Shiseido is a Japanese cosmetics company founded in 1872 by Arinobu Fukuhara, the former head pharmacist for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Fukuhara opened a pharmacy after leaving the navy and added a soda fountain after visiting stores in the United States. In 1917, the company introduced face powder and began expanding its footprint. Today, Shiseido is one of the world’s leading cosmetics businesses with 2024 sales of nearly $7 billion.

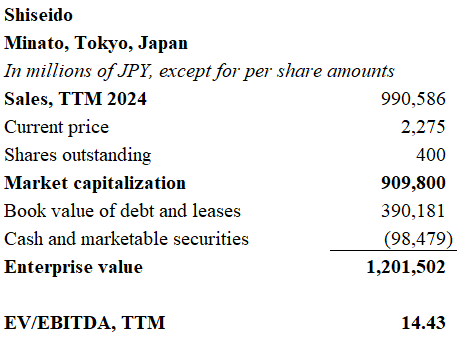

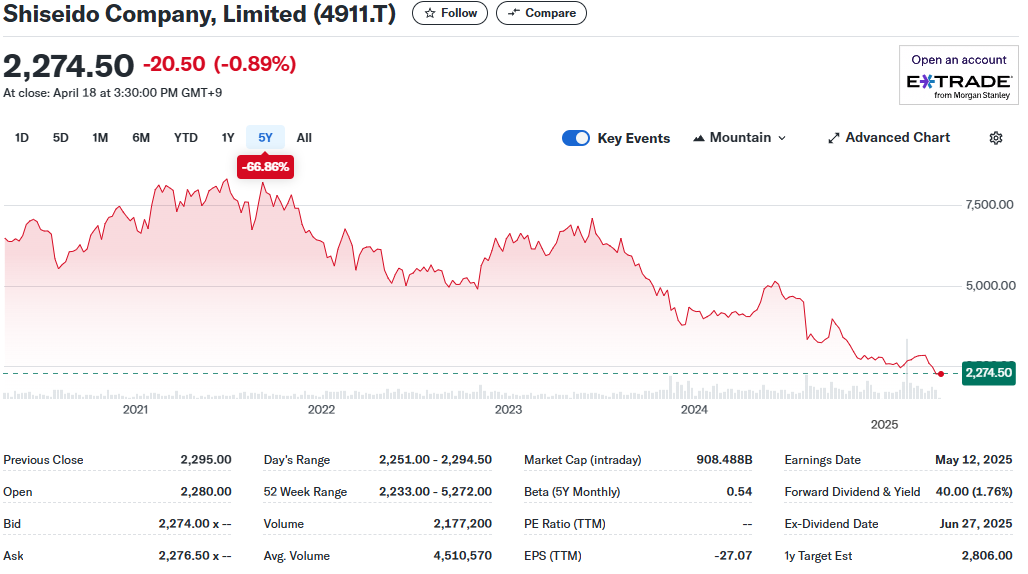

In addition to Shiseido products, the company owns leading brands such as NARS and Cle de Peau. Drunk Elephant is among its up-and-coming marks. Unfortunately, revenues have been on a downward trend since 2022 when sales to China began to decline. The recession caused by the Chinese real estate collapse has been a problem for most luxury brands. Shiseido (SSDOY) stock has fallen by over 66% over the past five years, and the market capitalization stands at $6.4 billion (909 billion JPY).

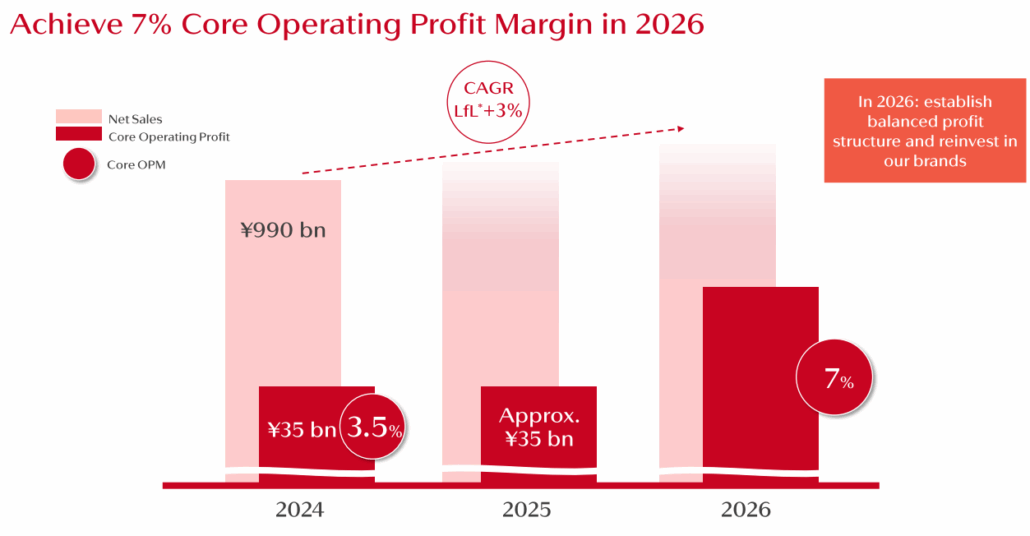

I became interested in Shiseido when I saw that Independent Franchise Partners, the London-based activist firm, had taken a 5.2% position in the company. Japan’s notoriously sclerotic corporate culture is slowly becoming more accountable to shareholders. The company has introduced its 2026 “Action Plan” which aims to grow sales and expand margins. Changes can’t come fast enough. Shiseido stumbled to a loss of 9.3 billion yen in 2024.

