MASH was always full of laughs, but those CBS writers never let you forget about the senseless brutality of war. One minute the affable Colonel Henry Blake is on his way back from Korea to his wife and kids, the next minute he’s gone. Radar runs into the triage tent to tell everyone the news. Gut punch.

So goes Hollywood. Blake’s actor, McLean Stevenson, wanted more screen time. Fed up, he asked to be released from his contract in 1975. CBS obliged. I’m sure McLean Stevenson appeared in other roles. I can’t tell you what those were.

We don’t like to admit so much in life comes down to luck. It has to be skill, knowledge, expertise or “God’s plan”, right? There must be an explanation.

But sometimes luck really is the answer. Henry Blake lands in Tokyo. McLean Stevenson gets cast as Mr. Rourke on Fantasy Island.

Sure, you can put yourself into a lucky positions. Sam Zell’s father knew the Nazis were coming for his family. He prepared. He moved assets. He fled Poland. He also just happened to catch the last train out before the Luftwaffe bombed the tracks.

America has had a lot of lucky breaks. In the War of 1812, England was on the verge of reclaiming her colonies. Washington, DC was under siege by the British army. After the White House burned to the ground, a great tornado struck the Potomac valley. The British fled.

But we’ve gone too far. We’ve turned into a nation of degenerate gamblers. It’s not enough to go to a casino down the street or have an online sports betting app on your phone. You can trade memecoins! Just buy stock in quantum computing companies with no viable way to profitability. Or, you can roll your entire net worth into triple-levered Nasadq QQQ ETF’s. You’ll be fine. Stop-loss orders always get filled in a market panic.

That’s why value investing appeals to me. There is so much luck, chance and uncertainty involved in business. You can’t know the future. But you can hope to find companies that are selling at a price with a margin of safety – they appear to have some protection from downside; from bad luck and all of its cousins.

The most unlikely place to find good companies selling for reasonable prices is Hong Kong. As unbelievable as that sentence may read, it was not generated by Co-Pilot. Two weeks ago, I wrote about the bargain price for Johnson Electric (JEHLY), and briefly mentioned Budweiser APAC (BDWBY) and Sinopec Kantons (SPKOY). This week I am recommending WH Group (WHGLY).

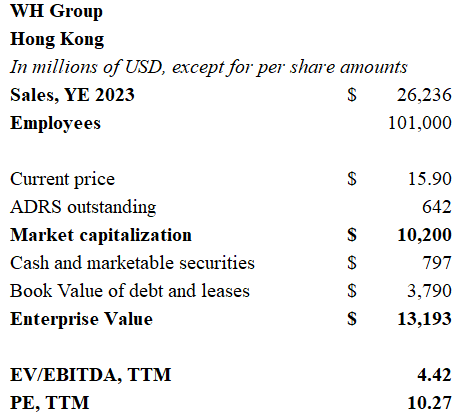

WH Group is the world’s largest producer of pork. The stock trades on the Hong Kong bourse and can also be bought over the counter at about $15.90 per share. The company had revenues of $26.2 billion in 2023 and $25.4 billion over the last twelve months’ reporting period through June of 2024. China and Europe accounted for 39% of WH Group’s 1H2024 revenues, and 46% of operating profits. The company was unfazed by the pandemic, instead it suffered it’s worst financial results during 2023 when pork prices in North America collapsed causing major inventory write-downs at the Smithfield division.

WH Group purchased the Virginia-based Smithfield for $4.7 billion in 2013. Now, WH Group plans to-relist Smithfield in a share offering. The projected value of the Smithfield operation is $10.7 billion. As part of the IPO, WH Group will reap about $540 billion in cash and reduce its ownership stake from 100% to 89.9%.

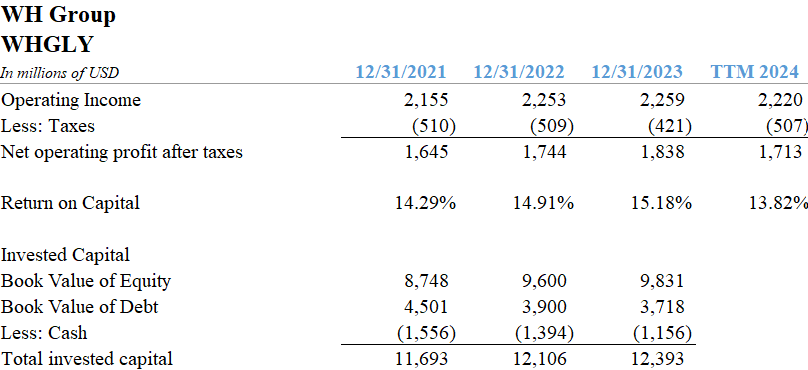

WH Group trades with a trailing PE of 10.4 times earnings and pays a substantial 5.6% dividend yield. The company is rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s, carrying a modest $3.8 billion of debt and operating leases with a weighted average interest rate of 4.4%. Gross margins are in the 19% range, with net margins above 8.5%. Returns on capital have been between 13% and 15% in recent years which seems noteworthy for a food processor.

