Louis XIV was a control freak. The “Sun King” reigned from 1643 to 1715. The king’s day was timed to the minute to allow the officers in his service to plan their own work accordingly. From morning to evening his day ran like clockwork, to a schedule that was just as strictly ordered as life in the Court. “With an almanach and a watch, one could, from 300 leagues away, say with accuracy what he was doing”, wrote the Duke of Saint-Simon.

When it came to rigorous discipline, the King’s finance minister was equal to his master. The legendary Jean-Baptiste Colbert brought fiscal responsibility to a kingdom that was nearly bankrupt at the start of the 1650’s. Colbert, a relentless workaholic, introduced a system of government accounting that was the first of its kind. Spending was brought to heel and tax collections were enforced.

Colbert is often credited with laying the foundations of the modern French state. He centralized government power and introduced mercantilist policies which included investments in infrastructure and academies for the sciences, engineering and arts. Colbert raised tariffs on manufactured imports like Venetian glass and Dutch textiles and promoted French industry.

Although modern France recognizes Colbert’s fiscal innovations, few mourned his passing in 1683. The French taxation system was notoriously regressive, with nobles and clergy being exempt. Peasants, laborers and business owners were taxed heavily. Even many noblemen despaired at Colbert’s reforms. Oral testimony was no longer allowed for verification of one’s noble status. The rolls of noblemen were purged as those of the highest caste were required to provide documentary evidence dating back more than 100 years.

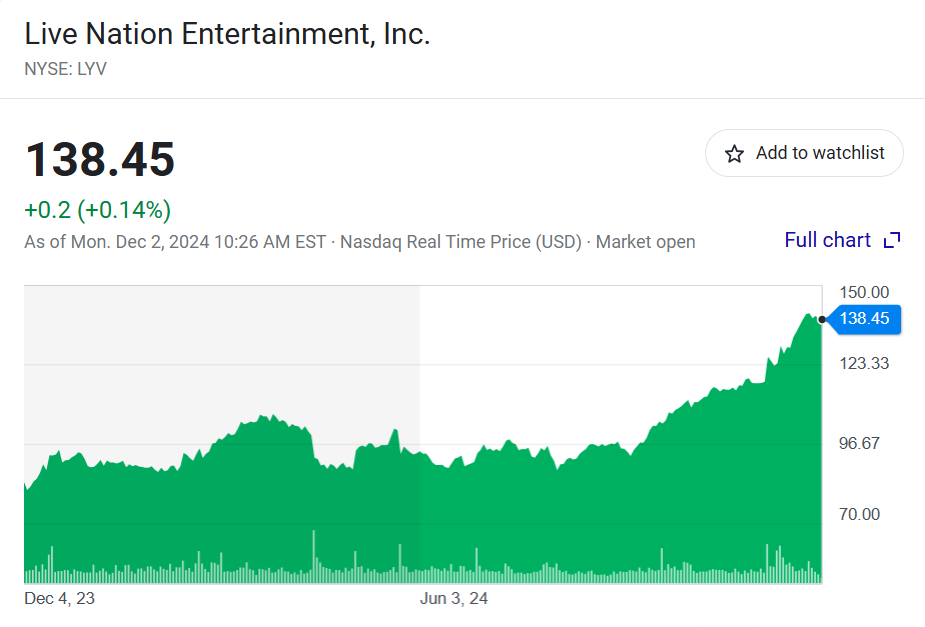

In modern finance, the lack of control can lead to all sorts of complications. Take Live Nation (LYV), for instance. Live Nation owns Ticketmaster and produces over 44,000 live music and events around the world each year. Yet, during the first nine months of 2024, only 60% of earnings were attributed to shareholders. The company owns and operates venues through a series of joint ventures with local promoters and facilities owners. These noncontrolling interests have a claim on 28% of net income.

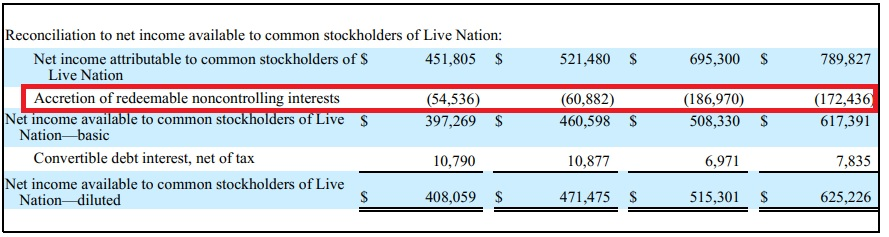

There are also redeemable noncontrolling interests that have a claim on company earnings. These are opaque arrangements with promoters that have the ability to sell their interests back to the parent company using a put option. The problem with these put options is that their costs are variable in nature – the more the company earns, the larger the option premium gets.

