Evolution AB is a Swedish gaming company that trades on the Stockholm bourse. About 622 krona will buy you a share, and that price gives Evolution a market capitalization of about €11.6 billion. Evolution develops and operates games that “sit behind” many well-known gambling sites. They continually find new dopamine-enhancing ways to keep punters glued to their devices, losing money to the house in rapid-fire succession. Most games seem to target the unsophisticated bettor. “Coin Flip”, “Cash Hunt” and “Crazy Time” are just a few of the offerings. More interestingly, they also offer traditional casino games like poker and roulette by hosting players online with live studios situated around the world.

I passed on Evolution earlier this year, but I decided to take another look at after reading a recent Bloomberg article about the investment activities of Kenneth Dart who is taking large positions in the gambling industry through Evolution and Flutter. Flutter owns FanDuel, Paddy Power Betfair, SportsBet, and Poker Stars. Or, if you prefer, just about half of the kit sponsors for English football. In a clear indication of modern society’s moral compunctions, England has banned alcohol sponsors on their team jerseys for well over a decade, but they have no problem with gambling companies emblazoned across players’ chests.

Kenneth Dart is the billionaire heir to the plastic container fortune. When he’s not crafting ways to avoid paying taxes, he is busy investing in “sin stocks”. He had a phenomenal run of success with tobacco firms recently. The thesis seems to be similar for his investments in online gambling: it’s widespread, increasingly legal, and totally addictive.