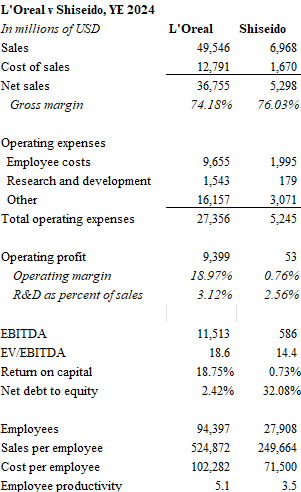

The contrast with the French cosmetics giant L’Oreal is stunning. L’Oreal posted sales of $49.6 billion last year, and operating profits of $9.4 billion. L’Oreal (LRLCY) has a market capitalization of $208.7 billion and trades at an EV/EBITDA multiple of 18.6x. L’Oreal boasts a return on capital nearing 19%. Operating margins are a healthy 19%. Meanwhile, Shiseido trades for a multiple of 14.4x with much more debt than the French company.

The most glaring difference between the two glamour brands is the level of employment costs. L’Oreal generated nearly $525,000 per employee last year while Shiseido sales-per-employee amounted to roughly $250,000. Although Shiseido employees are about $30,000 less expensive per head, the overall labor effectiveness for the French company is more than 35% better.

I don’t have any insights into why such a disparity exists. Japan has a famously attentive customer service culture that may demand a higher number of sales staff. Perhaps L’Oreal outsources more aspects of their business. Whatever the case, Shiseido will have to dramatically reduce headcount if they are going to reach their stated goal of 7% operating margins.

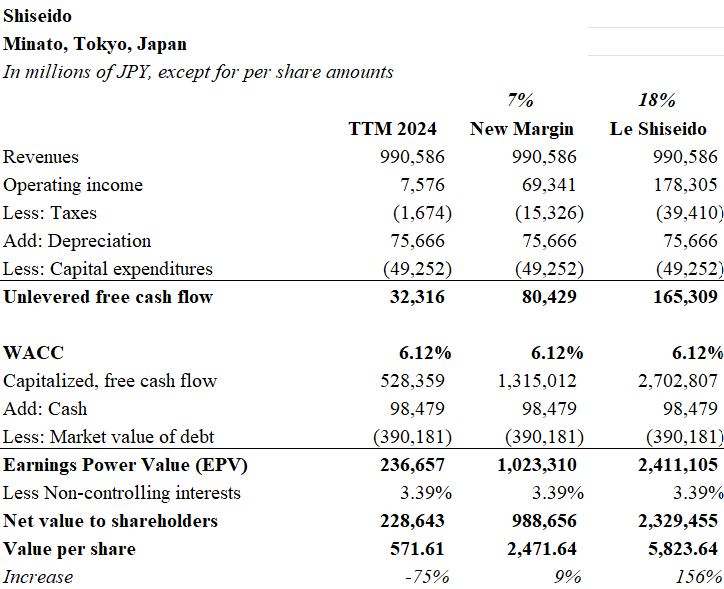

Judging by 2024 financial results, Shiseido remains overvalued despite its protracted market slump. I used an earnings power valuation method to calculate the value of the business based upon last year’s numbers. I applied a discount rate of 6.12% for capitalization purposes. Debt, 30% of the weighting, costs Shiseido 1.64%. I estimated the cost of equity to be 8.2%, given Japan’s higher default spread and equity risk premium. On this basis, Shiseido has a value of less than 228 billion yen. The result of my equation is more punitive than illustrative – Shiseido book value exceeds 632.4 billion yen.

What happens if the company achieves the sought-after 7% margins? I adjusted the numbers and the market capitalization reaches 988 billion yen, only slightly better than the current market price. Finally, I wondered what could happen with L’Oreal’s margins. “Le Shiseido” is worth about 2.3 trillion yen – or about 150% more than its current value.

I’m pressing the pause button. There is no margin of safety at the current price, and the resuscitation of the Chinese consumer will probably take a few more years. The leadership of Shiseido recognizes the problem, but it’s not clear that the “Action Plan” goes far enough. I’m sure Independent Franchise Partners won’t find the projections sufficient for their return requirements.

Will radical changes come to Shiseido? Japan, Inc. seems serious about unlocking shareholder value. Even beleaguered Estee Lauder (EL) manages an operating margin of 8% excluding impairment and restructuring charges, so the target seems underwhelming. Shiseido has rarely delivered returns on capital in excess of the high single digits – even in the heady days of lockdown makeovers.

