Rocco Schiavone is a chain-smoking police investigator who has been banished to the Valle D’aosta in the Italian Alps in the humorous and dark cop drama that bears his name. Early in the series, Rocco introduces us to his version of Dante’s hell. Murder is a “level 10 pain-in-the-ass”. Dealing with magistrates is at level 8. A closed tobacco shop is level 9. If Rocco owned apartment buildings, he’d probably list capital improvements on old buildings as a level 7.

We own and operate a collection of older buildings that were constructed in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Let me tell you something. They eat money. Sh*t breaks all the time. Literally. Air conditioners, pavement, carpets, decks, windows, appliances. Depreciation is real, my friends. Yes, it’s a lovely tax-deductible non-cash expense in the early days when a property is new. But as the depreciation wanes, you find yourself replacing capital items at a cost well in excess of the tax benefits.

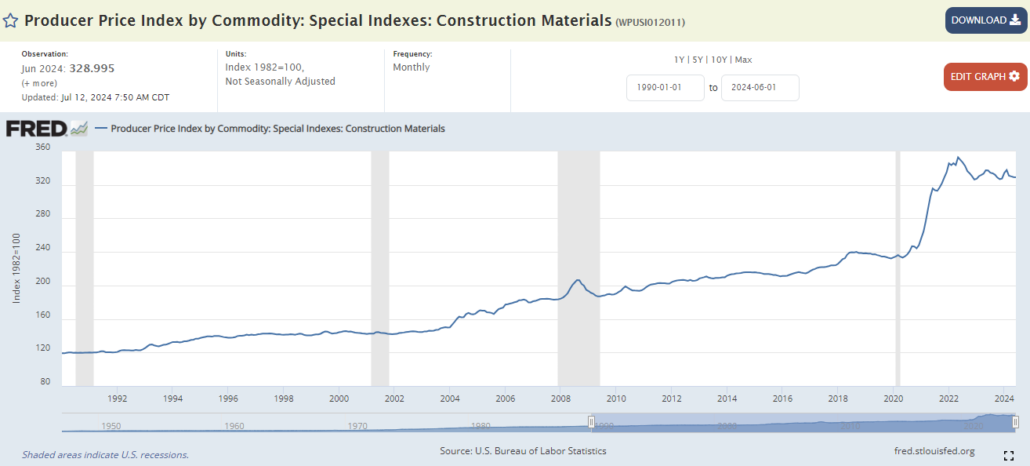

This is the problem of old dollars. It’s even worse in an inflationary environment. If you have a parking lot that was built in 1990 for $20,000, you’ve got zero depreciation benefits today. It’s over. Now you need to replace the pavement. Guess what? It costs $35,000. The greatest inflation in 40 years in the pandemic boom made this problem so much worse. About $10,000 of that parking lot cost increase occurred in the span of four years. Four years! Maybe Rocco would elevate this to a 9.

Buffett lamented the pain of inflation when discussing Berkshire Hathaway’s BNSF railroad. He figured it would cost $500 billion to replicate the railroad today. Depreciation and amortization amounted to $2.5 billion in 2023. In 2024, the railroad announced a $3.9 billion improvement plan. Old dollars vs new dollars. Inflation destroys old dollars. Level 9 agony.

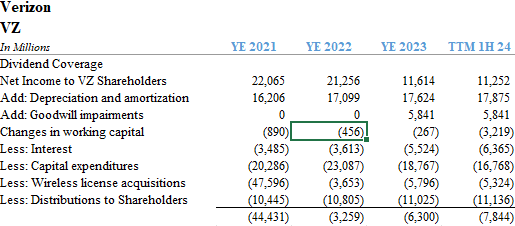

Therefore, a capital-intensive business that is not expending asset replacement dollars at levels significantly ABOVE current depreciation is probably under-investing in the year of our Lord, twenty twenty-four. Take Verizon (VZ). There are only three major wireless carriers in the US. The word “oligopoly” comes to mind. The dividend yield is so tempting at 6.6%. You might think that it’s the sort of holding widows and orphans should cling to for the quarterly stipend. Yet, you would be sorely mistaken.

Verizon doesn’t earn enough to cover it’s dividend when you take into account the immense investment needed to maintain a robust wireless network. Verizon is making capital expenditures that are roughly equivalent to depreciation charges. Four years ago, you might think this was a satisfactory situation. Today? They are behind the curve.

