Everyone wants to be unique. Elvis Costello made a career out of it. Costello’s biting sarcasm stood in stark contrast to the wave of conservatism that swept Britain in the late 1970’s and brought Margaret Thatcher to power. He might have been talking about the military, or he could have meant the anonymous office drones, or maybe he was thinking of the formulaic record company hit makers. Whomever it was – probably all the above – he knew he couldn’t be one of them.

You can be a non-conformist investor. The romantics believe that you will be paid quite handsomely like John Paulson or Michael Burry. Most of the time you end up underperforming. In the worst cases, you finish lonely and broke like Jesse Livermore.

I had aspirations of finding that iconoclastic piece of investing research when I sought to understand Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP). Just as I was about to hit send, I found a major bust in my numbers. To quote the legendary bassist Mike Watt:

After correcting the error, my valuation exercise resulted in a number that was pretty close to the current market price. There’s nothing particularly wrong with this conclusion. Most of the time, markets are efficient. However, I was convinced that Brookfield Infrastructure Partners was wildly overvalued. Confirmation bias can be a hell of a drug, apparently. So, here’s my story. If you stick around until the end, you just might find some loose threads to pull that may yet prove to be BIP’s Achilles heel.

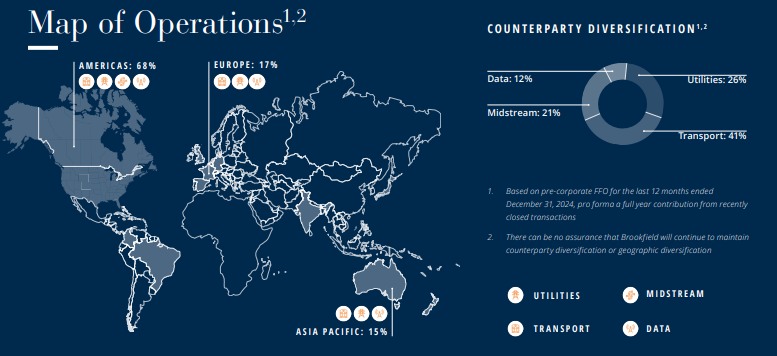

When most people discuss Brookfield, they are either referring to the giant Canadian asset fund known as Brookfield Corporation (BN), with a market cap of $91 billion, or its cousin Brookfield Asset Management (BAM), with a market cap of $22.8 billion. I’m writing about another head of the hydra: Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP), the publicly traded limited partnership with a market capitalization of $13.64 billion at the recent price of $29.54 per unit.

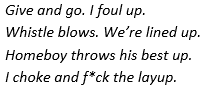

Brookfield Infrastructure Partners posted consolidated revenues of $21 billion in 2024 among four segments: utilities, transport, midstream and data. Utilities include 2,900 km of transmission lines in Brazil and 3,900 km of natural gas pipelines in North America, Brazil, and India. There’s also smaller distribution and metering businesses in the UK and ANZ. Transport includes the Triton intermodal container business, minor railroads in North America, Europe and Western Autralia, and toll roads in Brazil. Midstream is largely focused on gas pipelines and gas liquids processing facilities in North America (primarily operated by Inter Pipeline of Canada). The data business includes fiber optic networks in North America, Brazil, and Australia, 300,000 cell towers in Europe and India, and 140 data centers. There are no synergies between these businesses. It is largely a collection of assets gathered by Brookfield Corporation (BN), and Brookfield Asset Management (BAM) which generate significant management fees.

Deciphering BIP requires a compass and flashlight. The company is structured as a limited partnership with the controlling general partner (GP) interests held by a variety of Brookfield entities. Many entities are based offshore. Certain GP interests are also owned by the publicly traded Brookfield infrastructure Corporation (BIPC). The limited partnership units trade with the ticker BIP.

Consolidated assets of the holding company amounted to nearly $104.6 billion at the end of 2024. Debt totaled $54 billion. Book equity summed to $29.85 billion. Yet, the publicly traded limited partnership units have balance sheet equity of little more than $4.7 billion. Over $20.5 billion of book equity is attributable to joint venture partners and the balance of $4.6 billion is held by general partners and preferred interests.