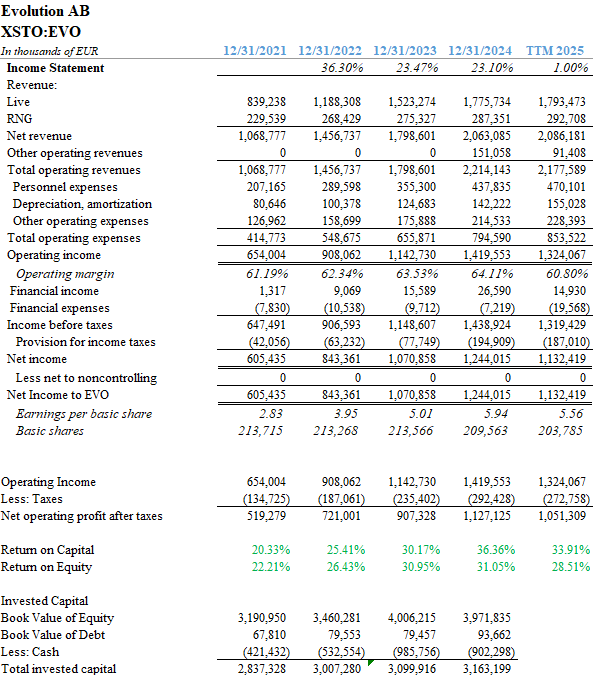

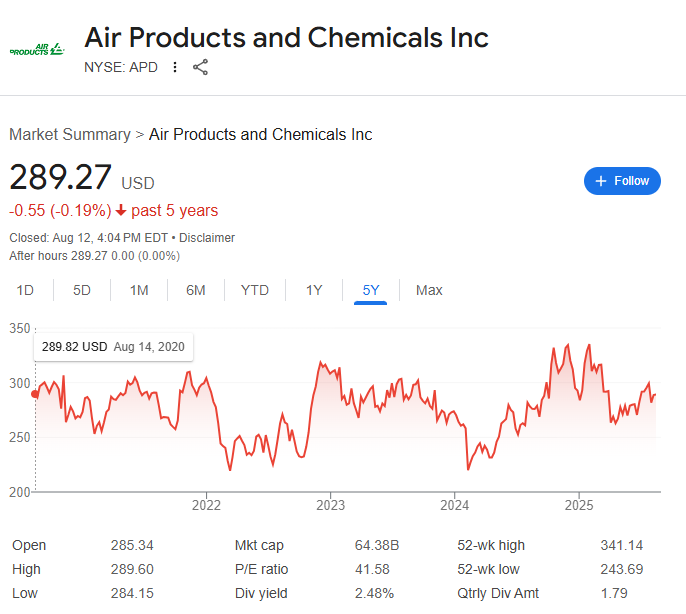

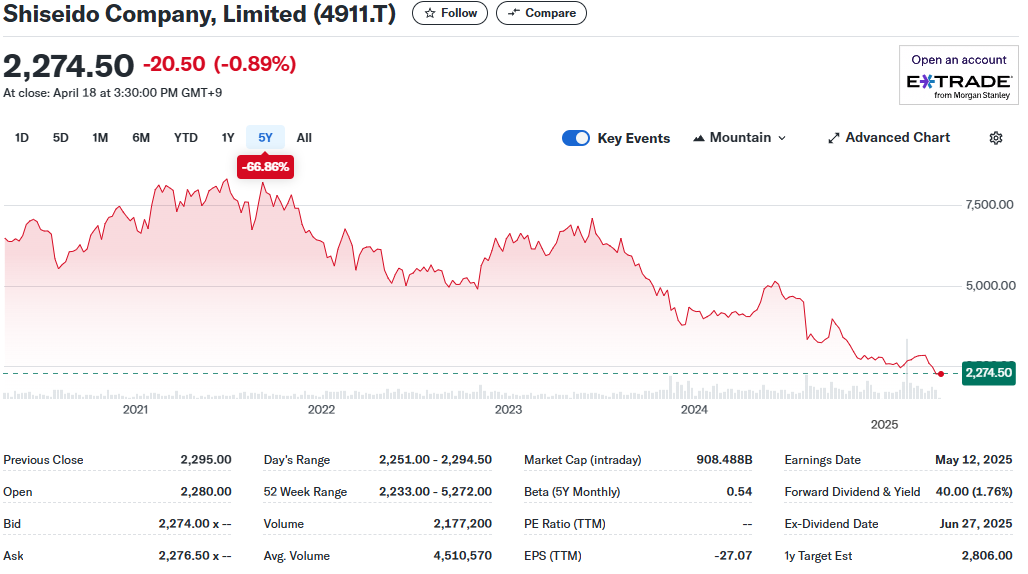

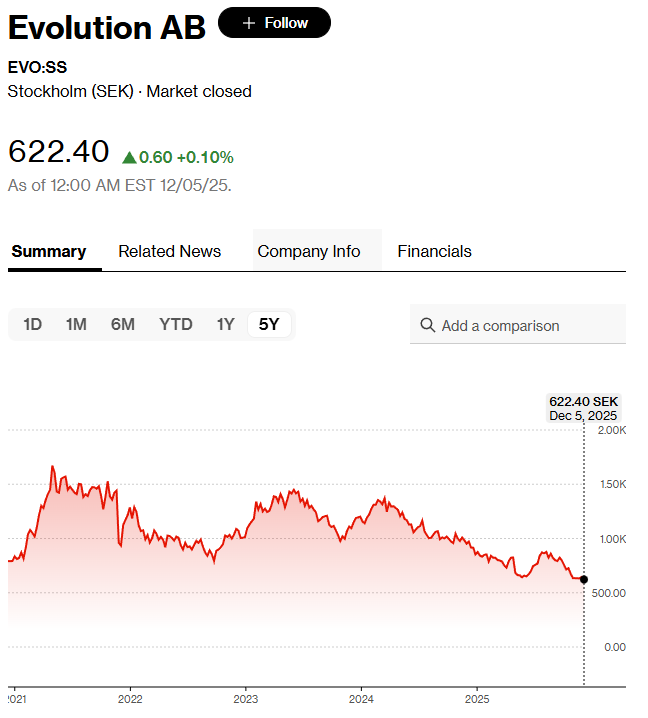

Evolution trades with a trailing PE slightly above 10, and an EV/EBITDA multiple of 7.4x. After a brief summer rally, shares hover near 52-week lows. Evolution is 62% below its all-time Covid high, and down 26% since the beginning of 2025. Notably, Dart’s largest investment in the company occurred before the most recent drawdown.

Revenues at Evolution grew at a compound rate of over 25% annually between 2021 and 2024. Unfortunately, the combination of high growth and diverse worldwide internet hosting services attracted the sort of nefarious folks who’ve always lurked in the gambling shadows. Hackers in Asia inflicted widespread outages and security breaches upon Evolution last year. Revenue has plateaued over the past 12 months. The stock price reflects the lost momentum.

Evolution’s leaders assure shareholders that the security problems have been solved and the company is ready to grow once again. I have found CEO Martin Carlesund’s messages to shareholders to be refreshingly blunt in their assessment of the company’s shortcomings. Accountability seems to be part of the vernacular at Evolution. It is a sharp contrast with another downtrodden company I have been researching: DentsplySirona (XRAY).

One might think that straight talk would be needed at a company which has lost 83% of its market capitalization, but that is not the case! DentsplySirona is not only a really horrible name (did they leave out letters to remind us of missing teeth?), the annual report is a load of jargon-filled blather that leaves one wondering if the company is a dental supply company or a multi-level marketing scheme. It certainly makes no apologies for an atrocious capital allocation track record and probably isn’t worth my time putting pen to paper. But we’ll talk about that later. Moving on.