An opportunity may arise to own part of a 150-year-old brand which is a staple of the Asian beauty market for what it traded for ten years ago, but it will require much more than an “Action Plan”. Some day, perhaps soon, a slimmed-down Shiseido may eventually beckon from the mirror.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Physics was never boring. At least not when Richard Feynman was teaching. Despite the complexity of his subjects, he kept things simple and fun. Feynman was awarded the 1965 Nobel prize for his work on quantum electrodynamics. His method for learning a topic was to be able to write about it in such a way that a 12 year-old could understand. “Anyone can make a subject complicated but only someone who understands can make it simple,” explained Feynman. That’s why I write down my thoughts, theories and formulas for various investments. To learn. To teach myself.

I fall short of Feynman’s dictum of elegant simplicity on most occasions. Never more so than my recent attempt to explain the valuation of Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP) using the firm’s consolidated financial statements. It’s not entirely my fault. Understanding BIP’s organizational chart practically requires a degree in quantum electrodynamics.

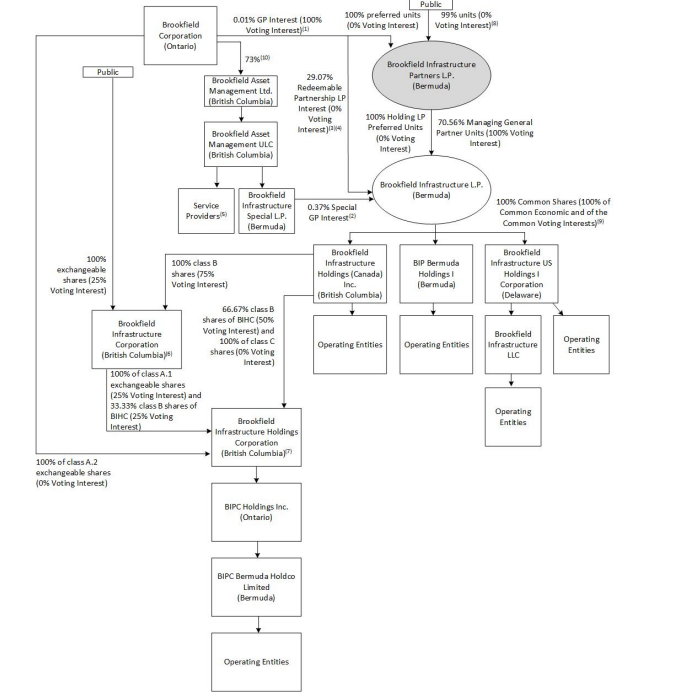

I think BIP management prefers things to be as complicated as possible. BIP is a publicly traded limited partnership. They obfuscate the value of their underlying utility, transport and midstream properties through a web of holding companies and partnerships, most of which are offshore. Buffett would surely file BIP in the “too hard” pile.

BIP is far from a monolithic operating company with a series of divisions. BIP is really a loose confederation of businesses – virtually all of them joint ventures with third parties – that pass cash to limited partners only after everyone else takes their cut. BIP limited partner units trade for nearly three times book value despite only having a claim on about 16% of the equity in the collective companies.

The price is held aloft by a generous 6.23% dividend yield. I concluded that BIP limited partner “equity” is probably just mezzanine debt in masquerade. The company’s allocation of “maintenance capital expenditures” in non-GAAP “adjusted funds from operations” gives investors a flawed belief that dividends are easily supported by operating cash flows.

In short, I am coming around to the thinking of Keith Dalrymple who has produced comprehensive research on the company. He argues that such a holding company structure deserves to trade for book value, and no more. Just like the old Canadian holding company Edper, the Brookfield game is to layer debt at the asset and corporate level and shuffle cash around as needed. Dalrymple’s most recent post explains that BIP is papering over the erosion in net asset value by writing-up the value of illiquid holdings in the accumulated other comprehensive income account.

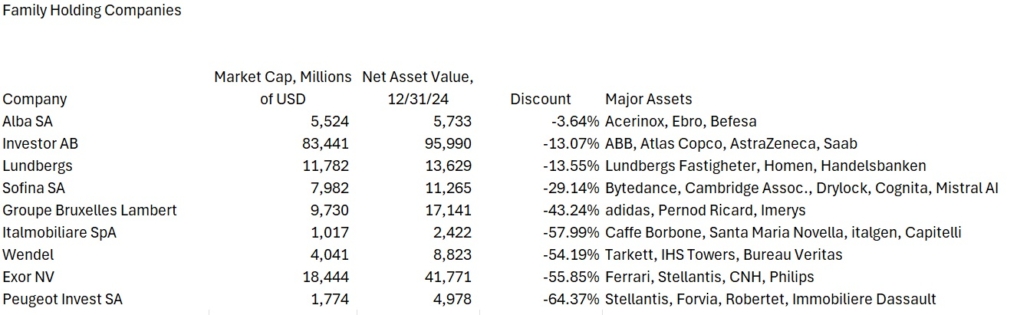

What about other investment companies? Are they trading above book value? I ran the numbers on some large European holding companies. Unlike BIP, the market capitalization for each company is less than the net value of its assets. In most cases, the discount is greater than 30%.