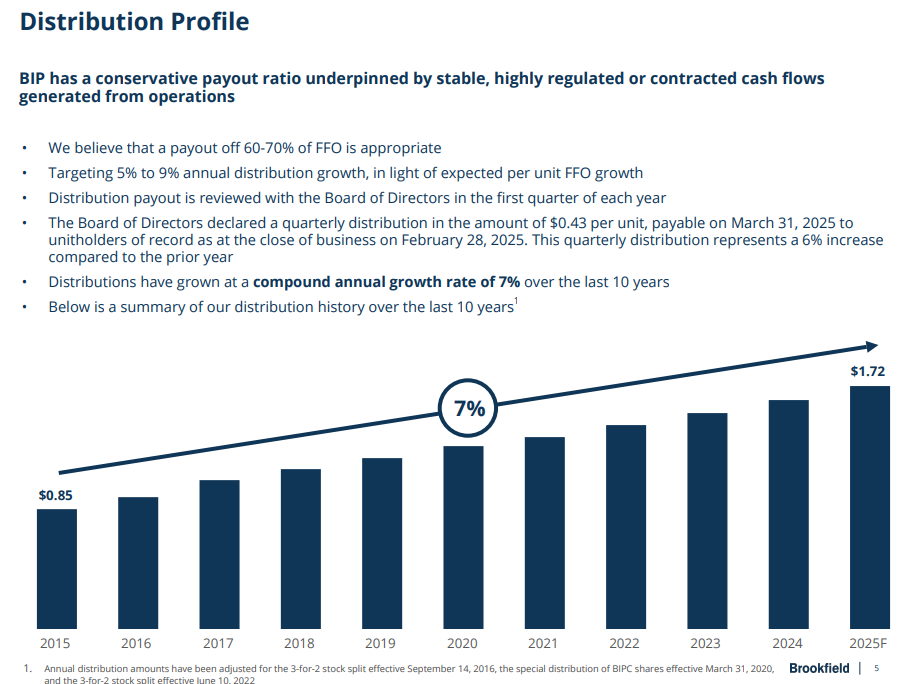

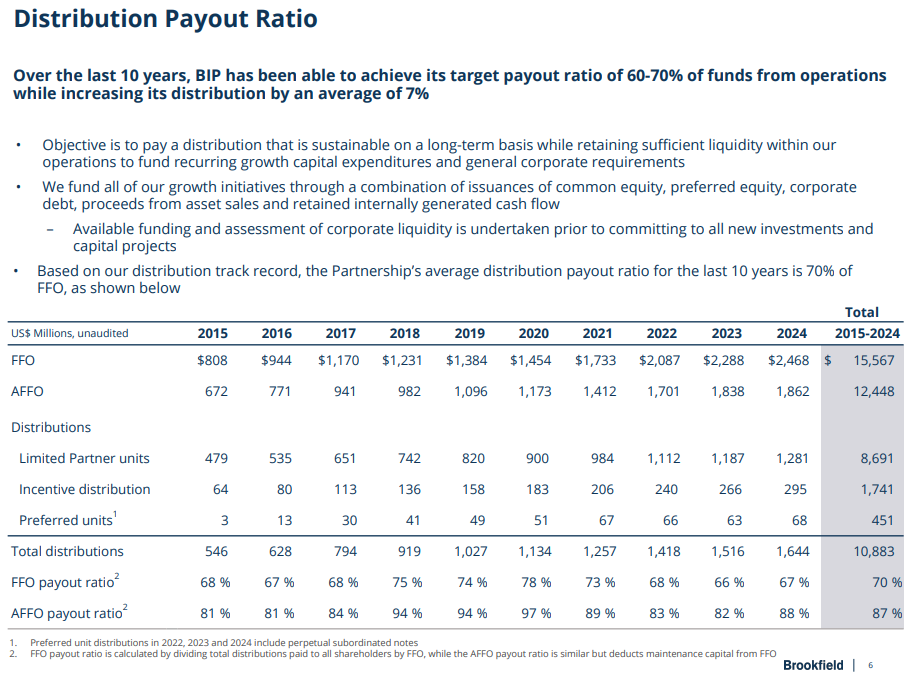

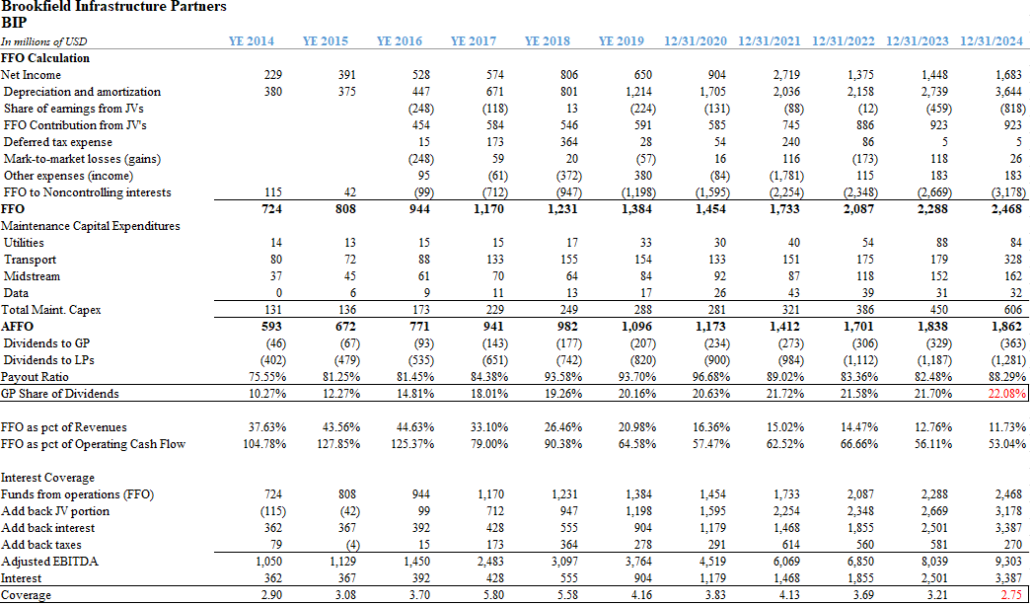

BIP is proud of its distributions to its limited partners. The dividend yield on offer for today’s unit purchasers is nearly 6%. According to BIP, this payout ratio is well-covered using the company’s preferred metric of distributions as a percentage of funds from operations (FFO), and as a percentage of adjusted funds from operations (AFFO). FFO is a proxy for operating cash flow. The measure adds non-cash items, mainly depreciation, back to net income. AFFO takes funds from operations and subtracts maintenance capital expenditures. According to BIP, 88% of AFFO is paid to partners. The dividend is a key component of BIPs investment appeal, and any doubt in the ability of the company to pay unitholders their quarterly stipend would surely send the share price plummeting.