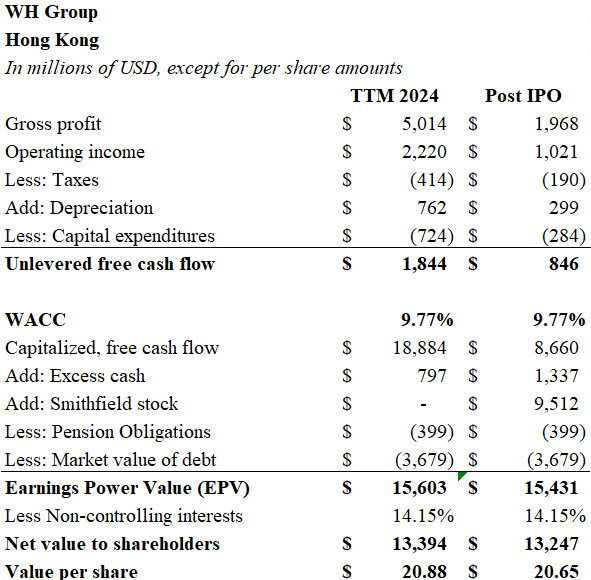

By my calculations, WH Group has more than 23% upside. Unlevered free cash flow for the company exceeded $1.8 billion over the trailing-twelve month reporting period. Employing a weighted average cost of capital of 9.77%, gives WHGLY a value of $18.9 billion. Adding $800 million of cash but subtracting the debt and about $400 million of pension obligations leaves an earnings power valuation of $15.6 billion. Adjusting for non-controlling interests, WH Group is worth about $13.4 billion, or $21 per American share. The effect of the Smithfield IPO is also presented below.

There are plenty of caveats. WH Group is listing its Smithfield operations because they have an opportunity to raise some cash, but the political optics are important. Distancing China from the US food chain is probably a well-caulculated move to insulate the company from US criticism. Second, WH Group has already run up by about 30% over the past 12 months. The really low-hanging fruit has been plucked. Finally, the Chinese economy is suffering a dramatic downturn as the property market hangover sets in. Consumers are in a frugal mood. Eating less pork may be a way for Chinese households to economize.

The Smithfield IPO will be a landmark moment for WH Group. If the North American operations receive a $10.7 billion stamp of approval by American investors, it could lead investors to ascribe a higher multiple to the Chinese and European businesses.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

My sister and I always knew it was a big deal when Dr. Sidney Freedman showed up on MASH. The psychiatrist wasn’t there to join the wise-cracking banter in the triage tent. And he sure wasn’t going to put on dresses with Klinger or pull pranks on Dr. Winchester. Somebody was about to get their psychological puzzle dis-assembled right there on national television.

In the final seasons of the comedy show’s 11-year run, MASH explored some dark territory. Even though MASH was set during the Korean War, just about everyone knew it was really about Vietnam. As the series went into its last few years, CBS seemed to stop pretending. Alan Alda’s hair grew pretty long, and so did his dramatic scenes.

Not only was it ground-breaking to put a psychiatrist on television in the 1970s, the writers gave him the rank of major. Dr. Freedman outranked the surgeons, BJ and Hawkeye. CBS seemed to be asking a generation of Americans burdened by the Vietnam era the ultimate question: What good is fixing a broken body if you can’t heal the soul?

It was actually our mother who clued us in to Dr. Freedman. Mom took a keen interest in Sid, just like she preferred the wit and charm of John Chancellor to the gruff Walter Cronkite. Mom had a master’s degree in social work, so Sid was her kind of people. Yep, when Dr. Sidney Freedman came to the camp, we knew it was time to go deep.

Having a mother with an MSW was like having Dr. Sidney Freedman right in our home. Well, in Mom’s case, it was more like a combination of Sid plus a mixture of Helen Reddy and Maria from Sesame Street. The childhood distress of silent treatments from girls in the classroom, peer pressure, embarrassment about acne – Mom was always ready with the right words. “Maybe they’re being mean because of their own insecurities”. Thanks, Mom!

They could make a modern spin-off of MASH with Dr. Sidney Freedman as the lead character. Only this time he wouldn’t be a shrink in a military hospital unit, he’d be running a private credit firm. Preferably one named for a Greek or Roman god. “Welcome to my office. Make yourself comfortable. Some of my clients sit, but most prefer to lie on the SOFR.” This script practically writes itself. It would be like having Dr. Wendy Rhoades on Billions, only better.