These are mostly multi-generational wealth vehicles for legacy industrialists which also offer shares to the public. The most well-known company is Exor, the holding company for the Agnelli family of Italy, the pioneering family behind the Fiat empire. Exor holds portions of several public and private companies, most notably Stellantis, Ferrari, CNH Industrial and Philips. No, legacy automakers do not inspire much hope these days. However, I would argue that the assets held by the heirs of the Wallenbergs and their ilk are far superior to the Frankenstein that BIP has stitched together among toll roads in Brazil, Alberta LNG factories, and Indian cell towers.

If the holding companies for some of the world’s leading industrial families trade below net asset value, why should BIP sell for a premium?

Tariff Don’t Like It

I am also not Feynman-qualified to lecture on the topic of tariffs. However, I do believe that in the long run, most countries specialize and benefit from what is known as comparative advantage. You want your Swiss making watches, your Italians making pasta, and your Mexicans making tequila. I wouldn’t drink Swiss tequila. If China is producing steel below cost and dumping it in the US, yes, tariffs should apply. But there’s a reason why Bangladesh and Vietnam produce most of our clothes now. We produced most of the textiles of the world in the 1880s to 1900s. I’d prefer to live in the 21st century, thank you very much.

I am traveling in the low country this week. A visit to Savannah got me wondering about cotton. I imagined that the end of slavery meant that the price of cotton rose dramatically after emancipation. Did higher labor costs translate into higher cotton prices after the Civil War? Could that period of history be an analog for 2025?

The opposite happened. Cotton prices dropped. By a lot. Historian James Volo has a well-written summary. There were a couple of reasons for the decline. One, English textile manufacturers responded to the wartime shortages of the American South by sourcing more cotton from Egypt, Brazil and Africa. Two, the cotton gin made production so efficient that the supply of cotton boomed. In fact, American cotton production kept rising until 1937.

What’s the lesson here? Sudden price adjustments might produce unexpected consequences. Bulgarian pasta could just turn out to be a pretty decent substitute for that pricey penne from Pisa. Robot weaving machines in Cleveland might replace millions of Bangladeshi weavers. But that manufacturing renaissance on the banks of Lake Erie? It may not be coming after all. Three programmers in an office building on the outskirts of Hyderabad may control those looms.

Prices send signals to markets. Producers and consumers shift accordingly. Where they turn their gaze is not known with certainty.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Everyone wants to be unique. Elvis Costello made a career out of it. Costello’s biting sarcasm stood in stark contrast to the wave of conservatism that swept Britain in the late 1970’s and brought Margaret Thatcher to power. He might have been talking about the military, or he could have meant the anonymous office drones, or maybe he was thinking of the formulaic record company hit makers. Whomever it was – probably all the above – he knew he couldn’t be one of them.

You can be a non-conformist investor. The romantics believe that you will be paid quite handsomely like John Paulson or Michael Burry. Most of the time you end up underperforming. In the worst cases, you finish lonely and broke like Jesse Livermore.

I had aspirations of finding that iconoclastic piece of investing research when I sought to understand Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP). Just as I was about to hit send, I found a major bust in my numbers. To quote the legendary bassist Mike Watt:

After correcting the error, my valuation exercise resulted in a number that was pretty close to the current market price. There’s nothing particularly wrong with this conclusion. Most of the time, markets are efficient. However, I was convinced that Brookfield Infrastructure Partners was wildly overvalued. Confirmation bias can be a hell of a drug, apparently. So, here’s my story. If you stick around until the end, you just might find some loose threads to pull that may yet prove to be BIP’s Achilles heel.

When most people discuss Brookfield, they are either referring to the giant Canadian asset fund known as Brookfield Corporation (BN), with a market cap of $91 billion, or its cousin Brookfield Asset Management (BAM), with a market cap of $22.8 billion. I’m writing about another head of the hydra: Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP), the publicly traded limited partnership with a market capitalization of $13.64 billion at the recent price of $29.54 per unit.

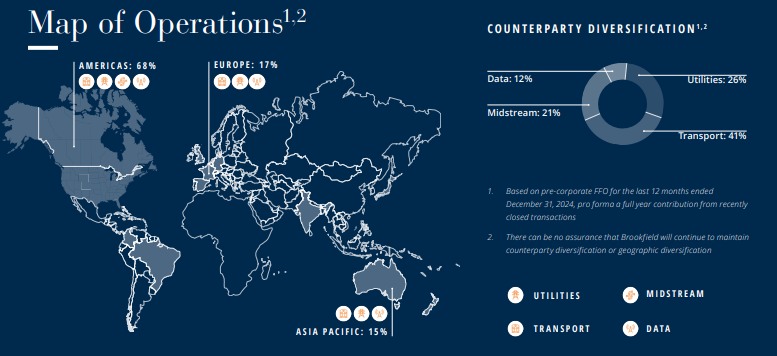

Brookfield Infrastructure Partners posted consolidated revenues of $21 billion in 2024 among four segments: utilities, transport, midstream and data. Utilities include 2,900 km of transmission lines in Brazil and 3,900 km of natural gas pipelines in North America, Brazil, and India. There’s also smaller distribution and metering businesses in the UK and ANZ. Transport includes the Triton intermodal container business, minor railroads in North America, Europe and Western Autralia, and toll roads in Brazil. Midstream is largely focused on gas pipelines and gas liquids processing facilities in North America (primarily operated by Inter Pipeline of Canada). The data business includes fiber optic networks in North America, Brazil, and Australia, 300,000 cell towers in Europe and India, and 140 data centers. There are no synergies between these businesses. It is largely a collection of assets gathered by Brookfield Corporation (BN), and Brookfield Asset Management (BAM) which generate significant management fees.