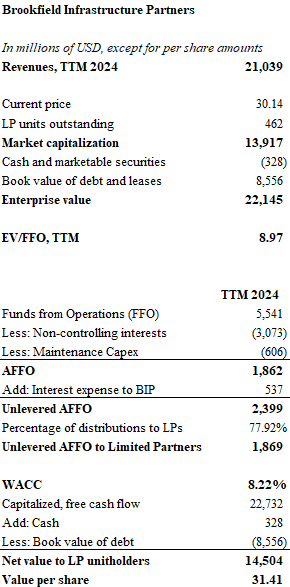

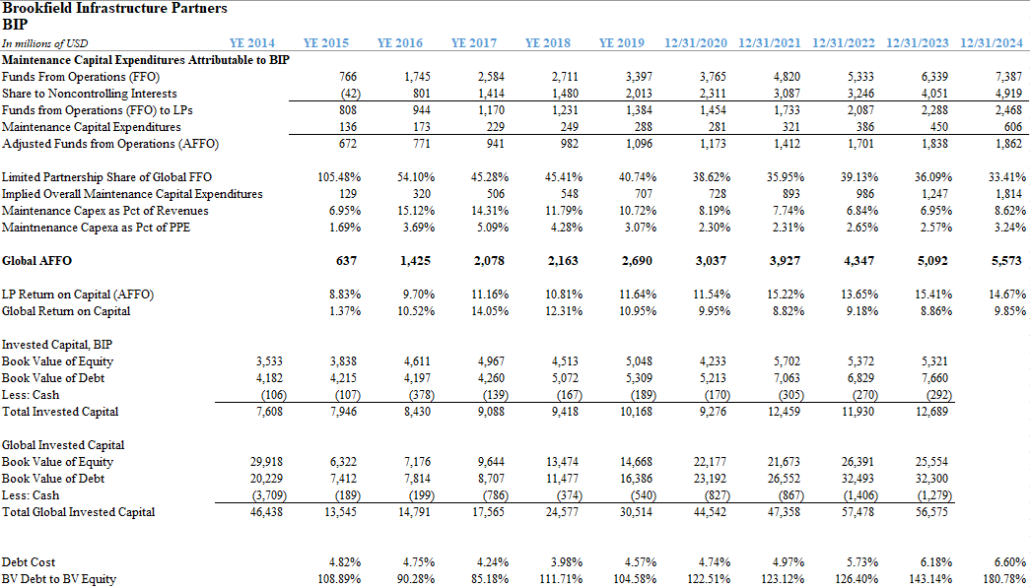

The most important conclusion to draw from the financial reports is just how little is owned by the limited partners. Publicly traded units of BIP only have a claim on 15.76% of the balance sheet equity. Funds from operations tell a similar story. Consolidated revenues of $21 billion emerge as $5.67 billion of FFO. Approximately $3.2 billion of FFO is attributable to the joint venture partners, leaving $2.47 billion of funds from operations attributable to the partnership. Next, BIP deducts maintenance capital expenditures of $606 million. This leaves $1.86 billion of adjusted funds from operations (AFFO). Limited partners received 77.9% of the distributions in 2024 and general partner and preferred interests received 22.1%.

Valuation

As noted above, BIP limited partners have a claim on approximately 15.76% of the company’s equity, so I adjusted balance sheet items to reflect this percentage. AFFO for 2024 was $1.86 billion. I added the proportional interest expense attributable to the partnership to arrive at an “unlevered AFFO” of $2.4 billion. Distributions were split between general partners and limited partners, with the LP’s receiving about 78% of the total. Therefore, I assigned $1.87 billion to the limited partners. This “unlevered AFFO to limited partners” was capitalized with by dividing the amount by 8.22%, the weighted average cost of capital for BIP.

Where does that 8.22% discount rate come from? At $8.5 billion, debt accounted for 39% of capital. Interest as a percentage of total financial liabilities cost BIP 6.28% in 2024, or 4.96% after tax deductibility is factored in. Equity costs take into account the geographic diversity of BIP’s revenues. The breakdown follows: 67% North America, 11% India, 12% South America, and 10% “Other”. I used the 10-year US Treasury rate of 4.31% for the risk-free rate assumption across all regions, but I did adjust the equity risk premiums. Therefore, the North American cost of equity is approximately 8.6%, India is 14.5% and Brazil is 15.3% the balance was weighted to a cost of equity of 10.2%. The total cost of equity amounted to 10.23%.

The total capitalized value to limited partners is $22.77 billion. After subtracting $8.3 billion of proportional net debt, the net value to the limited partner unitholders is $14.5 billion, or $31.41 per share. Based on this calculation, BIP is fairly valued.