These redeemable noncontrolling interests are shown on the balance sheet as a liability, but because they can increase in value over time, this “accretion” is also deducted from earnings per share. For the nine-month period ending September 30, 2024, earnings amounted to $849.2 million. Subtract the share for noncontrolling interests, and $695.3 million was left. Or was it? Earnings per share should have been $2.95, but the accretion of redeemable noncontrolling interests for the period meant that only $2.18 was attributable to shareholders. This means that LYV is trading at 160 times earnings for the trailing 12-month period.

Live Nation seems to be overvalued by as much as 54% once deductions are made for noncontrolling interests. I am not even factoring in the possibility of anti-trust litigation for monopolizing the ticket industry. While such enforcement seems less likely under the Trump administration, much risk remains.

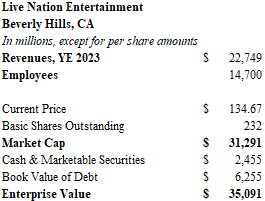

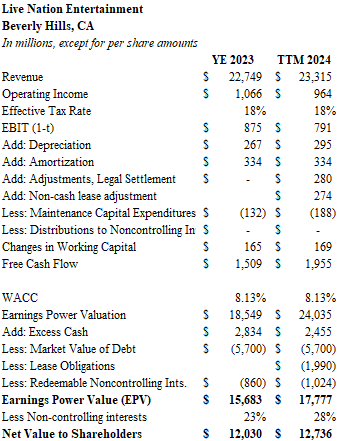

Live Nation posted $23.3 billion in revenues over the trailing twelve-month period. There are massive margins in tickets. Ticketing accounts for about 12% of revenues, and 37% of operating income. The venue operations, on the other hand, are capital intensive and only generate 5% margins. To make matters worse, growth seems to have peaked. With the conclusion of the Taylor Swift tour and the post-pandemic surge fading from view, revenues declined by over 6% in the third quarter. Aside from the excitement around the Sphere (SPHR) and a few major tours, many concerts have struggled over the past year.

Below is my earnings power valuation for Live Nation. I calculated an equity value of $12.7 billion versus the current market capitalization of $31.3 billion. I applied a weighted average cost of capital of 8.22%. This factor includes $6.3 billion of debt with an S&P rating of BB, or an imputed debt cost of 5.85% under current yields and spreads.

Is my discount rate too high? Perhaps. But even if you use 6%, the equity value sums to $18.8 billion. Should I factor in something for growth? Maybe. But there doesn’t seem to be much near-term growth. In the long-term, growth will come from more venue developments and leases – a business which generates poor yields on capital. There’s a reason why most venues are built with taxpayer funds: the economics rarely work. No amount of U2 and Adele concerts can save The Sphere from an eventual bankruptcy filing.

I am also being pretty fair with how I treat the redeemable noncontrolling interests. I do not deduct anything from earnings. Instead, I have deducted the $1 billion book value shown on the balance sheet after operating income has been capitalized. Finally, I only make a deduction for maintenance capital expenditures of $188 million. In reality, the future capital commitments for the firm are much greater.

It was said that between 3,000 and 10,000 courtiers visited Versailles on a daily basis for a chance to mingle with the Sun King. If only Colbert had Ticketmaster in his day.

Until next time.

The Seven Years’ War was the first global war. Battles were fought on three continents as European conflicts spread to colonial territories between 1754 and 1763. Great Britain and Prussia fought an alliance of France, Austria, Russia and Spain. In North America, Britain and France battled on the frontier. Iroquois warriors joined British soldiers against French forces allied with Algonquin and Huron tribes. In defeat, France ceded control of the Great Lakes and Canada.

The Seven Years’ War laid important foundations for the American Revolution. First, the war left Britain with heavy debts. Taxes were levied against the British colonies to replenish King George III’s treasury, sowing bitterness and resentment. Second, the war militarized the colonists. Militias were armed and George Washington and his officer peers trained under British high command. Third, France was eager to avenge her losses, and an alliance with the rebellious colonists would form in the following decade.