Verizon revenues have been flat for three years at $133 billion. Depreciation on a $307 billion asset base runs to roughly $17 billion per year. The market capitalization for VZ is $168.8 billion and the company has net debt of $148 billion. I think debt-holders will do just fine, but the equity holders will continue a slow grind into obscurity. The company can’t afford it’s hefty dividend of $11 billion per year, and if you account for investments in wireless licenses, the business is cashflow negative.

Defenders may argue that Verizon has been on a costly multi-year 5G network investment path that is about to wind down. I suspect not. If there’s one thing we know about bigger, stronger, faster technology demands, there will be a 6th, 7th and 8th generation waiting in the wings. I’m not even considering the ball-and-chains legacy land line business, pension fund requirements, and the whiff of litigation from aging lead-encased wires from the NYNEX days.

Capital expenditures amounted to $18.8 billion in 2023, so they are running about 7% higher than depreciation. What about inflation? If construction costs are 40% higher in four years and BNSF is spending 40% more, shouldn’t Verizon? The stock’s 30% decline since 2021 reflects a dwindling return on capital. Returns have declined from a healthy 12% in 2021 to just about 7.8% today. Let’s file Verizon in the value trap category. Avoid the siren song of that big dividend.

I’m getting a little weary of Charlie Munger quotes, to be honest. Don’t get me wrong, there’s no question that we recently lost an intellectual giant and a man of high moral character. His investment acumen and the genius ability to cut straight to the heart of a matter was legendary. But I think the elevation of his aphorisms to a form of business gospel reduces our own capacity to think for ourselves. He was just a man. Mortal. It’s ok to have heroes, but it’s not safe to put them on pedestals.

I imagine Munger could be insufferable at times. A real crusty bastard. Did you ever see his dorm design for USC? He must have been a dynamo when he was earning his capital as a lawyer and real estate developer. You probably regretted getting in his way. He was unapologetic about his desire to be rich and I’m sure he never suffered fools gladly. Ah, but yes, at his core he was among the wisest of the wise. So, after a long-winded preface, here is my Charles Munger quote: “If something is too hard to do, we look for something that isn’t too hard to do.”

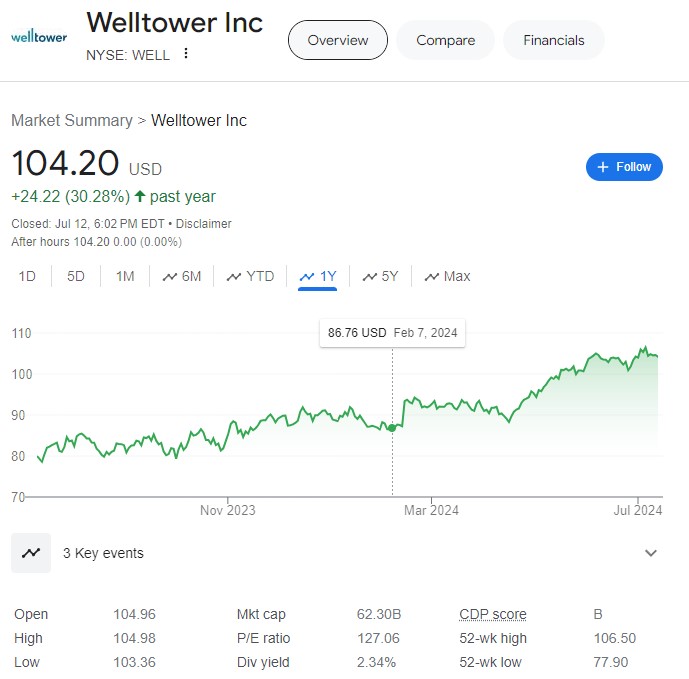

I’m filing Welltower in the “too hard” category. Welltower (WELL) is a $62 billion market cap REIT that owns senior living facilities and medical office buildings. WELL is also a bank of sorts. It lends money to developers of properties. It has JVs with a bunch of developers. Some of the assets are leased triple-net to operators, many are operated directly by Welltower. The company is also a prolific issuer of new stock and an expert at churning real estate. It’s head-spinning and hard to completely grasp. This is a company whose CEO, Shankh Mitra, quoted Jensen Huang in the annual report. I’m not saying that running real estate for old people doesn’t have much in common with NVDIA. Ah hell, who am I kidding? This is the vibes economy. Everything runs on NVDIA.