It didn’t start out this way. I thought I would crunch enough numbers to show that Brookfield Infrastructure Partners is significantly overvalued.

My run down the rabbit hole started with an article which appeared in the Financial Times on March 5th. The article questioned the opaque financials of Brookfield Corporation (BN). In a series of transactions, Brookfield appeared to utilize reserves from its insurance subsidiaries to disguise losses on Manhattan office buildings. Casting doubt upon the integrity of one of the world’s largest asset managers is a tall order, so it raised a few eyebrows when the name Dan McCrum appeared in the byline. McCrum famously exposed the $24 billion Wirecard fraud in 2018. I’ve not read McCrum’s book about “Europe’s Enron”, but I highly recommend the documentary Skandal! in which he features prominently.

The FT article from March 5 quotes a few sources who share their skepticism about the Canadian asset management behemoth and its various holding companies and subsidiaries. One, Keith Dalrymple, has written several comprehensive pieces about Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP).

Dalrymple argues forcefully that the limited partnership units should trade for roughly net asset value. In his view, the market misunderstands the partnership to be a conglomerate with aggregated cash flows. In his view, BIP is merely an investment holding company which should be valued at the net value of its balance sheet. Dalrymple contends that BIP’s market value is overstated by as much as 300%.

There is no doubt that BIP’s use of consolidated financials allows the company to create the illusion of a unified conglomerate. Moreover, the liberal use of the non-GAAP accounting terms “FFO” and “AFFO” make the company sound like a real estate investment trust. The reality is far different. The web of joint ventures is a loose confederation of companies.

One of the most enlightening parts of Dalrymple’s research was his reference to Edper, a Canadian holding company that collapsed in 1995 under mountains of debt. At one point, Edper held assets of over $100 billion and employed over 100,000 Canadiens in its many subsidiaries. Its market capitalization once amounted to 15% of the Toronto Stock Exchange. Edper was the brainchild of Edward and Peter Bronfman. Exiled from the main Seagram’s Bronfman clan, Peter and Edward formed Edper in 1959. They controlled Trizec-Hahn, one of north America’s largest real estate developers, Brascan, the huge Canadian metals and mining giant, and Labatt Brewing. Control reached dozens of companies.

The brothers perfected the art of acquiring a business with borrowed money, taking most of it public while maintaining control, and using leverage to repeat the process over and over through a vast web of subsidiaries. Ultimately, excessive debt caused the empire to collapse. But the professional management at Edper didn’t disappear. In fact, EdperBrascan emerged from the ashes and changed its name to Brascan in 2000. It transformed itself into none other than Brookfield Asset Management in 2005.

Dalrymple contends that the modern Brookfield companies are using the same playbook. Looking at Brookfield Infrastructure Partners through the Edper lens changes one’s understanding of the limited partners: Although they are technically participants in the equity structure of the business, they have no voting authority. As long as BIP can pay the distributions, the units trade for a price that is three times as high as the value of its underlying assets. This expensive currency a useful tool for adding future joint ventures to the BIP umbrella.

In a sense, Brookfield is borrowing money at 6% interest under the guise of “equity”. It’s an especially good deal to be the general partner in this structure. After all, thanks to incentive payouts, general partners collected 22% of the distributions despite having a claim on less than 1% of book equity. Then there are the management fees. Brookfield earns 1.25% of the market value of all classes of partnership units plus recourse debt at the holding company level. Management fees were nearly $400 million in 2024. Add the $363 million of general partner distributions and you have proceeds to the parent companies that exceed 4% of revenues. This is a lucrative arrangement for BAM.

The area that bears further scrutiny is the use of maintenance capital expenditures to manage adjusted funds from operations. BIP reports that AFFO taken as a percentage of invested capital results in a return on capital between 14% and 15% over the past two years. I wanted to know if the overall company had equally stellar returns on capital. I decided to reverse engineer an FFO for the entire company. I took FFO attributable to the limited partnership and added back the FFO attributable to non-controlling interests. Let’s call this “global FFO”. Next, I took the percentage of limited partner FFO to global FFO for each year. Then I divided the maintenance capital expenditures attributed to the partnership by this percentage to come up with a “global maintenance capital expenditure” amount. Finally, I subtracted the global maintenance capital expenditures from the company wide consolidated FFO amount to calculate a “global AFFO” number. The return on capital was less than 10% on this company-wide basis.

I may be way out over my skis on this hypothesis, but one can envision a scenario where BIP maintains the illusion of strong performance by adjusting the maintenance capital expenditures in such a way to increase AFFO to the LP’s. The maintenance capital expenditure gray area could be rather fuzzy. How many accountants are questioning the useful life of a toll road in Minas Gerais, a cell tower in Kolkata, or a pipeline valve in Thunder Bay?

Finally, I would also highlight the growing weight of debt at the company. Leverage now exceeds 180% of book equity. Interest coverage defined as FFO-to-interest expense has steadily declined from over 5x in 2017 and 2018 to 2.75x last year. There’s plenty of coverage, but the margins are shrinking. Once again, the Edper playbook is at work. Not only is non-recourse debt present at the joint venture level, BIP has added $4.5 billion of corporate debt with no assets to back it up.

