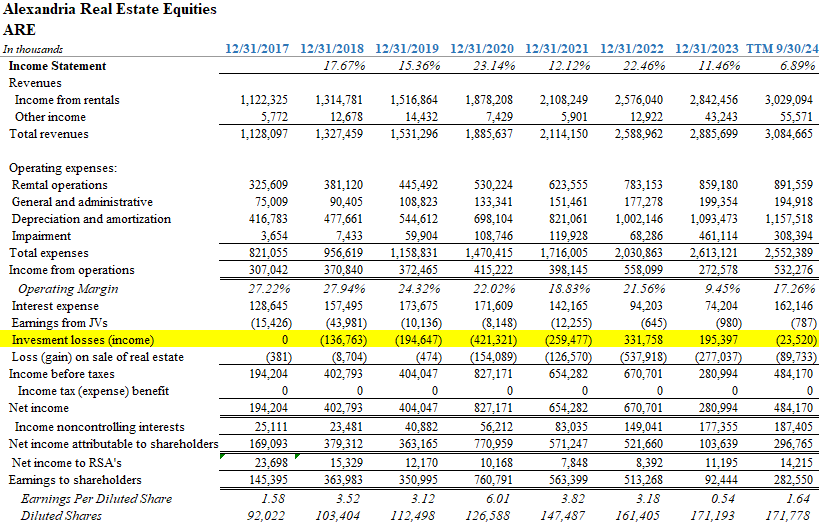

Over the years, Alexandria has invested in many of its tenants with it’s own venture capital arm. Between 2018 and 2021, Alexandria booked over $1 billion in investment gains on its portfolio.

Unfortunately, as the market turned hostile, investment losses in 2022 and 2023 exceeded $527 million. At the end of September. Alexandria carried $1.5 billion of investments among its assets. Some are publicly-traded and marked-to-market on a consistent basis, but most are illiquid and the value is highly subjective.

Trouble in the biotech industry also led to losses of rental income. Between 2020 and 2023, ARE faced lease impairments in excess of $750 million.

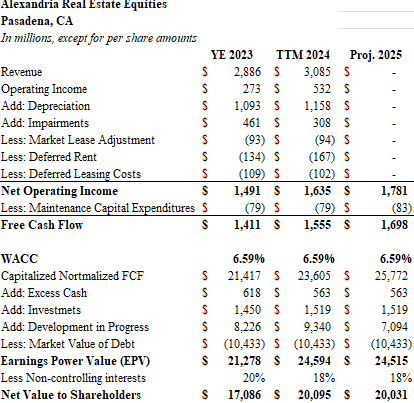

Is Alexandria’s stock now a bargain? Not quite. I consider a stock trading 25% or more below its intrinsic value to signal an investment green light. Based on my calculations, the stock trades at a 7% discount to the value of its underlying assets.

Intrinsic value calculation:

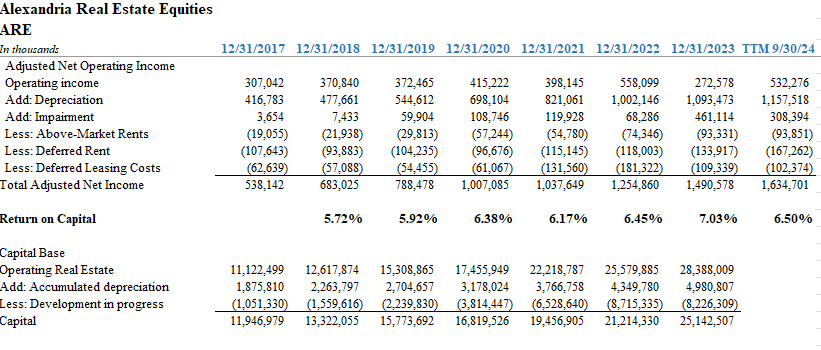

By my estimates, 2025 free cash flow will be approximately $1.7 billion. Capitalizing this amount at 6.59% leads to a value of $25.7 billion for the operating real estate. Adding development in progress and the company’s investment portfolio, both at book value, leads to a total asset value of $34.9 billion. Subtracting the market value of debt results in a net value of $24.5 billion. Many of the company’s assets are held in joint ventures with developers, so about 18% of the value is attributable to these partners, leaving a net asset value of $20 billion.

There are some important caveats to consider:

- I’ve mentioned the risky nature of the venture-backed tenants. They sow the seeds of major upside for Alexandria, but they could also prove to be a source of future impairments.

- Interest expense is mostly capitalized. The company reported about $162 million of interest over the trailing twelve months. In reality, this figure is much higher. In 2023, about $364 million of interest was capitalized because it was related to debt on new developments. This is entirely appropriate, but the failure to lease pending space could lead to a drag on results if this interest must be deducted from operating profits

- New developments are significantly more costly. Although ARE is only expanding its portfolio by 13% with its current development pipeline, the cost of new projects equate to more than 28% of undepreciated book real estate assets. Construction costs suffered massive inflation since 2020, and it will be difficult to obtain future rents that need to be 30-40% higher than current market levels to drive adequate returns.