In fairness to Mr. Mitra, he also candidly told a 2023 audience, speaking of the industry, “On average, in the last 10 years we haven’t made any money for capital [providers].” The oversupply conditions of the middle part of the last decade were just beginning to recede when COVID hit. Now, prospects for better economics seem to finally be destined for senior housing operators due to the unfeasibility of new supply and the rapid aging of the boomer generation. The stock market seems to agree. The stock has run up 24% since the start of the year as occupancy and margins vaulted upwards.

Despite Mr. Mitra’s humility, there’s not much for me to like about the company as an investment. A REIT with a mixed collection of properties doesn’t deserve to trade at a higher multiple than apartment buildings, and certainly not better than medical office buildings. The demographic story has legs, I’ll grant you that. But you can say that about Skechers slip-ons or Hey Dudes.

I was first intrigued by Welltower late in 2022, when Hindenburg published a report questioning the absorption of some troubled JV assets. The short-seller specifically cast doubt upon the relationship with Integra Healthcare Properties. There was a lot of mystery about Integra. Hindenburg called it a phony transaction. Integra’s website is still just a collection of canned photos of smiling elderly folks with zero substance (at least they updated the copyright date to 2024!). Crickets from the market.

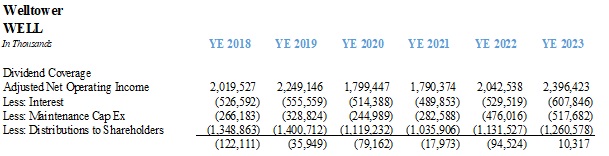

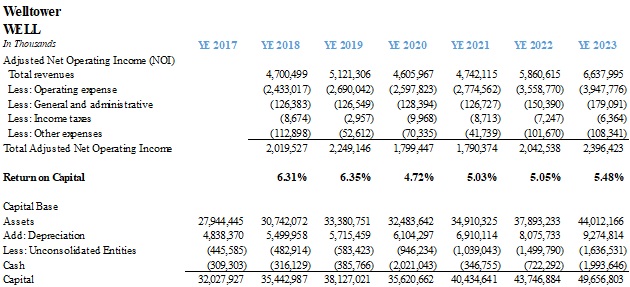

In my view, the only thing Welltower is guilty of is being exceptionally underwhelming. Welltower generated $6.4 billion in revenues during 2023. Property operating expenses absorbed 59% of revenues vs 52% of revenues in 2018. The industry sees itself getting back to pre-pandemic margins as staffing issues abate. I’m not so sure. States have ramped up calls for minimum staffing levels. The industry is also facing a lot of scrutiny about Medicare reimbursements. I don’t know enough about these challenges, so I can’t opine about the true risks to the company. I just know they exist.

What I can tell you is that I don’t think Welltower has much room to expand its distributions to shareholders above it’s current paltry yield of 2.35%. Once you deduct maintenance capital items from operating income and interest on over $15 billion of debt, there’s not much left.

No matter how many assets the company churns, the return on capital seems mired in the mid-single digits. The company has issued over $14.4 billion of stock since 2018, acquired $18 billion of assets during the period, while selling $9.9 billion. All this huffing and puffing hasn’t produced a formula that shows it can distribute increasing levels of cash to shareholders in a sustainable way. It is not unfair to say that some of the distributions are being funded with new equity. That’s not a great recipe. And for a CEO that says there aren’t many opportunities for new construction, the deal guys didn’t get the memo because Welltower had about $1 billion of construction in progress at the end of 2023.

Apparently, the market completely disagrees with me about the Welltower story. A 25% stock increase for a senior housing play is impressive. I am equally impressed that Welltower just raised over $1 billion of new debt at 3.25%. Is it pure debt? No, not for Welltower. It’s another dilutive offering. A convertible note due in 2029 that vests once the stock price rises 22.5%. I’m not sure who buys such debt when the five-year Treasury yield can be had for 4%, but it was probably a couple of fund managers who were feeling as frisky as Wilfred Brimley and Don Ameche in swim shorts.

So, I bid you adieu, Welltower. Low returns on capital, poor coverage on a low dividend yield, a churn of assets, acting like a loan shark, pumping new stock and forming a lot of unconsolidated JV’s… sounds like this one’s just too hard.