So where do we stand? Capitalizing unlevered AFFO gets you to a valuation in line with the current market price. This is reasonable, but its also the game that BIP management wants you to play. They want you to value the steady dividend and take their estimation of cash flows attributable to limited partners. A more cynical view is that the holding company is an illusion. The unified financial statements are possible because of intricate partnership control mechanisms. The company exists only on paper. The confederation of assets pay lucrative management fees, and as long as the dividend remains intact, few will question whether the company deserves to trade for three times its net book value.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

I decided I needed a soundtrack for this week’s article. The theme is regret – the feeling that you wish you could change something that’s already happened. Edith Piaf laid the mark down. She had no regrets at all. Defiantly, she announced:

Je repars á zéro. Non, rien de rien. Non, je ne regrette rien!

Non, je ne regrette rien (No, I Regret Nothing) topped French charts for seven weeks in 1960 and became more famous for its use in countless movies since. Edith is musical tonic for the gin of regret. Still feeling guilty about that nice guy you ghosted after you found out he owned six cats? Edith at full blast will fix that.

Need a song that shows a little remorse, but still basically says “f*ck ’em”? Leave it to Ol’ Blue Eyes. In 1969, Frank Sinatra crooned with feigned modesty:

Regrets, I’ve had a few. But then again, too few to mention… And more, much more than this, I did it my way.

Artists were more introspective in the post-Vietnam era. Regret began to fill the airwaves. Take the easy-going beach classic Margaritaville by Jimmy Buffett. The 1977 ballad seems innocuous on the surface. Tequila, salt, sand and sun. But don’t let those steel drums fool you. Margaritaville, the anthem for an entire cult following, is all about regret. Jimmy Buffett is basically drowning his sorrows because he knows he blew his chance at true love.

I know it’s my own damn fault.

By the 1990’s, Regret was on full display. All Apologies by Nirvana immediately comes to mind, but I prefer Pearl Jam’s Black for its gut-wrenching agony.

I know someday you’ll have a beautiful life. I know you’ll be a star in somebody else’s sky. But why, why can’t it be. Oh, can’t it be mine?

Need more? Johnny Cash covered Trent Reznor’s Hurt:

If I could start again. A million miles away. I would keep myself. I would find a way.

That’s some painful regret right there. If you’re reaching for the tissues, let’s close our little musical journey on a lighter note. Taylor Swift’s, Back to December:

It turns out freedom ain’t nothing but missing you.

Ah, that’s better.

Regret is a dish served cold in Leverkusen, Germany. If you call Bayer headquarters and get placed on hold, you probably have to listen to Radiohead. The regret of which I speak is the 2018 purchase of Monsanto for $63 billion. It has been nothing short of a disaster for the venerable aspirin-maker which dates its founding to 1863.

Bayer operates in three segments: Crop Science (2024 revenues, €22.3 billion), Pharmaceuticals (€18.1 billion), and Consumer Health (€5.9 billion). Crop Science features the RoundUp herbicide franchise and DeKalb seeds. Pharmaceuticals offer a wide range of treatments with success in cardiology and women’s health. Consumer Health includes the famous Aspirin brand as well as Aleve, Claritin, MiraLax, and AlkaSeltzer.

The Crop Science business presents the largest challenge. Between 2019 and 2024, Bayer has taken over $13 billion in goodwill impairment charges. The company has accumulated over $19 billion for litigation expenses. The problem has been claims that RoundUp, the indispensable weed-killer, causes cancer. Monsanto has reached settlement agreements on nearly 100,000 lawsuits for approximately $11 billion and estimates that 58,000 cases remain. However, Bayer won a significant victory last August when the US Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Federal law shields the company from claims at the state level. The court rejected a plaintiff’s claim that Monsanto placed farmers in danger by failing to place a cancer warning label on the product. The ruling conflicts with other decisions and leads to a belief that the commerce-friendly US Supreme Court could soon weigh in and reduce Bayer’s liabilities.

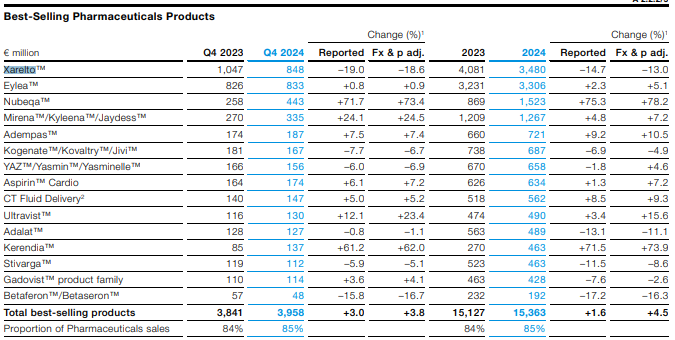

The Pharmaceutical division faces an urgent need to replenish its drug pipeline. Xarelto is Bayer’s bestselling drug, but its patent expired in 2024. Generics have started to cut into sales of the anti-coagulant. Xarelto sales topped $4 billion in 2023 and declined to $3.5 billion in 2024. The top 15 medicines accounted for $15.3 billion of sales, or 85% of the pharmaceutical segment. The next best performer is Eylea at $3.3 billion and 1% annual growth, and Nubeqa at $1.5 billion and 73% annual growth. The drugs are for retinal diseases and cancer treatment, respectively. Only a German company could withstand the irony of producing medicines to cure cancer while simultaneously making a herbicide that is a carcinogen. Somewhere, Friedrich Nietzsche is having a laugh.