You need to have a degree in psychology to understand today’s markets. The keen ability to diagnose and treat delusional thinking is a prerequisite. Consider this: an electronic token generated by a computer algorithm has reached a price of $100,000. The “currency”, invented by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008, is backed by no government and has few nodes of exchange except for illicit activities. Who is Satoshi Nakamoto? To quote Nate Bargatze, “Nobody knows.”

Let’s take it a step further. There is a company called MicroStrategy (MSTR). It is nominally a software business, but it really has only one purpose. It issues shares in the company to the public for which it receives old fashioned United States dollars. These dollars are backed by the world’s most powerful military, the largest economy, and is recognized around the globe as “legal tender for all debts public and private”. But instead of putting these dollars to work as investable capital for economic production, what does MicroStrategy do? It simply turns around and uses the real dollars to purchase electronic “crypto currency”.

MicroStrategy now owns $43.4 billion of this digital currency. Logic would tell you that the value of this company should be in the neighborhood of, say, and I’m just guessing here… $43.4 billion? Nope. The company trades with a market cap of $80 billion. “Investing” in MicroStrategy means that you are paying $2 to receive $1. And that $1 may not even actually be $1 because its digital money invented by some random guy with a computer in 2008.

There is a paragraph that I came across recently that seemed to leap from the page. Looking back from their perch in 1940, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd made this observation in Security Analysis: “The advance of security analysis proceeded uninterruptedly until about 1927, covering a long period in which increasing attention was paid on all sides to financial reports and statistical data. But the “new era” commencing in 1927 involved at bottom the abandonment of the analytical approach; and while emphasis was still seemingly placed on facts and figures, these were manipulated by a sort of pseudo-analysis to support the delusions of the period.”

Pseudo-analysis? Here’s another head-scratcher. Let’s see if we can understand the concept called “Yield Farming”. Yield farming is a high-risk investment strategy in which the investor provides liquidity, stakes, lends, or borrows cryptocurrency assets on a DeFi platform to earn a higher return. Investors may receive payment in additional cryptocurrency.

Got it?

Yield farming sounds very sophisticated. It also sounds an awful lot like something Charles Ponzi would have invented were he alive in 2025 instead of 1925. If you prefer time traveling to 1635 Amsterdam, you could easily replace the word “cryptocurrency” with “tulip bulb”. For those of you earning such a high return, I wish you well. When the music stops, someone will be holding an empty bag.

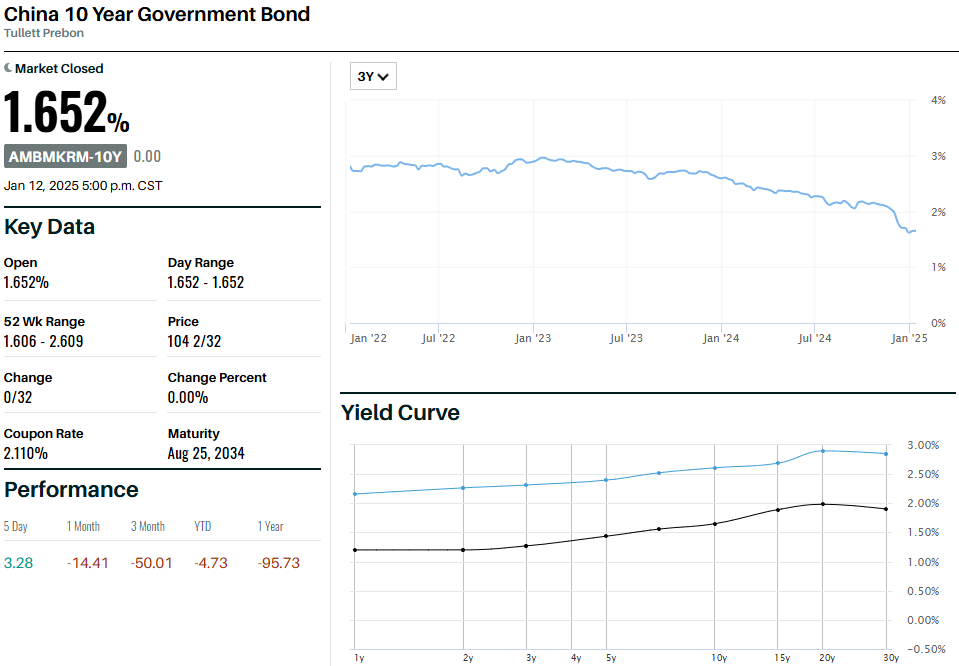

The hunt for rational market prices has led me to Hong Kong. Don’t laugh. The Hang Seng index is down by about 17.5% since its October-2024 peak. Fears of a Chinese debt-deflation spiral have begun to make the headlines as 10-Year Chinese bond yields have tumbled to 1.65%. China has too much real estate, not enough population growth, and massive levels of government debt at the local levels where municipalities became far too dependent upon the real estate market.