- Returns on capital have never been much better than 6%. Taking a look at cash operating income as a percentage of undepreciated operating assets shows a company that has earned returns that aren’t exactly eye-popping. This is institutional-quality real estate with very low debt costs, so the 6% neighborhood may be respectable, but its not the kind of number that will drive exceptional growth.

Which brings me to my final issue with all REITs in an environment of sustained higher interest rates: the prospect of equity dilution.

REITs, by virtue of their tax-exempt status, must distribute most of their profits. Retained earnings are a limited source of growth capital. External capital and the reinvestment of gains from property sales provide the funding for growth. In the low-rate era between 2009 and 2021, earning a 6.5% return on capital drove returns on equity to the low double digits when borrowing costs were in the 3-4% range. Indeed, as share count rose by 65% over the past six years, assets on the balance sheet increased by 170%. This positive leverage is the key to building real estate wealth.

In the current rate environment, the math isn’t so hot. If Alexandria finds itself unable to grow with low-cost debt, incremental shares must be offered to the public in ever-increasing quantities. When capital is expensive, REIT shareholders face dilution.

So where does this leave us?

Alexandria has a solid business renting space to big pharma companies. Most of its debt is financed at 3.8% for another 13 years. The stock trades at a slight discount and offers a nice dividend in excess of 5%. However, ARE also relies on the ability of many cash-burning high-risk ventures to continue paying rent.

Many firms will fail. Some may become blockbusters. Alexandria doesn’t have to bet on one horse, it owns the thoroughbred farm. They know which smaller tenants are growing and making progress on their drug pipelines. In fact, their venture business gives the firm upside when a tenant wins the derby.

If you have a favorable outlook on the biotechnology industry, Alexandria shares seem like a decent way to receive a nice dividend while a recovery forms. Indeed, there are signs of a thaw. Several new funds have found traction. Venture money may be flowing to the industry once again.

As for me, I would prefer to wait for a further decline in the share price to make an acquisition. The company has $9.3 billion of development in progress that may struggle to find tenants willing to pay top dollar for lab space. The new paradigm for inflation-adjusted rents has not been “battle-tested” in a market where firms are looking to preserve cash. Splashing out big dollars on fancy office space probably won’t sit well with venture capital investors who have seen much of their pandemic era gains evaporate. Corporate austerity may be the new watchword for the biotech industry.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Louis XIV was a control freak. The “Sun King” reigned from 1643 to 1715. The king’s day was timed to the minute to allow the officers in his service to plan their own work accordingly. From morning to evening his day ran like clockwork, to a schedule that was just as strictly ordered as life in the Court. “With an almanach and a watch, one could, from 300 leagues away, say with accuracy what he was doing”, wrote the Duke of Saint-Simon.

When it came to rigorous discipline, the King’s finance minister was equal to his master. The legendary Jean-Baptiste Colbert brought fiscal responsibility to a kingdom that was nearly bankrupt at the start of the 1650’s. Colbert, a relentless workaholic, introduced a system of government accounting that was the first of its kind. Spending was brought to heel and tax collections were enforced.

Colbert is often credited with laying the foundations of the modern French state. He centralized government power and introduced mercantilist policies which included investments in infrastructure and academies for the sciences, engineering and arts. Colbert raised tariffs on manufactured imports like Venetian glass and Dutch textiles and promoted French industry.

Although modern France recognizes Colbert’s fiscal innovations, few mourned his passing in 1683. The French taxation system was notoriously regressive, with nobles and clergy being exempt. Peasants, laborers and business owners were taxed heavily. Even many noblemen despaired at Colbert’s reforms. Oral testimony was no longer allowed for verification of one’s noble status. The rolls of noblemen were purged as those of the highest caste were required to provide documentary evidence dating back more than 100 years.

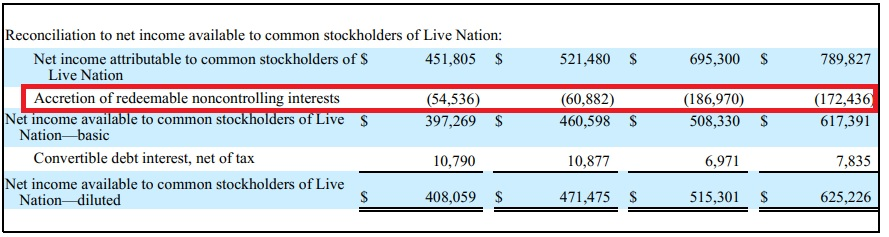

In modern finance, the lack of control can lead to all sorts of complications. Take Live Nation (LYV), for instance. Live Nation owns Ticketmaster and produces over 44,000 live music and events around the world each year. Yet, during the first nine months of 2024, only 60% of earnings were attributed to shareholders. The company owns and operates venues through a series of joint ventures with local promoters and facilities owners. These noncontrolling interests have a claim on 28% of net income.

There are also redeemable noncontrolling interests that have a claim on company earnings. These are opaque arrangements with promoters that have the ability to sell their interests back to the parent company using a put option. The problem with these put options is that their costs are variable in nature – the more the company earns, the larger the option premium gets.