Deciphering BIP requires a compass and flashlight. The company is structured as a limited partnership with the controlling general partner (GP) interests held by a variety of Brookfield entities. Many entities are based offshore. Certain GP interests are also owned by the publicly traded Brookfield infrastructure Corporation (BIPC). The limited partnership units trade with the ticker BIP.

Consolidated assets of the holding company amounted to nearly $104.6 billion at the end of 2024. Debt totaled $54 billion. Book equity summed to $29.85 billion. Yet, the publicly traded limited partnership units have balance sheet equity of little more than $4.7 billion. Over $20.5 billion of book equity is attributable to joint venture partners and the balance of $4.6 billion is held by general partners and preferred interests.

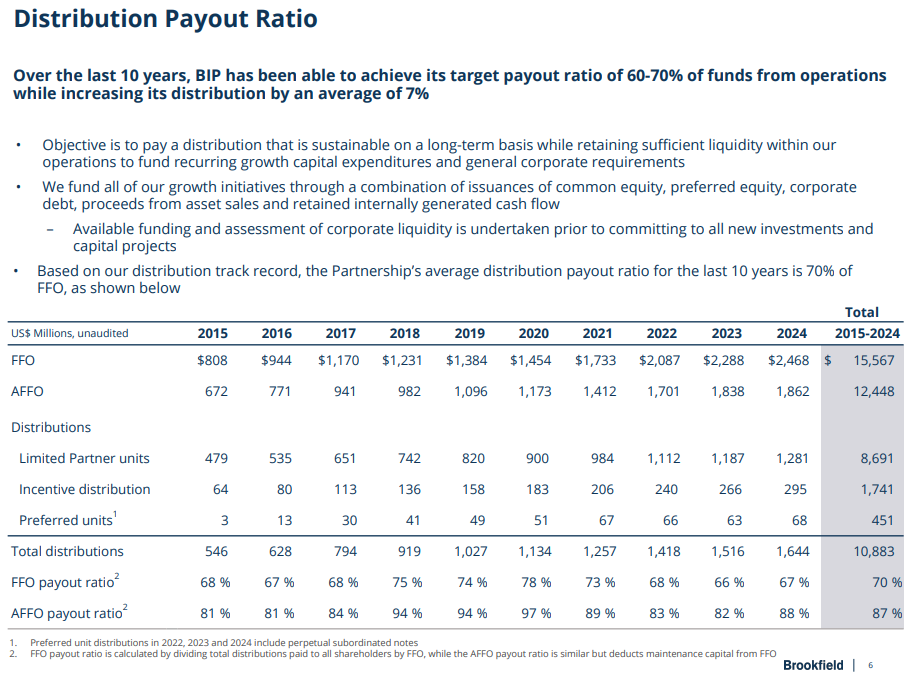