The easy column. I missed a fat pitch. I looked at it and didn’t have time to get my bat off my shoulder. It may not be too late, but I still need to dig deeper. Hat tip to Adam Block on social media who noticed Peakstone Realty Trust (PKST) was trading around $11 per share on July 10, giving the REIT a market cap of about $382 million. It sported a dividend yield north of 8%. Alas, it ran up 20% in two days. It still trades well below the $39 per share of last summer, so there may be juice left in the squeeze.

Peakstone had $436 million in cash at the end of March with a book value of real estate (excluding depreciation) in the neighborhood of $3.3 billion. Yes, there is debt of $1.4 billion. It costs Peakstone about 6.75% to finance the loans which roll over during the 2025-26 period. So, there’s loan renewal risk as well. But this is a pretty good portfolio of assets. The buildings consist of office and industrial space, but they’re mostly leased to single users with high credit such as Pepsi Bottling, Amazon and Maxar. Total square footage of the assets is 16.6 million. Net operating income for the quarter was $47.6 million. As far as I can tell, the market was essentially ascribing zero value to the assets at the beginning of last week. Even if you figure a monstrous 12% capitalization rate on an annualized run of quarterly NOI, there is adequate cushion above the debt. Seems like one to dig into. Easy? No. Simple to comprehend? Yes.

The Code of Hammurabi dates back to 1750 BC. These ancient laws contained the essence of the first banking contracts for managing loans. The farmer would borrow a bushel of seeds, reap the harvest, give the king about seven bushels of rye and keep three bushels for the family. In the modern parlance of Hammurabi’s descendant Jamiz ur-Dimon, a sound business endeavor earns positive leverage: the return on one’s capital investment should exceed the cost of borrowed money – the rate of interest. What happened if the loan required the farmer to pay back eleven bushels? It would probably end with the removal of a finger or three.

As crazy as things got during the pandemic boom, the basic premise of positive leverage remained intact. Purchases of apartment complexes yielding 4.5% bordered on insanity, but at least lending rates could be found in the 3% range. Now, we have entered a strange, new post-pandemic era. Buyers of apartments have reduced their purchase prices in order to earn a higher rate of return on their capital. Low 5% levels are the reported “capitalization rates” that many buyers are willing to pay. This sounds logical until one realizes that the cost of fixed rate debt today is about 6%. Watch your fingers.

Why would a buyer accept such a meager deal? Three reasons. One, they are willing to earn a return on their own equity that is below the cost of debt. This seems nonsensical. Very liquid low-risk alternatives abound in the form of humble T-bills or, say, Chevron stock with a 4.2% dividend yield. Two, some believe interest rates will decline in the future. There are signs that such joy awaits: The Fed seems poised to reduce rates as inflation slowly approaches the target 2% level.