Evolution is asset-light, has an operating margin of 60%, and posts returns on capital in excess of 30%. The company pays a well-covered dividend, and the yield is nearly 5%. If they can right the ship and return to growth, the upside is compelling.

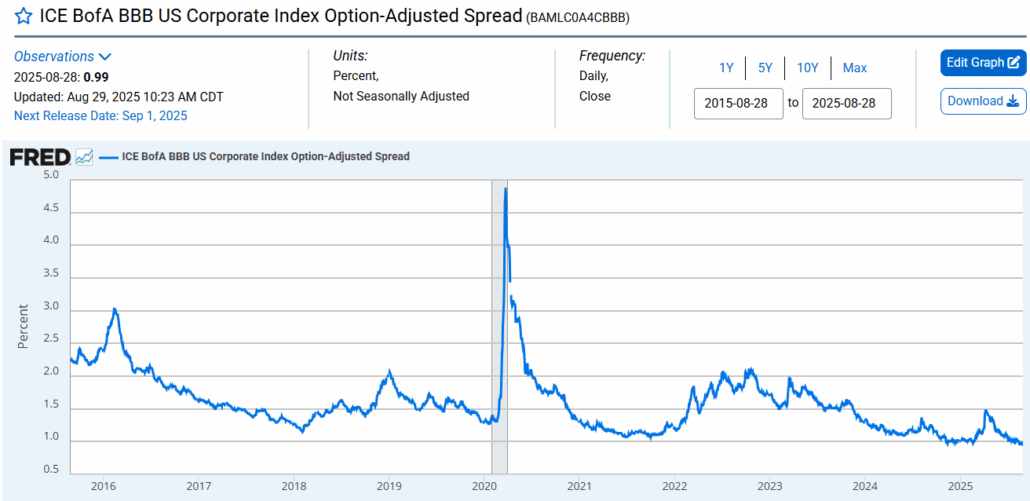

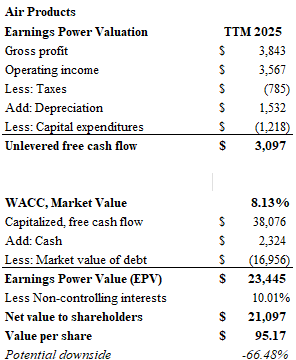

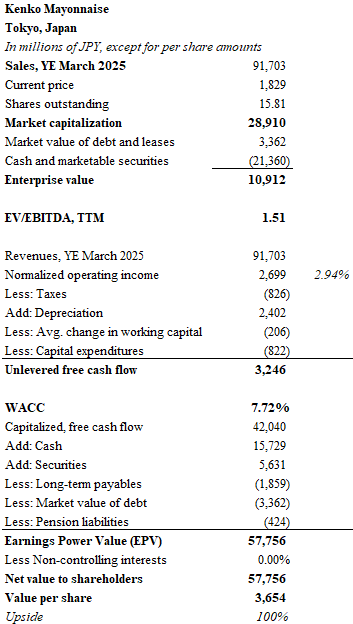

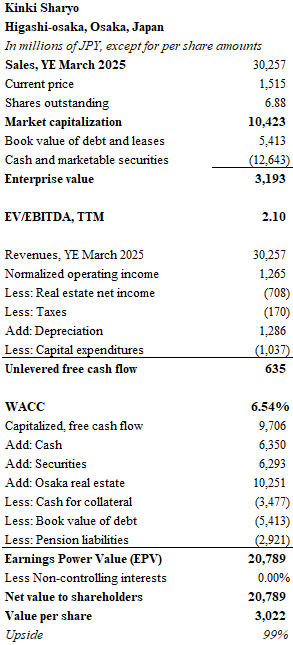

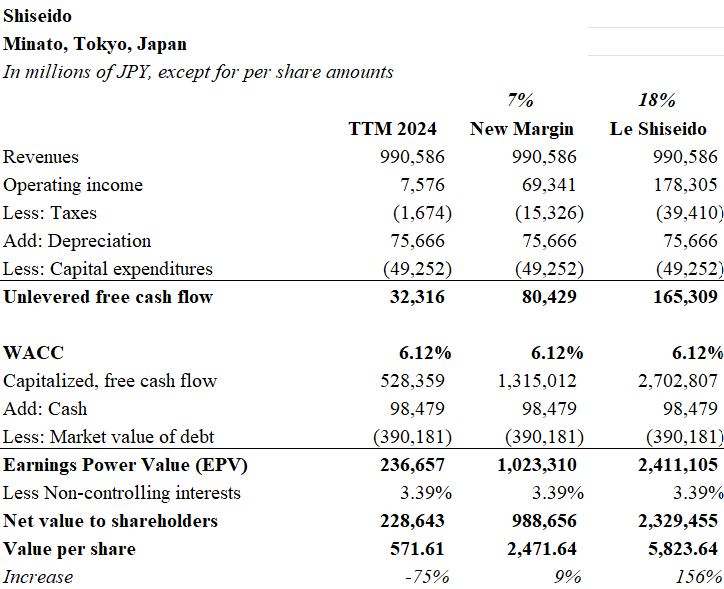

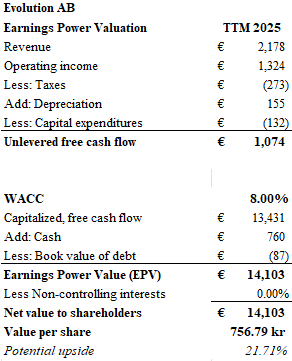

My preferred valuation model is the basic Earnings Power Value (EPV) method advocated by Bruce Greenwald and his peers at Columbia. In the tradition of Ben Graham, normalized unlevered free cash flow is simply capitalized by the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to arrive at a value for the firm. Subsequently, net debt is subtracted to arrive at a value of the equity. In the case of Evolution, unlevered free cash flow over the trailing twelve-month period was just slightly less than €1.1 billion. Using a WACC of 8% to capitalize this amount results in a value of €14.1 billion once one accounts for the net cash position on the balance sheet. On this basis, Evolution trades at a 22% discount to its market price.

As always, I struggle with the proper cost of equity to employ in my valuation. I don’t use betas and assigning a cost to the equity is easier if you can assume a spread above the firm’s cost of debt. Since Evolution is unlevered, the 8% rate has a swaggy feel to it. Should it be lower? This is not a European company. Revenues are international, so pricing off the 10-year Bund doesn’t work. Arguably any company that is vulnerable to hacking and relies on programming talent anywhere from Tbilisi to Taipei should be valued accordingly. Using a WACC of 10% puts the value closer to par.

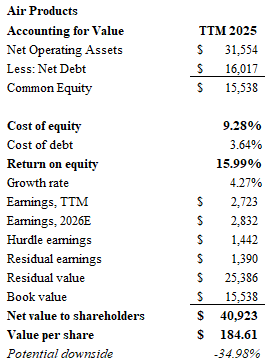

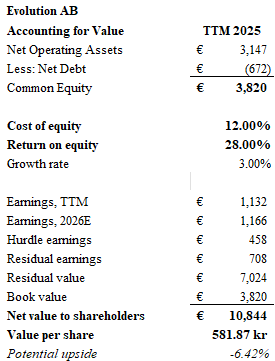