Amid the gloom, there are bargains to be found. Earlier, I wrote about the major discount to book value on offer at CK Hutchison (CKHUY). Meanwhile, Budweiser APAC (BDWBY) trades for 14 times earnings and pays a 6% dividend yield. The oil refiner, Sinopec Kantons (SPKOY) can be bought for a PE of 7.6 yielding 6.58%. But Johnson Electric is the biggest bargain of them all.

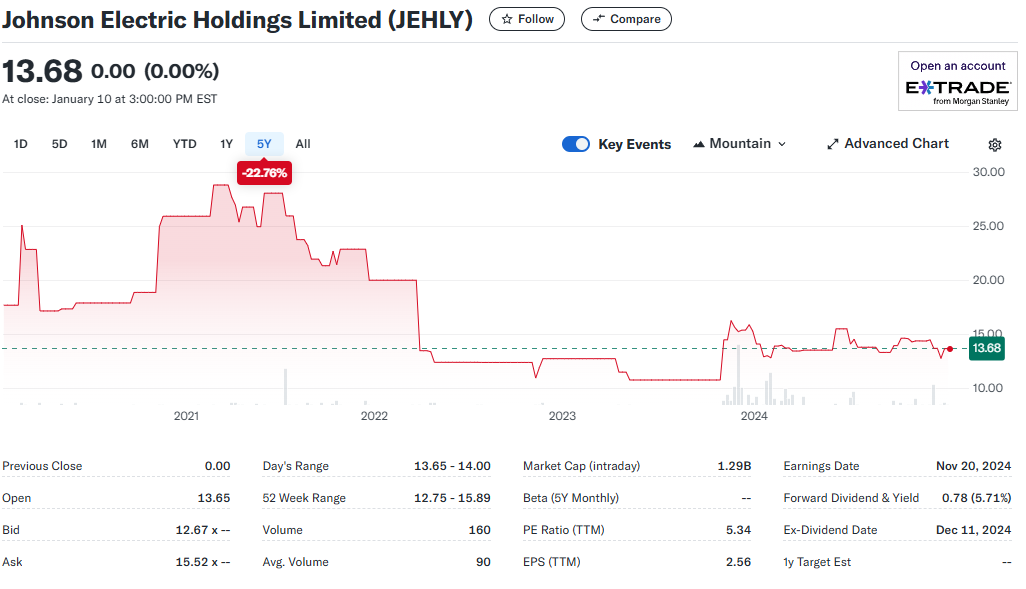

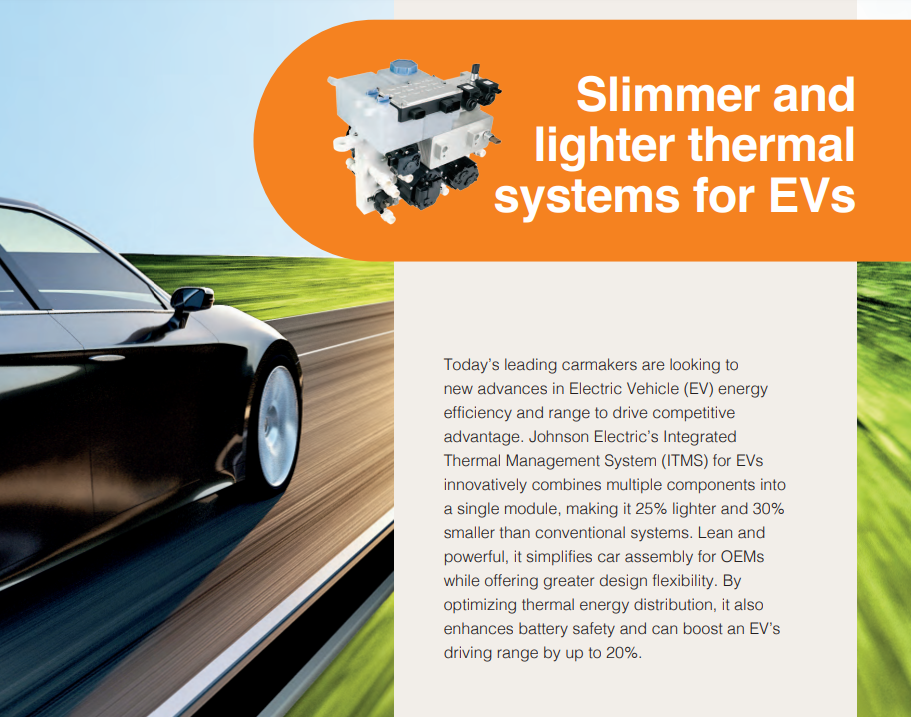

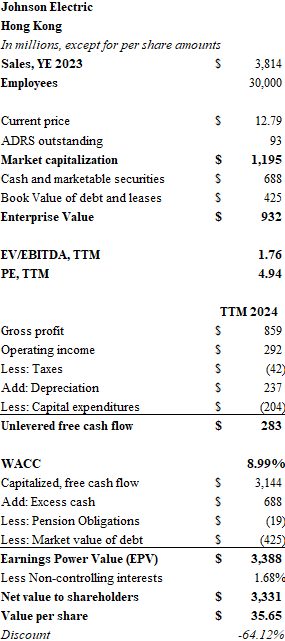

Johnson Electric (JEHLY) shares are valued at $1.2 billion by the market, trading hands at a price-to-earnings ratio below 5x for the trailing twelve-month period ending September 2024. The Hong Kong-based maker of small electrical motors racked up sales of $3.8 billion for the fiscal year which ended in March of 2024. Sales declined over the most recent 6-month period compared with 2023, but gross margins expanded from 22.2% to 23.6% resulting in gross profits over the trailing twelve months at $859 million. Net margins are in the 7.5% range, and operating income for the 12-month period amounted to $292 million.

Johnson Electric makes small motors which are an integral part of the automotive, factory automation, life sciences, and HVAC sectors. The automotive sector accounts for 84% of sales and therein lies the rub. Peter Lynch often warned about buying cyclical companies with low-PEs, and the current cycle may not be favorable for autos. Interest rates in much of the West have placed auto affordability beyond the reach of most consumers, and China faces a possible oversupply problem in its domestic EV market.

Johnson Electric can weather a cyclical downturn. The company was started by Mr. & Mrs. Wang Seng Liang in 1959, so this won’t be their first rodeo. The balance sheet is strong. Nearly $700 million of cash offsets the $425 million of debt. The company is rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s. PricewaterhouseCoopers is the auditor. Johnson Electric has over 1,600 customers with sales split roughly by thirds between Asia, North America, and EMEA. Over 30,000 employees manufacture more than 4 million products per year in factories across the globe.

The stock is exceptionally cheap. Unlevered free cash flow over the most recent 12-month period was approximately $283 million. Using a weighted average cost of capital of 9%, the earnings power value exceeds $3.1 billion. Deduct net debt and some pension obligations, and the intrinsic value of the equity is $3.3 billion or $35.65 per ADR. The current market price represents a 64% discount. The market value is a whopping 50% discount to book value. Meanwhile, the 5.7% dividend yield seems well-covered.

Johnson Electric may be in the early days of a difficult downturn for the global auto sector. The saber-rattling between China and Washington certainly isn’t helpful. Despite these concerns, a 60% discount represents a massive margin of safety. I will be adding Johnson Electric to my portfolio.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