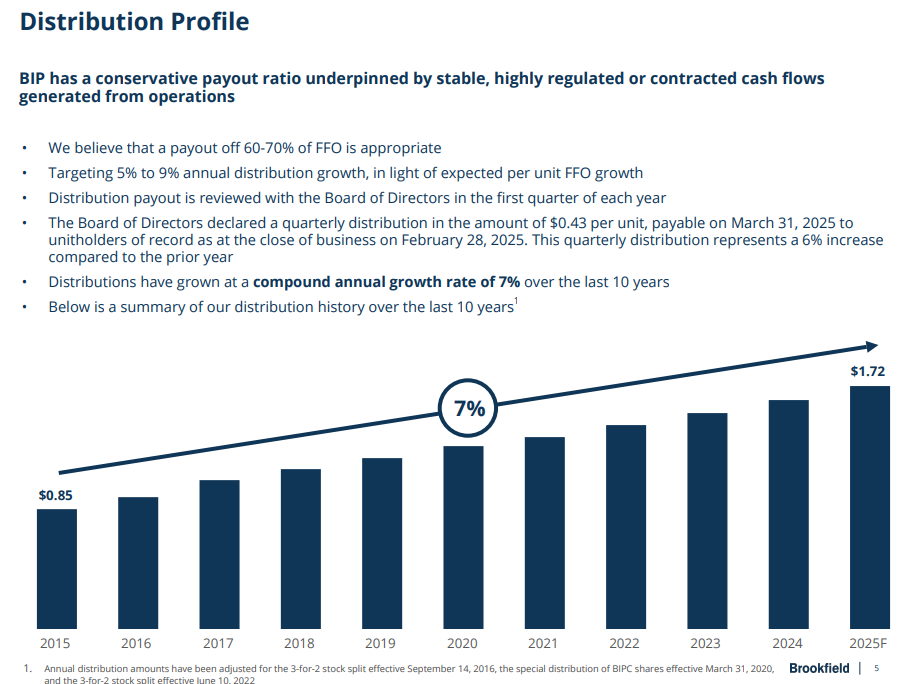

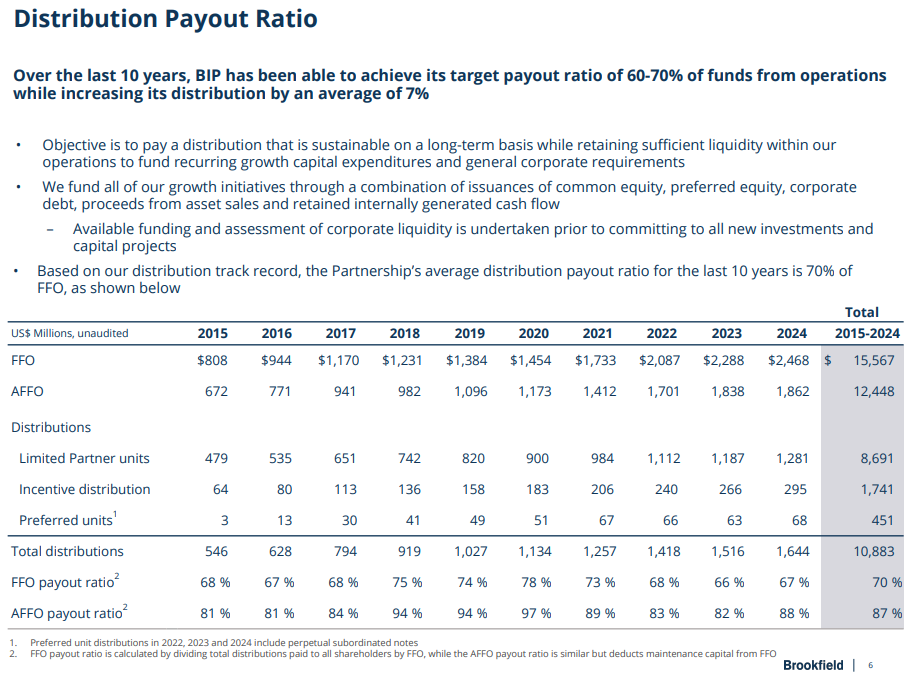

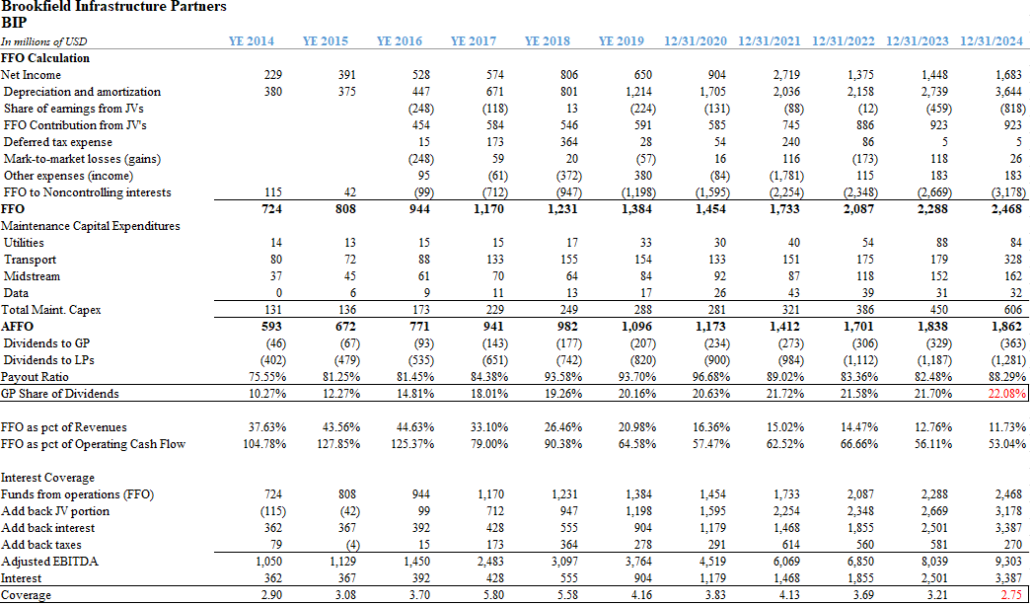

BIP is proud of its distributions to its limited partners. The dividend yield on offer for today’s unit purchasers is nearly 6%. According to BIP, this payout ratio is well-covered using the company’s preferred metric of distributions as a percentage of funds from operations (FFO), and as a percentage of adjusted funds from operations (AFFO). FFO is a proxy for operating cash flow. The measure adds non-cash items, mainly depreciation, back to net income. AFFO takes funds from operations and subtracts maintenance capital expenditures. According to BIP, 88% of AFFO is paid to partners. The dividend is a key component of BIPs investment appeal, and any doubt in the ability of the company to pay unitholders their quarterly stipend would surely send the share price plummeting.