These redeemable noncontrolling interests are shown on the balance sheet as a liability, but because they can increase in value over time, this “accretion” is also deducted from earnings per share. For the nine-month period ending September 30, 2024, earnings amounted to $849.2 million. Subtract the share for noncontrolling interests, and $695.3 million was left. Or was it? Earnings per share should have been $2.95, but the accretion of redeemable noncontrolling interests for the period meant that only $2.18 was attributable to shareholders. This means that LYV is trading at 160 times earnings for the trailing 12-month period.

Live Nation seems to be overvalued by as much as 54% once deductions are made for noncontrolling interests. I am not even factoring in the possibility of anti-trust litigation for monopolizing the ticket industry. While such enforcement seems less likely under the Trump administration, much risk remains.

Live Nation posted $23.3 billion in revenues over the trailing twelve-month period. There are massive margins in tickets. Ticketing accounts for about 12% of revenues, and 37% of operating income. The venue operations, on the other hand, are capital intensive and only generate 5% margins. To make matters worse, growth seems to have peaked. With the conclusion of the Taylor Swift tour and the post-pandemic surge fading from view, revenues declined by over 6% in the third quarter. Aside from the excitement around the Sphere (SPHR) and a few major tours, many concerts have struggled over the past year.

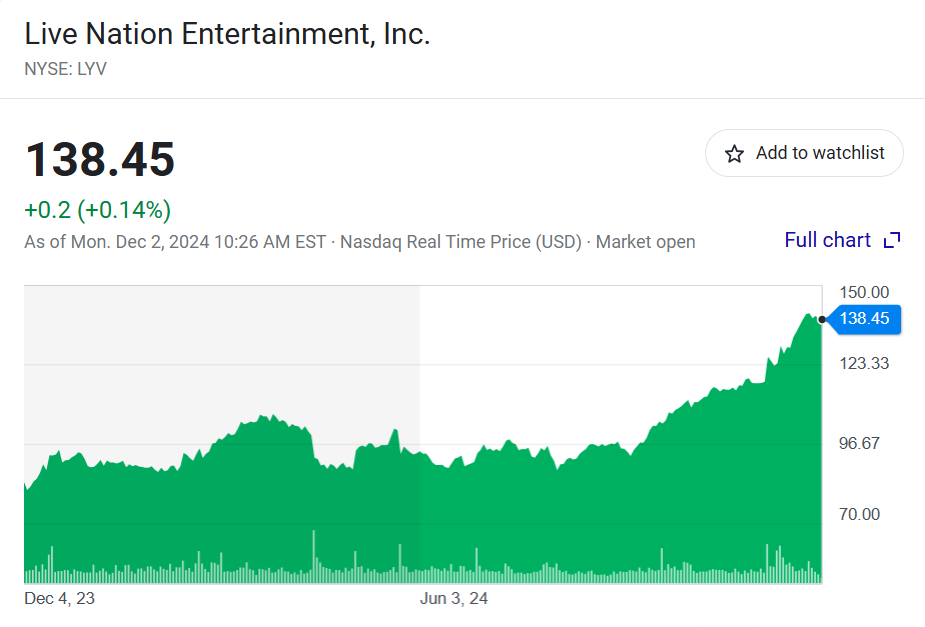

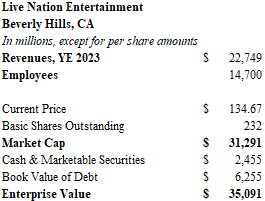

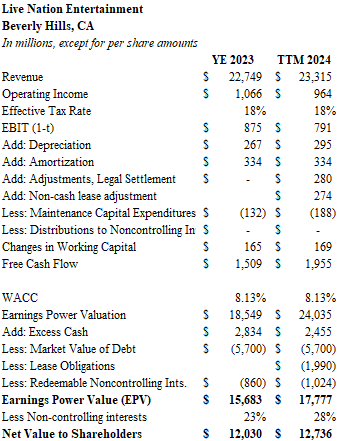

Below is my earnings power valuation for Live Nation. I calculated an equity value of $12.7 billion versus the current market capitalization of $31.3 billion. I applied a weighted average cost of capital of 8.22%. This factor includes $6.3 billion of debt with an S&P rating of BB, or an imputed debt cost of 5.85% under current yields and spreads.

Is my discount rate too high? Perhaps. But even if you use 6%, the equity value sums to $18.8 billion. Should I factor in something for growth? Maybe. But there doesn’t seem to be much near-term growth. In the long-term, growth will come from more venue developments and leases – a business which generates poor yields on capital. There’s a reason why most venues are built with taxpayer funds: the economics rarely work. No amount of U2 and Adele concerts can save The Sphere from an eventual bankruptcy filing.

I am also being pretty fair with how I treat the redeemable noncontrolling interests. I do not deduct anything from earnings. Instead, I have deducted the $1 billion book value shown on the balance sheet after operating income has been capitalized. Finally, I only make a deduction for maintenance capital expenditures of $188 million. In reality, the future capital commitments for the firm are much greater.

It was said that between 3,000 and 10,000 courtiers visited Versailles on a daily basis for a chance to mingle with the Sun King. If only Colbert had Ticketmaster in his day.

Until next time.