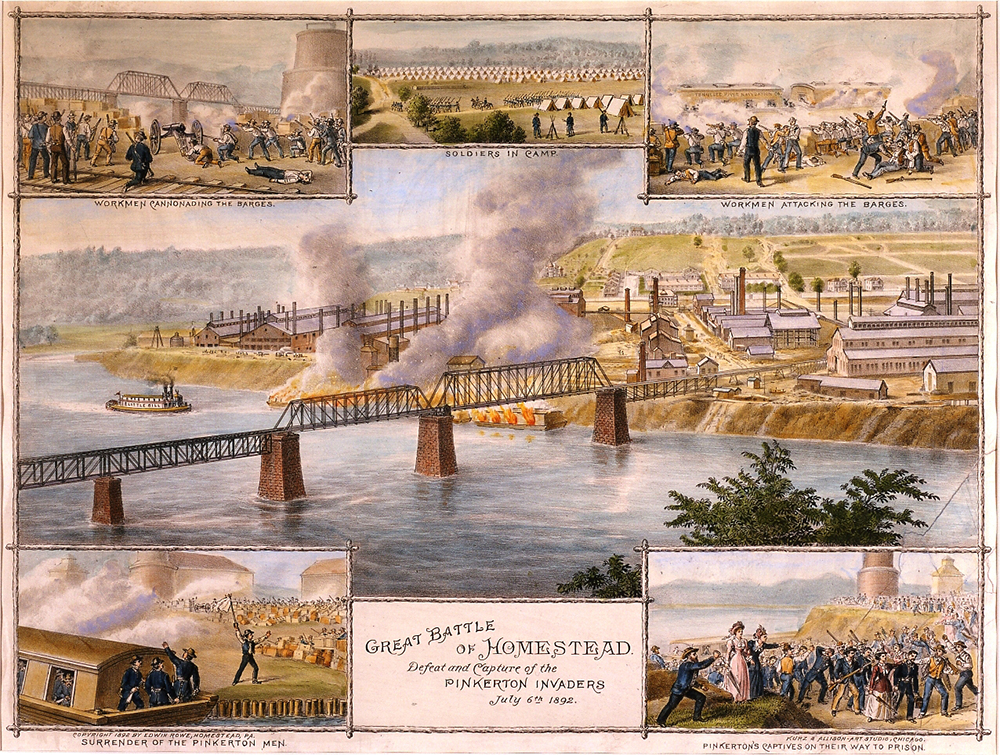

The richest man in the world pondered the unfinished business of his life. Hoping to mend their rift, Andrew Carnegie penned a letter to his former partner. He requested a meeting with Henry Clay Frick, whose towering palace loomed only blocks away from Carnegie’s own Fifth Avenue mansion. The irascible Frick was in no mood to satisfy the old man’s ego. He received the hand-delivered note, wadded the paper and tossed it back to the messenger. “Yes, you can tell Carnegie I’ll meet him. Tell him I’ll see him in Hell, where we are both going.”

Steel is an alloy forged by fire from iron and carbon. Nothing generated more heat and pure carbon than the coking coal of Western Pennsylvania, and nobody made more coke than Henry Clay Frick. Their business alliance provided Carnegie Steel with a ready supply of inexpensive coking coal. Steel from Carnegie’s Pittsburgh empire would form the backbone of America’s industrial revolution.

Carnegie so greatly admired Frick’s relentless pursuit of cost reductions that he proposed that the coke baron should become the boss of his steel business. Carnegie awarded Frick shares in the company. Frick could be tyrannical, but his methods proved successful. Carnegie Steel’s production and profits soared.

But relations between the two industrial titans became testy. Frick’s involvement in the dam failure that caused the catastrophic Johnstown Flood of 1889 killing more than 2,000 set Carnegie on edge. His violent repression of the 1892 Homestead strike tarnished Carnegie’s reputation. They argued endlessly over the price increases for Frick’s coke. Finally, Carnegie invoked the “Iron Clad Agreement”, a long-dormant business clause which provided a mechanism for a partner’s removal from the business. By January of 1900, Frick was out.

Iron has always been synonymous with strength. Herman Knaust chose the name Iron Mountain for his record-storage business in upstate New York during the 1950’s. As corporations produced millions of paper documents, their safe preservation became paramount. Knaust saw the need to store them in a secure facility where they could not be damaged by fire, theft, or even atomic blasts.

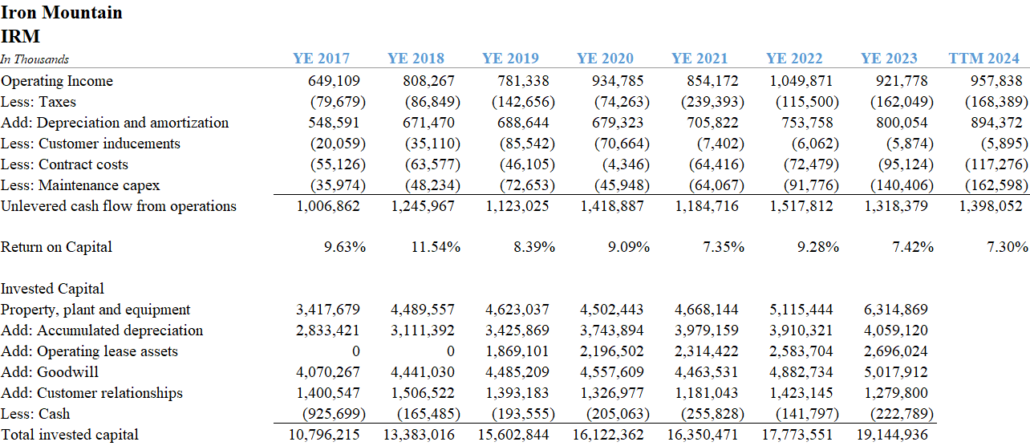

Iron Mountain (IRM) has grown to become one of the world’s leading document and data storage companies with over $6 billion in revenues over the trailing twelve month reporting period ending September 2024 (TTM3Q). Storage generates 62% of revenues, and the remainder comes from services, including document processing as well as the de-commissioning and disposal of used IT equipment. Despite the high concentration of service revenue, Iron Mountain trades as a real estate investment trust. The company has over 7,400 facilities in 60 countries, with 98 million square feet of floor space and 731.5 cubic feet of storage volume.