In the late days of the American Revolution, with Washington’s ragged army badly in need of a victory, France raised the game. Comte de Rochambeau marched 5,500 troops from Rhode Island to New York where the French Expédition Particulière joined the Continental Army. As French ships prevented a British escape from Chesapeake Bay, forces led by Washington, Lafayette and Rochambeau routed the redcoats at Yorktown, Virginia. The victory was decisive, and independence soon followed.

“Rochambeau” is instantly familiar to many because it is a name frequently given to the game more commonly known as “rock-paper-scissors”. You’ve never heard it called “Rochambeau” before? Me neither. But my friend from Colorado swears by it as does my native-Minnesotan wife.

Why Rochambeau? Was Lafayette the winner who laid some smooth paper on his compatriot’s rock, thus forcing Rochambeau to take command of a grueling march through the mid-Atlantic during the blistering humidity of a colonial summer? Paper always seems to be the sneakiest move. It’s counter-intuitive to win with paper, so light by nature, and it’s just the sort of play a sly bâtard like Lafayette would lay down. Touché.

It turns out there is no proof that Rochambeau ever played rock-paper-scissors, and drawing any connection with the French general is pure speculation. According to the authority on such matters, the World Rock-Paper-Scissors Association, the first mention of a game called Rochambeau appeared in the 1930’s.

Rochambeau is an easy game. Usually, the loser is required to complete some unpleasant obligations like take out the trash, change a diaper, follow Scooby into a haunted cave, or march to Yorktown through swamps and marshes. Government-sponored lotteries are also pretty simple. The winning number is drawn at random. Huge jackpots, microscopic odds. Our governments have been in the gambling business for a long time.

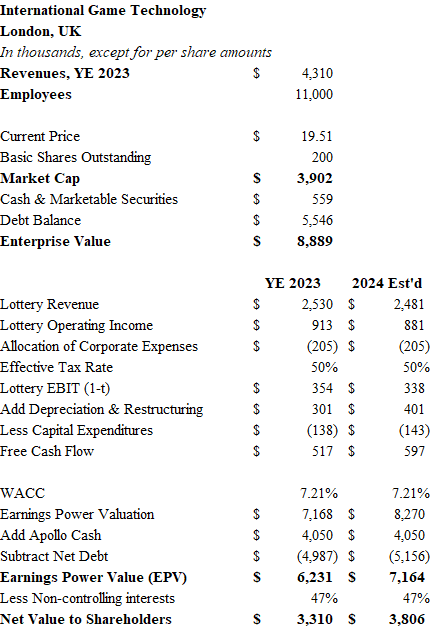

Governments sponsor and benefit from lotteries but they outsource the operations to businesses. The largest publicly traded provider of lottery services is a company called International Game Technology (IGT). Based in London, IGT has substantial operations in Italy and Rochambeau’s old stomping ground of Rhode Island. De Agostini, an Italian conglomerate, controls 42% of the company. IGT runs lotteries, and it also produces gambling technology and equipment. Earlier this year, private equity giant Apollo agreed to pay IGT $4.05 billion for the gaming division with plans to merge it with Everi – another game-tech business. The sale will be completed in the second half of 2025 and will leave IGT as purely a lottery service provider.

Unfortunately, there is no free lottery ticket lying on the ground for buyers of IGT. The price of IGT stock appears to offer no upside to those waiting for the check from Apollo to arrive. In fact, after adjusting for the Apollo transaction, the equity of the combined entity is trading at a 3% premium to the intrinsic value of the lottery business.

The lottery business may be appealing to some because it carries long-term contracts and largely predictable revenue streams. Although point-of-sale equipment is needed, the business doesn’t require a huge capital investment as more of it migrates online. But there lies part of the rub: as more moves online, the gambler’s options widen. Lotteries are a crude game of chance. Why not take a few hits at those wagers which involve “skill” – sports betting and casino games? Certainly, staid old lotteries will lose in the ever-increasing world of online gambling choices.

There are two other problems with IGT: One, the company provides a huge windfall for governments, so naturally it is taxed as such. Tax rates for the company approach 50%. Two, quite a lot of the profits go out the back door through a series of joint ventures. Non-controlling interests grab about 47% of the value.

So, what’s left for the shareholders? You’ve got a lottery business with $2.5 billion in revenues. Operating margins are about 27%, but the taxman taketh 50%. There is about $600 million of free cash flow remaining which can be capitalized at a rate of 7.2%*. Adding $4.05 billion of cash to the net debt of $5.16 billion, results in an equity value of $7.17 billion. Noncontrolling interests have a claim on 47%, so the lottery business is worth about $3.8 billion to shareholders. Meanwhile, the market cap of IGT equity is about $3.9 billion today.