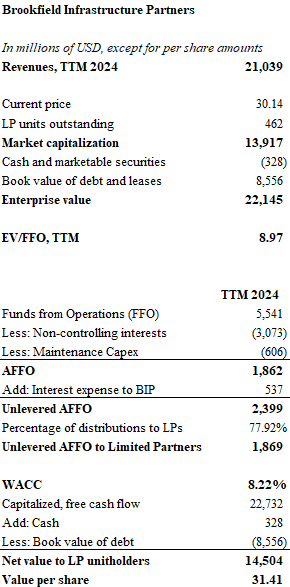

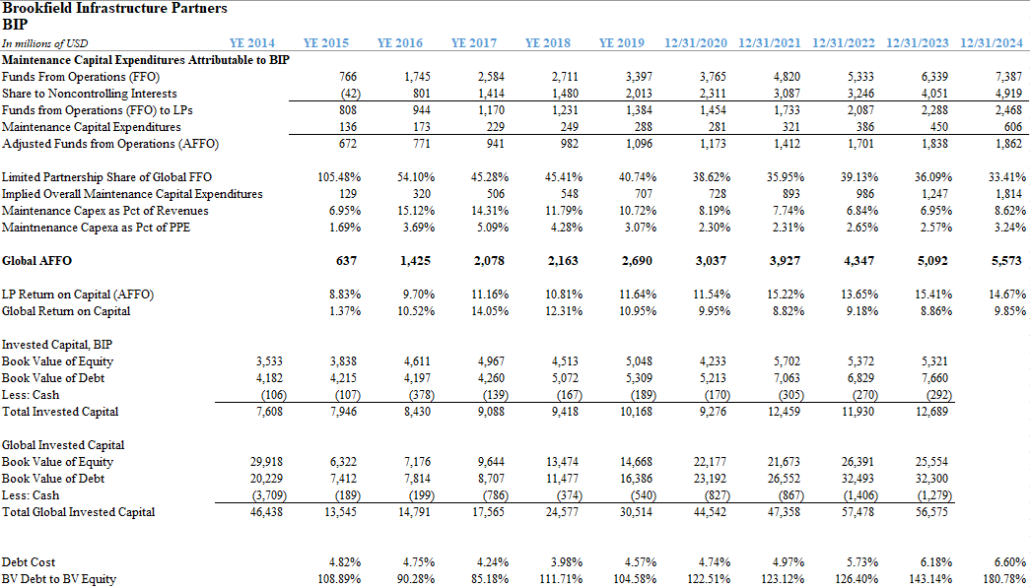

The most important conclusion to draw from the financial reports is just how little is owned by the limited partners. Publicly traded units of BIP only have a claim on 15.76% of the balance sheet equity. Funds from operations tell a similar story. Consolidated revenues of $21 billion emerge as $5.67 billion of FFO. Approximately $3.2 billion of FFO is attributable to the joint venture partners, leaving $2.47 billion of funds from operations attributable to the partnership. Next, BIP deducts maintenance capital expenditures of $606 million. This leaves $1.86 billion of adjusted funds from operations (AFFO). Limited partners received 77.9% of the distributions in 2024 and general partner and preferred interests received 22.1%.

Valuation

As noted above, BIP limited partners have a claim on approximately 15.76% of the company’s equity, so I adjusted balance sheet items to reflect this percentage. AFFO for 2024 was $1.86 billion. I added the proportional interest expense attributable to the partnership to arrive at an “unlevered AFFO” of $2.4 billion. Distributions were split between general partners and limited partners, with the LP’s receiving about 78% of the total. Therefore, I assigned $1.87 billion to the limited partners. This “unlevered AFFO to limited partners” was capitalized with by dividing the amount by 8.22%, the weighted average cost of capital for BIP.

Where does that 8.22% discount rate come from? At $8.5 billion, debt accounted for 39% of capital. Interest as a percentage of total financial liabilities cost BIP 6.28% in 2024, or 4.96% after tax deductibility is factored in. Equity costs take into account the geographic diversity of BIP’s revenues. The breakdown follows: 67% North America, 11% India, 12% South America, and 10% “Other”. I used the 10-year US Treasury rate of 4.31% for the risk-free rate assumption across all regions, but I did adjust the equity risk premiums. Therefore, the North American cost of equity is approximately 8.6%, India is 14.5% and Brazil is 15.3% the balance was weighted to a cost of equity of 10.2%. The total cost of equity amounted to 10.23%.

The total capitalized value to limited partners is $22.77 billion. After subtracting $8.3 billion of proportional net debt, the net value to the limited partner unitholders is $14.5 billion, or $31.41 per share. Based on this calculation, BIP is fairly valued.

It didn’t start out this way. I thought I would crunch enough numbers to show that Brookfield Infrastructure Partners is significantly overvalued.

My run down the rabbit hole started with an article which appeared in the Financial Times on March 5th. The article questioned the opaque financials of Brookfield Corporation (BN). In a series of transactions, Brookfield appeared to utilize reserves from its insurance subsidiaries to disguise losses on Manhattan office buildings. Casting doubt upon the integrity of one of the world’s largest asset managers is a tall order, so it raised a few eyebrows when the name Dan McCrum appeared in the byline. McCrum famously exposed the $24 billion Wirecard fraud in 2018. I’ve not read McCrum’s book about “Europe’s Enron”, but I highly recommend the documentary Skandal! in which he features prominently.