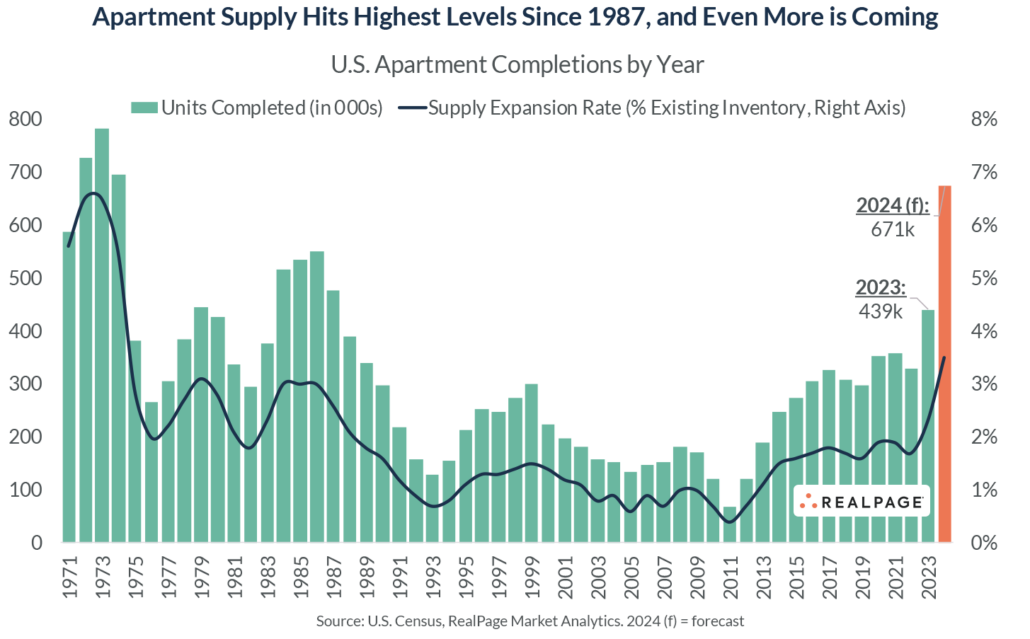

The third reason takes the opposite tack. There is a belief that inflation will lift rents faster than expenses in future years, and negative leverage will pleasantly reverse itself. This theory has merit. The greatest supply of apartments since the 1970’s is about to come to an end. Construction costs and interest rates have risen so high, that most new developments are unfeasible. Home purchases are out of reach for most Americans. The incumbents have a long runway to raise rents once the period of apartment oversupply abates. This is the theory behind KKR’s purchase of Lennar’s multifamily portfolio.

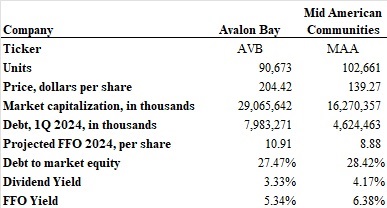

Publicly traded apartment real estate investment trusts (REITs) benefit from a low cost of debt and continue to earn positive leverage. Unlike their private competitors who must grovel for 6% permanent loan rates and 7% construction loan costs, the REITs have healthy balance sheets and can borrow at 5%. Mid-American Apartment Communities (MAA) and AvalonBay (AVB) are two of the largest landlords, and they are projecting returns of 6.5% on their (much reduced) development pipeline.

Both firms locked in low-rate long-term financing during the pandemic. Even as notes mature, healthy balance sheets at MAA and AVB provide pricing power in the bond market. In early January, MAA raised $350 million of debt at 5.1% for ten years – just slightly above a 100 basis point spread to the Treasury note. Assuming their development yields hold to projections and leverage is in the 30% range, they should be able to drive returns on equity to low 7% levels. Not fantastic, but sufficient to sustain dividend yields in the 3%-4% range and grow values in line with the broader economy. Both companies reported record low levels of resident turnover as home purchases have become less affordable.

Not everything is rosy for the REITs. The apartment supply hangover has arrived to pandemic boomtowns like Dallas, Atlanta, Houston and Nashville. Indeed, both MAA and AVB offered some sobering news: rents on newly vacant units were trending negatively in the first quarter. MAA, focused primarily on sunbelt markets, posted a negative 6.5% new lease rate. AVB was closer to negative 0.5%. Fortunately, high resident retention and rent increases of 5% on renewal leases kept the top line growing at both companies. Neither of these stocks is cheap. Taking projected 2024 funds from operations (FFO) – the preferred measure of operating earnings for a publicly-traded REIT – AVB trades at an FFO yield of 5.35% and MAA trades at a 6.43% forward FFO yield.

Meanwhile Farmland Partners (FPI) presents the perils of negative leverage. FPI owns and manages farms (177,000 acres) and has a market capitalization of $553 million. FPI shares peaked at $15 in 2022 and sit at $11.50 today. The dividend yield is a paltry 2.09%. Corn prices have round-tripped during the past five years from $4 per bushel in 2019 to $8 per bushel in 2021, and back to around $4.25 today. Not even Russia’s invasion of one of the world’s top grain-producing nations was enough to sustain wheat prices much higher than $6 per bushel.

Given these daunting agricultural prices, FPI doesn’t offer shareholders much value. The company generated $57.5 million in revenues in 2023 and had $31.3 million of EBITDA. The company spent about $25.6 million on interest and divdends to preferred shareholders, leaving just $5.7 million for common shareholders. This diminutive profit is not sufficient to cover the common shareholder dividends of $12.2 million.

FPI has been selling land to cover its dividend, and really, this is probably the best path forward – sell assets, reduce debt and retrench for the future. The floor on the stock is probably the market value of the land. A swag number of $6,000 per acre means there may be well over $1 billion of land vs $480 million of debt and preferred stock.

Positive leverage feeds your family. Negative leverage only feeds the king.