Note: Between the time this article was drafted last week and published today, IGT dropped 6%.

IGT may be worth keeping an eye on. If the market continues to trade the business lower, a discount could emerge. Right now, the odds favor the house.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

*Weighted average cost of capital was determined with the assumption that the company’s optimal capitalization is 35% debt and 65% equity. IGT carries a BB+ S&P Rating and therefore has an approximate 6% cost of debt. The figure of 9.06% was calculated as the cost of equity.

Mauna Loa is Earth’s largest active volcano. The Hawaiian mountain is also the world’s tallest. Mauna Loa rises 30,085 feet from base to summit which is higher than Mount Everest measured from sea level to peak (29,029 feet). To say that much lies below the surface is an understatement. The weight of millions of years of volcanic eruptions has actually caused the Earth’s crust to sink by five miles. Therefore, the total height of Mauna Loa from the start of its eruptive history is an astounding 56,000 feet.

The 45,000 residents of Hilo, Hawaii, while living among some of the most beautiful surroundings in America, also face the possibility of extinction. Mauna Loa last erupted in 2022, but lava flows were minimal. Eruptions damaged small villages in 1926 and 1950. The most recent serious threat occurred in 1984, when massive rivers of molten rock stopped just a short distance from Hilo Bay. The threat to Hilo is not an apocalypse of Pompeian proportions. No, the real danger is a slow and painful demise. If Hilo Bay fills with lava, cargo ships can’t dock. The Big Island would cease to be habitable.

Now if you think I’m about to use my newfound knowledge of volcanic peril as some kind of metaphor for the current state of financial markets, you would be absolutely correct. It’s coming down Fifth Avenue. About as subtle as Captain Kirk wearing a Bill Cosby sweater.

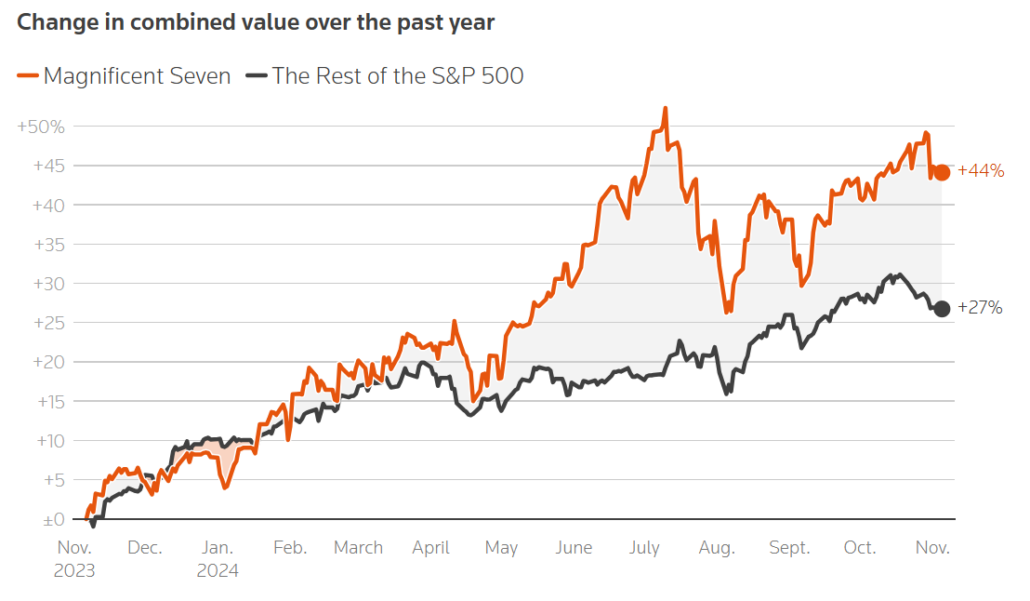

In my metaphor, Warren Buffett is the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. Vast, deep, and refreshingly cool with about $325 billion of cash on hand after selling more Apple stock, according to Saturday’s 3rd quarter report. Yes, he’s got some risk from storms but mostly it’s smooth sailing. Mauna Loa is the AI bubble. As lava keeps building up, the peak gets higher. It’s thrilling… and dangerous.

Technology companies will spend $200 billion this year on capital improvements related to artificial intelligence. This technology will require the addition of 14 gigawatts of additional power by 2030. To put that in perspective, Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s coal plant in Council Bluffs produces 1,600 megawatts of electricity.