The main attraction for Iron Mountain during the past four years, and its most likely source of growth for many years ahead, is the construction and operation of data storage facilities. These are the buildings that house IT servers and cloud storage infrastructure. The demands for robust computing power for artificial intelligence has set off a race to develop data centers. Iron Mountain aims to be at the leading edge of the AI infrastructure boom.

The current data center portfolio has 26 locations with 918 megawatts of storage capacity. 327 megawatts is leased or under contract, 184 megawatts is pre-leased, leaving 357 megawatts yet to be leased. The company expects 130 megawatts to be leased for the year 2024. At the end of 2023, Iron Mountain had $1.6 billion of development in progress.

Data center construction requires immense amounts of capital. Cushman and Wakefield, a leading real estate advisory and brokerage firm, recently released a 2025 Data Center Development Cost Guide. The average cost to develop one megawatt of “critical load” (building and IT equipment) averaged $11.7 million in the US. In other words, the cost to double Iron Mountain’s data center capacity would be $10.7 billion.

It will be difficult for Iron Mountain to grow its data center portfolio without issuing more stock. The company’s status as a REIT requires it to distribute most of its income, so retained earnings are minimal. Operating cash flow over the TTM3Q summed to $836 million, and $769 million was paid to shareholders.

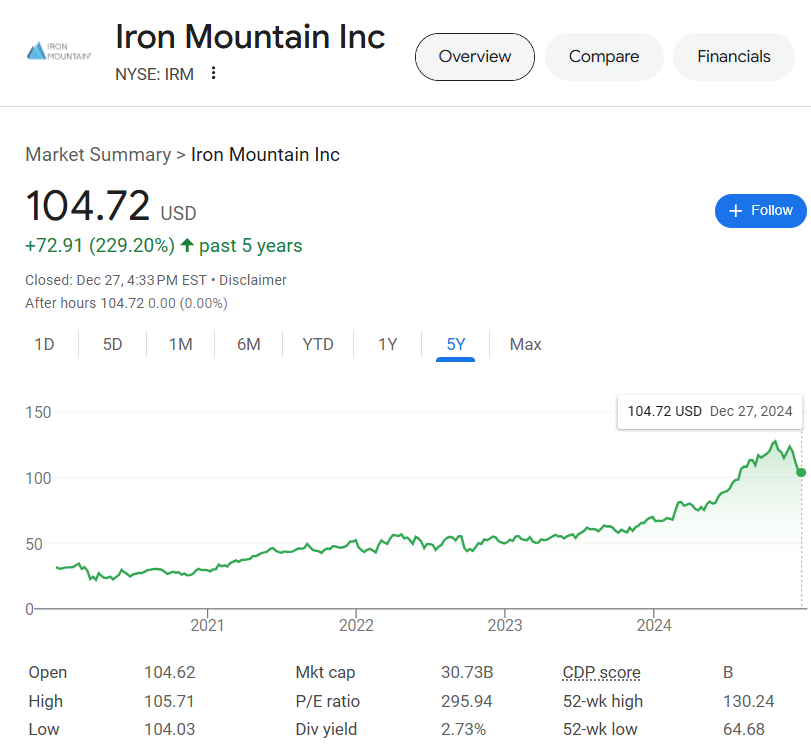

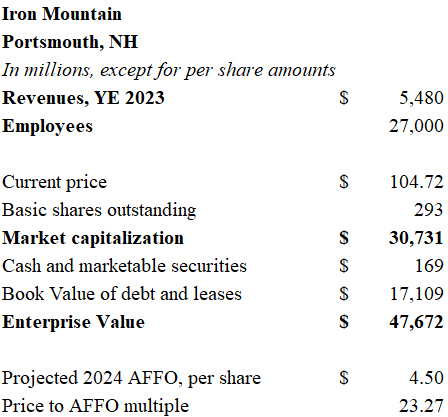

Iron Mountain equity trades at a market capitalization of $31 billion and debt and leases account for $17.1 billion, giving the enterprise a value of $48 billion. The company is rated below investment grade by Standard and Poor’s at the BB- level. The current weighted average cost of the company’s debt is 5.67%, but additional debt in today’s current rate environment would cost IRM 6.7%. Additional leverage is not a prudent source of capital unless it is paired with the issuance of new stock.

At today’s market price of $105.73 per share, Iron Mountain trades at a 45% premium to its intrinsic value.