Bayer has two missions: clean up the Monsanto litigation and create a more robust pipeline of pharmaceuticals. Bill Anderson, a native Texan, was hired in 2023 to lead Bayer. Anderson is a drug industry veteran, having previously run Genentech’s oncology, immunology and opthamology divisions. He later served as CEO of Genentech, a subsidiary of the Swiss drug-giant Roche, and ultimately ran Roche’s entire pharmaceuticals division. Given Anderson’s background expertise, there is speculation that once the RoundUp litigation has been arrested, the crop sciences business could be sold.

What we need to know is whether or not Bayer has the makings of a good value investment. For all of Bayer’s problems, this is still a multinational company that generated $4.5 billion of free cash flow in 2024. If you can handle the rocky ride ahead, Bayer could prove to be a very lucrative investment with a great deal of upside.

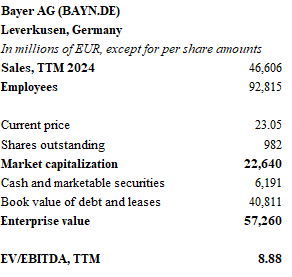

Shares trade on the DAX for about €23, giving the company a market capitalization of €22.6 billion, or $24.5 billion. American investors can buy ADRs with the BAYRY ticker for about $6.30 apiece. The company recently closed the books for 2024 and posted €46.6 billion of revenues, a decline of 9% from 2023. Operating income was €3.5 billion, with operating margins collapsing from 17.2% in 2023 to just below 7.5% in 2024. Mr. Anderson faces a stiff test.

Leverage is a concern. Over €40.8 billion of debt and leases weigh heavily. The board responded to the threat of losing Bayer’s BBB rating by eliminating the company’s hefty dividend which preserved about $2.4 billion last year. Debt was reduced from 2023’s level of $45 billion and is now on par with 2018 levels. Management is keen to reduce the debt further.

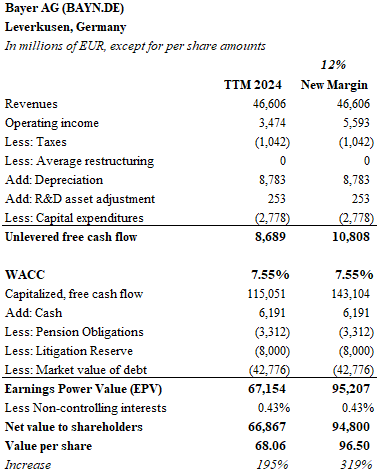

I decided to value Bayer using the preferred tool in Bruce Greenwald’s kit – a calculation of earnings power value (EPV) by taking normalized and unlevered free cash flow and dividing it by a percentage rate which reflects the company’s cost of capital. Using 2024 numbers, I calculated Bayer’s intrinsic value to be approximately €68 per share, or nearly three times its current trading price.

There are three items of note: First, I capitalized Bayer’s annual R&D spending which has hovered between €5 and €7 billion per year. The adjustment adds about €250 million to the annual income. Second, I made the computation of the weighted average cost of capital with a sledgehammer rather than a scalpel. Debt is fairly straightforward. As a BBB rated company, Bayer can borrow at 5.7% in the US market. I chose the US risk-free rate rather than the German bund rate that is about 150 basis points lower. For the equity (35% weight), I employed a 10% risk premium over our 10-Year rate, for 14.3%. The WACC, therefore, computes to 7.55%. Third, I deducted €8 billion from the value as a litigation reserve for future RoundUp claims.

Unlevered free cash flow of €8.7 billion is thus capitalized to €115 billion. Subtract net debt of €36.6 billion, pension obligations of €3.3 billion and the aforementioned litigation reserve, and the net value sums to €66.9 billion after a small adjustment for noncontrolling interests. The resulting share price of €68 gives an investor a very wide margin of safety.

Next, I made an assumption that Anderson and Co. can improve margins. Even if they rise to just 12%, still well below the recent past, it produces an additional €2.2 billion of operating cash. This boosts the share price above €96. One may quickly rebut my thesis by pointing out that the company very well may need every scrap of operating leverage if the Xarelto decline is more precipitous than expected, or the drug pipeline runneth dry.

The next exercise is to break down what a split-up Bayer might look like. Here’s a preview: The Crop Science business had an adjusted EBITDA of $4.3 billion in 2024. Corteva, spun off from DuPont in 2019 has a market cap of $41.5 billion and an EV/EBITDA multiple of 15. Even a 12 multiple would value Bayer’s agriculture division at €51.6 billion. Something to ponder.

Litigation is no way to run a business. If an investment thesis relies on a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court, you’re already on shaky ground. But Monsanto’s RoundUp isn’t like tobacco. It’s not a leisure product. RoundUp is an essential tool for the farming industry. Glyphosate is so effective, many farmers fear that it may disappear from the market and lead to replacement by cheap knock-offs from China which are likely to be unregulated and riskier to one’s health. RoundUp is not going away.