The other valuation model I’ve been using lately is the “accounting for value” method from the book Financial Statement Analysis for Value Investing. Stephen Penman and Peter Pope are CPAs by training and they take book value as the foundation. Next, they add the value of future growth. The authors rightly state that a company’s future growth is only valuable to the extent that the return on equity exceeds the cost of equity. They take this “surplus” return and discount it at the cost of equity less the assumed rate of growth. The higher the growth, the lower the denominator, the larger the value of future earnings. The model can be especially useful if one works backward: it tells you what level of growth is necessary to justify the current price.

If one assumes a cost of equity of 12% for Evolution, and a return on equity of 28% consistent with recent performance, the future “surplus” earnings calculate to €708 million assuming a growth rate of 3%. This results in a value 581 krona per share, once again, roughly in line with the current price.

But what happens if growth resumes at a rate higher than 3%? A 5% future growth rate results in a share value of $705 krona, or 13.4% upside. A 6% growth rate translates into $798 krona, or 28% upside.

Is the market for online gambling going to grow faster than worldwide GDP over the coming decade? It seems plausible. There is an insatiable willingness to gamble on literally everything, and the ubiquitous access to gaming through a phone makes it easily accessible. Might there be a backlash? Names like “Coin Flip” and “Cash Grab” imply a simplicity that can be very appealing to children, so it wouldn’t be surprising if there is a worldwide recognition that the proliferation of gaming is leading to problems with youth delinquency. But sadly, I think that regulatory horse has left the barn.

Evolution has created a lot of valuable intellectual property, its games are entrenched in the gambling site ecosystem, and the investment in live studios provides punters with the authentic feel of a casino. The lack of debt, high dividend yield and substantial margins seem to present downside protection. I believe the returns on equity are significant enough that the firm can reinvest its ample cashflow into growth that will exceed 5% over the next decade, so I consider the shares of Evolution to be priced 10-25% below the intrinsic value of the business. Fortis fortuna adiuvat.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.