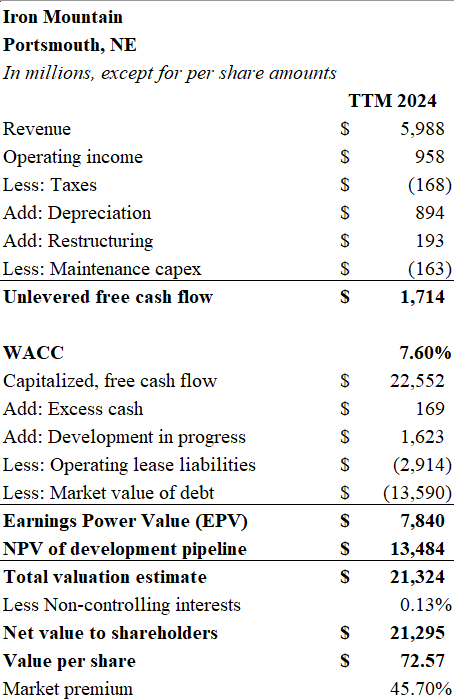

I’ve taken a two-step approach to arrive at a value of Iron Mountain’s equity closer to $73 per share. Using the earnings power valuation (EPV) method, I took the free cash flow for the business and discounted it at the weighted average cost of capital of 7.6%. The aforementioned 6.7% cost of debt (5.53% after taxes) account for 34.8% of capital, and 8.7% was used as the cost of equity. I simply priced equity 2% over the market cost of debt. Unlevered free cash flow of $1.7 billion capitalized at 7.6% is $22.5 billion. Subtract the market value of debt and leases ($13.59 billion and $2.91 billion, respectively), and the net EPV is $7.84 biilion.

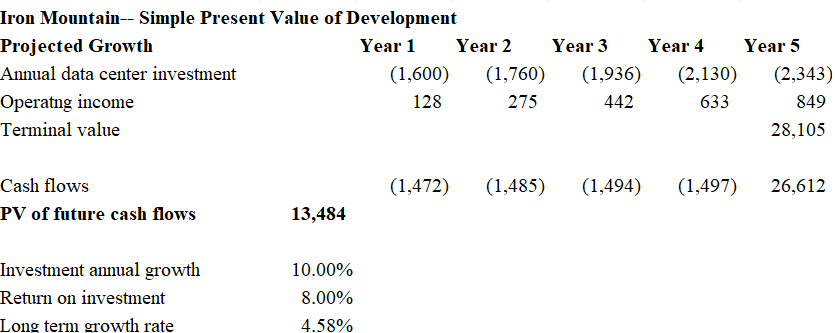

Next, I went fishing for the simplest possible explanation for the gap between the market value of the business and the intrinsic value of its current assets – the unknown future development pipeline. I created the most basic discounted cash flow projection possible. I assumed that IRM placed a development pipeline into service that started with $1.6 billion in Year 1 and grows by 10% annually over five years. I assumed the data centers earn an 8% yield on cost. The terminal value of the business reflects perpetual growth at the current Treasury 10-year yield. The present value of future cash flows, discounted at 7.6% amounts to $13.5 billion. The net value of these two figures, after adjusting for noncontrolling interests is $21.3 billion, or $72.57 per share.

Readers may say that my discount rate is too high. After all, institutional quality real estate continues to trade at capitalization rates between 5% and 6%. I would argue against a lower discount rate for two reasons: One, the faster that the world embraces digital data, the more IRM’s legacy businesses of document processing, storage and destruction diminishes in value. Two, the discounted cash flow model, while laughably over-simplistic, is also generous. Few institutional real estate developers earn much more than a 6% yield on their costs in the current environment. More importantly, my model makes no allowance for the rapid depreciation of the equipment and possible obsolescence of the facilities as more sophisticated ones are built.

Frankly, my earnings power valuation is also quite generous. I add back restructuring charges, despite their seemingly recurrent nature. The company has incurred nearly $670 million in restructuring charges since 2019. I make a deduction for the ongoing capital needs for the facilities, but no deduction is made to unlevered free cash flow for the “customer inducements” and “contract costs” that exceed $100 million annually. These charges appear among capital items rather than on the income statement where they probably belong.

More conventional metrics also point to Iron Mountain’s inflated valuation. The company offers a 2.7% dividend yield – thin gruel in a market where 10-year TIPS can be bought with a 2.23% handle. Meanwhile, IRM trades at 23.5 times adjusted funds from operations (AFFO) projected to be $4.50 per share for 2024.

Iron Mountain will be forced to raise equity in large amounts to fund the data center program. The additional shares will be highly dilutive if the investments can’t yield more than the cost of capital.

Iron, carbon, steel, silicon…the future beckons.

Until next time.

Note: Meet You in Hell is an entertaining book by Les Standiford, published in 2005, that chronicles the formation and dissolution of the relationship between Carnegie and Frick. Chapter One colorfully describes the “letter incident”.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.