The FT article from March 5 quotes a few sources who share their skepticism about the Canadian asset management behemoth and its various holding companies and subsidiaries. One, Keith Dalrymple, has written several comprehensive pieces about Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP).

Dalrymple argues forcefully that the limited partnership units should trade for roughly net asset value. In his view, the market misunderstands the partnership to be a conglomerate with aggregated cash flows. In his view, BIP is merely an investment holding company which should be valued at the net value of its balance sheet. Dalrymple contends that BIP’s market value is overstated by as much as 300%.

There is no doubt that BIP’s use of consolidated financials allows the company to create the illusion of a unified conglomerate. Moreover, the liberal use of the non-GAAP accounting terms “FFO” and “AFFO” make the company sound like a real estate investment trust. The reality is far different. The web of joint ventures is a loose confederation of companies.

One of the most enlightening parts of Dalrymple’s research was his reference to Edper, a Canadian holding company that collapsed in 1995 under mountains of debt. At one point, Edper held assets of over $100 billion and employed over 100,000 Canadiens in its many subsidiaries. Its market capitalization once amounted to 15% of the Toronto Stock Exchange. Edper was the brainchild of Edward and Peter Bronfman. Exiled from the main Seagram’s Bronfman clan, Peter and Edward formed Edper in 1959. They controlled Trizec-Hahn, one of north America’s largest real estate developers, Brascan, the huge Canadian metals and mining giant, and Labatt Brewing. Control reached dozens of companies.

The brothers perfected the art of acquiring a business with borrowed money, taking most of it public while maintaining control, and using leverage to repeat the process over and over through a vast web of subsidiaries. Ultimately, excessive debt caused the empire to collapse. But the professional management at Edper didn’t disappear. In fact, EdperBrascan emerged from the ashes and changed its name to Brascan in 2000. It transformed itself into none other than Brookfield Asset Management in 2005.

Dalrymple contends that the modern Brookfield companies are using the same playbook. Looking at Brookfield Infrastructure Partners through the Edper lens changes one’s understanding of the limited partners: Although they are technically participants in the equity structure of the business, they have no voting authority. As long as BIP can pay the distributions, the units trade for a price that is three times as high as the value of its underlying assets. This expensive currency a useful tool for adding future joint ventures to the BIP umbrella.

In a sense, Brookfield is borrowing money at 6% interest under the guise of “equity”. It’s an especially good deal to be the general partner in this structure. After all, thanks to incentive payouts, general partners collected 22% of the distributions despite having a claim on less than 1% of book equity. Then there are the management fees. Brookfield earns 1.25% of the market value of all classes of partnership units plus recourse debt at the holding company level. Management fees were nearly $400 million in 2024. Add the $363 million of general partner distributions and you have proceeds to the parent companies that exceed 4% of revenues. This is a lucrative arrangement for BAM.

The area that bears further scrutiny is the use of maintenance capital expenditures to manage adjusted funds from operations. BIP reports that AFFO taken as a percentage of invested capital results in a return on capital between 14% and 15% over the past two years. I wanted to know if the overall company had equally stellar returns on capital. I decided to reverse engineer an FFO for the entire company. I took FFO attributable to the limited partnership and added back the FFO attributable to non-controlling interests. Let’s call this “global FFO”. Next, I took the percentage of limited partner FFO to global FFO for each year. Then I divided the maintenance capital expenditures attributed to the partnership by this percentage to come up with a “global maintenance capital expenditure” amount. Finally, I subtracted the global maintenance capital expenditures from the company wide consolidated FFO amount to calculate a “global AFFO” number. The return on capital was less than 10% on this company-wide basis.

I may be way out over my skis on this hypothesis, but one can envision a scenario where BIP maintains the illusion of strong performance by adjusting the maintenance capital expenditures in such a way to increase AFFO to the LP’s. The maintenance capital expenditure gray area could be rather fuzzy. How many accountants are questioning the useful life of a toll road in Minas Gerais, a cell tower in Kolkata, or a pipeline valve in Thunder Bay?

Finally, I would also highlight the growing weight of debt at the company. Leverage now exceeds 180% of book equity. Interest coverage defined as FFO-to-interest expense has steadily declined from over 5x in 2017 and 2018 to 2.75x last year. There’s plenty of coverage, but the margins are shrinking. Once again, the Edper playbook is at work. Not only is non-recourse debt present at the joint venture level, BIP has added $4.5 billion of corporate debt with no assets to back it up.

So where do we stand? Capitalizing unlevered AFFO gets you to a valuation in line with the current market price. This is reasonable, but its also the game that BIP management wants you to play. They want you to value the steady dividend and take their estimation of cash flows attributable to limited partners. A more cynical view is that the holding company is an illusion. The unified financial statements are possible because of intricate partnership control mechanisms. The company exists only on paper. The confederation of assets pay lucrative management fees, and as long as the dividend remains intact, few will question whether the company deserves to trade for three times its net book value.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.