Do you think nuclear is the solution? Well, Georgia just opened our country’s latest nuclear facility. The Alvin W. Vogtle Electrical Generating Plant sits along the Savannah River in Waynesboro. This marvel took 15 years to build and cost a mere $35 billion. Its generating capacity is 4,500 megawatts.

Technology has a history of delivering miracles, but it also bears witness to a poor track record of capital allocation. Look no further than Lumen Technologies (LUMN), the offspring of the fiber optic cable bubble of 1999-2001. Lumen holds the fiber assets of CenturyLink, Qwest and Level 3. If those names sound familiar, there was nothing like the Level 3 bubble for Omahans of a certain vintage who rode the Kiewit spinoff to dizzying heights and painful lows. And we all remember the Qwest Center. Despite a debt restructuring earlier this year, LUMN remains safely in junk territory and will be fortunate to stave off bankruptcy.

You didn’t come here for macro-economic observations or a mini-course in geography. There’s investment ideas to be had.

Welltower

My contention that Welltower remains 40% overpriced relative to the underlying value of its assets took a step back after the company raised annual per share FFO guidance to $4.33 from $4.20. In my estimation, this upgraded forecast is worth $1.3 billion of additional net asset value and raises the total to $50 billion. A nice boost, indeed. Shares rose accordingly.

Despite the improved performance, my bearish outlook for Welltower remains firmly intact. If you’re scoring at home, you’ve got a REIT with a market cap of $80 billion yielding less than 2% and trading at 30 times FFO. The company also announced a $5 billion equity offering. REITs like Welltower that invest capital at modest yields are forced to turn to equity for growth when the debt gets too expensive. They become dilution machines.

CK Hutchison

There are times when value traps are like a Siren’s song. It’s like watching Lethal Weapon when nothing else is on. You know that there is no plausible reason why Gary Busey’s henchmen can’t kill Danny Glover in the middle of the desert, but you’re damn well going to watch anyway because you need proof that this cinematic muddle was deserving of three sequels. But thank God they kept going! Lethal Weapon 2 has that fantastic moment when Joe Pesci brings Danny Glover to the South African consulate and tells them he wants to emigrate to the land of Apartheid.

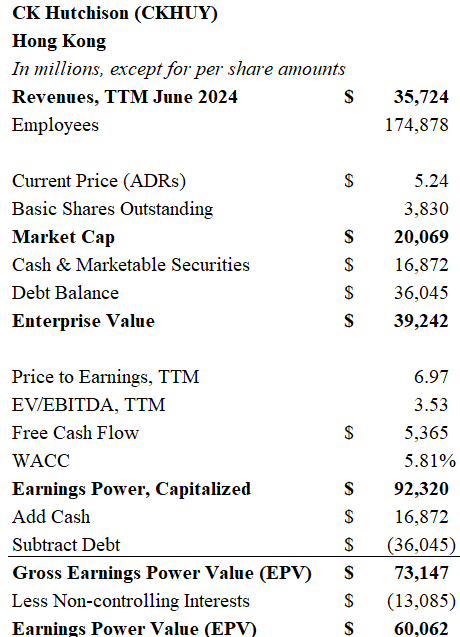

Anyway, CK Hutchison is the descendant of the Hutchison Whampoa conglomerate built over decades by Li Ka-Shing in Hong Kong. I wish there was an updated biography of Li who is now in his mid-nineties and has passed the reigns to his son. He certainly belongs in the business hall of fame. CK Hutchison has a market capitalization of about $20 billion and holds some of the world’s largest port infrastructure assets and telecom businesses. The stock trades at 29% of book value and offers a dividend yield of about 6%.

I ran a few back of the envelope numbers, and CK Hutchison pencils to roughly $60 billion of value. Yet, the stock has been “cheap” for many years. Why decide to invest now? It seems like the second generation of Li’s family (now in their 60’s) has figured out that something needs to be done for long-suffering investors. The company listed its infrastructure assets on the London exchange in August as “CK Infrastructure”. They have also contributed their European mobile networks to a joint venture with Vodafone.

The appeal of CK Hutchison is that its port infrastructure is irreplaceable. Unlike auto manufacturers and steel companies which deservedly trade below book value due to brutal competition, ports are generally impervious to competition. Nature only created so many locations around the globe where massive cargoes can dock. Globalization may be taking a step back, but it’s not stopping. I’m going to dig more deeply into CK Hutchison.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.