Things are looking better in Leverkusen. Even their fußball team, Bayer Leverkusen won the Bundesliga in 2024. It’s the first time a team other than Bayern Munich or Dortmund won since 2008. So, they’ve got that going for them, which is nice.

Hat tip to my friend Guillermo who hails from Vigo, Spain and put me onto the Bayer value story. Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

Boston real estate was feeling pretty sore in the early 1990’s. Many state-chartered banks in New England had collapsed under the weight of so many bad commercial real estate loans, just like their savings and loan brethren throughout the southwest. I first stepped into this troubled market by briefly working for a small real estate brokerage office in Boston.

We got a call from a man who was interested in selling his retail condominium. Wearing my coat and tie, I went with Peter, whom I considered a grizzled veteran even though he was probably only around 35. I didn’t even know about the existence of commercial condominiums. It was a first-floor space in a 1920’s brick building with large glass display windows. Despite the architectural charms, we didn’t think there was much of a market for a 2,500 square foot storefront with on-street parking.

The door opened with a jingle. Wood floors, high tin ceilings, and old brass lamp fixtures illuminated the room. The smell hit you right away. A sharp odor. Turpentine. Acetone. Oil. But it slowly faded into warm woodiness. Like an old church reassuringly scrubbed by parish ladies bearing buckets of Murphy’s oil soap and tins of carnuba wax.

We were met by the owner – a man who was probably in his early fifties, slim and athletic. He had wiry gray hair, sharp blue eyes and the kind of wrinkles you see on runners who have spent a lot of time in the sun. We reached out to shake hands and were clumsily met by his left which he cupped around the knuckles of our outstretched rights. I tried not to look too closely, but his right hand hung limply at his side.

After the awkward introduction, we soon realized we had entered the man’s cathedral. Before us stood row after row of heavy wooden desks – maybe 20 in all. Each one was a masterpiece of carved rosettes, scrolls, leaves, vines and columns. Mahogany pantheons stood among castles of walnut and majestic oak temples. Weighing hundreds of pounds, and much more expensive than any commission check that we stood to earn from a sale, these furnishings were destined for Back Bay mansions and State Street banks.

We learned the owner had suffered an accident on his bike that caused paralysis in his right arm. His career as a carpenter and craftsman was over. He had no partner or apprentice, and his children had moved on. He answered our real estate questions with grim stoicism, but his eyes sparkled once we asked him to show us his inventory. Was he at peace with his tragic misfortune? We took down his information, made some measurements and told him we would call with a proposal to list the space for sale.

I remember buckling the seatbelt when we got in Peter’s car. A small voice inside of me told me to go back and ask the man to teach me to continue his business. I could be his apprentice. This urge came despite my entire woodworking experience consisting of a single semester of shop class in seventh grade. He may have been flattered by my offer, but he would surely know his craft was more than a skill to be taught. It was art. Was I an artist?

As you grow older, you begin to wonder how different your life might have been if you had chosen different forks in the road. The furniture would have been magnificent. The finished product something to behold. Maybe I’d be the one looking for a woodworking apprentice today. Someone to carry on my craft.

Then you realize that every path is painful. How many desks could I have sold, really? All those hours sanding, carving, chiseling, and finishing. The dust, fumes, and bloodied fingers. The greedy lumber mill, the client’s bounced check, the revival of midcentury modern and Restoration Hardware. There’s no easy path, as fanciful as it may seem. Yet it was art. Something tangible. Not just numbers on a spreadsheet.

Ah well, off to the spreadsheets we go.

Elliott Management has received much notoriety for its activist shareholder campaigns. In recent weeks Paul Singer’s fund has taken large stakes in BP, Phillips 66, Honeywell, and Southwest Airlines (LUV). Although the firm chalked up a big win at Starbucks last year, two campaigns were less successful: A 2023 shake-up at Goodyear yielded no investment gains. Meanwhile, shares of Sensata (ST) have fallen 12% after an initial surge during May 2024’s announcement of a cooperation agreement between management and the fearsome investment firm. Elliott gained a board seat and pressed for the replacement of the CEO after a series of acquisitions that failed to deliver positive results.

I enjoyed some investment success several years ago when Elliott pressured Cabela’s to sell to Bass Pro Shops, so I am always tempted to follow Singer’s moves. Sensata trades 32% below its 52-week high, and it caught my eye. Goodyear turned out to be a rare blemish for the Elliott team. The tire business is plagued by shrinking margins and brutal competition from Asian manufacturers. Sensata is different. Sensata produces sensors and electrical protection components that have unique technological sophistication. Moreover, the adoption of hybrid and electric vehicles has increased demand for Sensata’s products.

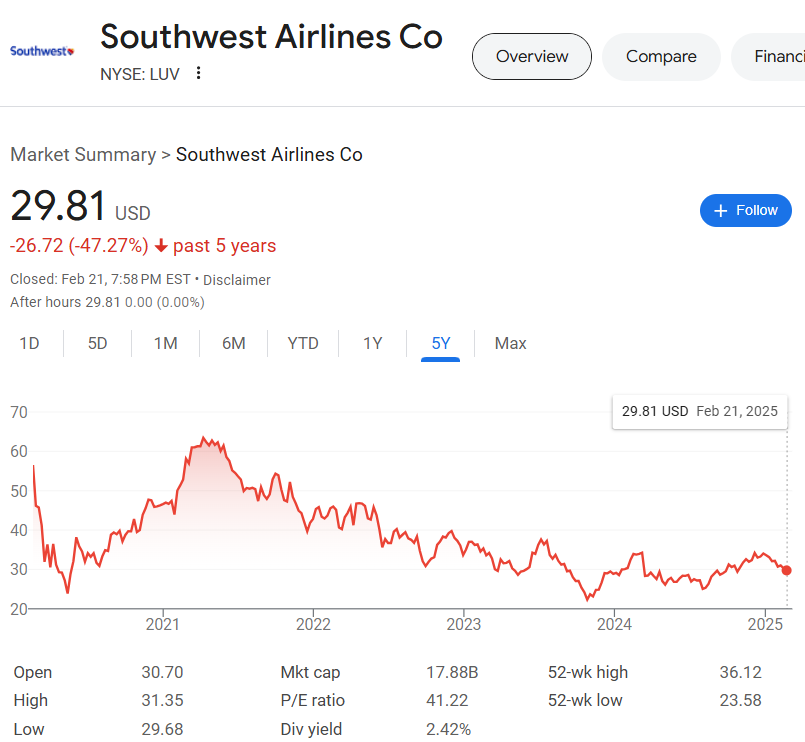

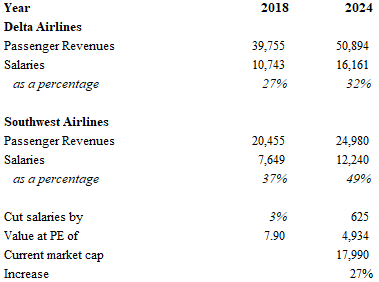

How will Elliott’s scheme play out? For my valuation exercise, I’m purely focused on the possibility of improved operating margins. This is Elliott’s playbook for Southwest. Last week, Southwest announced that they would conduct the first major layoff in the company’s history. They expect to cut salaries, primarily in the corporate offices, by 15%. This is part of an effort to save $500 million annually by 2027. Comparing salary margins at Southwest versus Delta Airlines, it’s not hard to see where value can be created.

Looking back to the peak of Southwest’s market capitalization in 2018, salaries accounted for 37% of passenger revenues. Meanwhile, salaries at Delta amounted to 27% of passenger revenues. Six years later, Delta’s wage bill has risen to 32% and Southwest’s surged to 49%. There’s no argument to be made that Southwest can match Delta. But can they cut salaries back to 46% of passenger revenues? That seems very likely. Such a reduction would boost profits at Southwest by $625 million. Assuming a post-tax multiple of 7.9x translates into $5 billion of market capitalization for LUV, or just about 27% above current levels.

How about Sensata? What kind of value creation can margin improvement deliver?

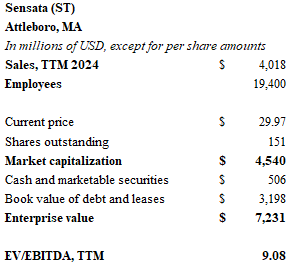

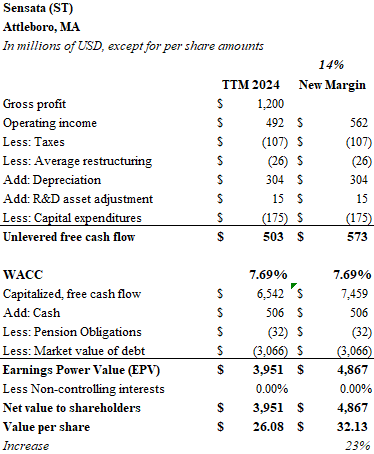

Revenue for the Attleboro, Massachusetts firm has plateaued at $4 billion over the past three years. Operating margins have declined from 17-18% levels prior to Covid, to around 13% today. Tracking the trailing twelve-month period ending in September of 2024, unlevered free cash flow at Sensata was about $500 million. Using a weighted average cost of capital of 7.69% for the business leads to an earnings power value of $3.95 billion after accounting for about $2.6 billion of net debt. On a per share basis, this is around $26, or slightly below last week’s $29 level.

If Sensata can just lift margins by a couple of percentage points (easier said than done) from 12.25% to 14%, free cash flow would increase to $573 million, and translate into over $900 million of shareholder value. This puts the stock in the $32 range. That’s only about 7% above the current price, but the exercise shows the direction management may be headed. Others have noted that some business lines may be sold.

There’s danger in blindly following a fund manager’s latest 13D or 13F filings. People tend to focus on one or two names rather than seeing the big picture. Elliott’s latest filings include a diverse array of holdings. They also disclose many hedges – put options on many sector ETF’s rank among the firm’s many positions. Filings are historical. Elliott could have sold Sensata shares last week. We won’t know for a couple of months.

I will say that in a market that continues to trade on price-to-sales hopium, it is refreshing to actually find a US company selling near it’s intrinsic value using the straightforward earnings power value methodology. Sensata is reasonably priced. The downside appears to be protected. In the case of both Southwest and Sensata, Elliott’s investment thesis of operating margin improvements will translate into tangible business performance and shareholder value.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.