Iron Men

The richest man in the world pondered the unfinished business of his life. Hoping to mend their rift, Andrew Carnegie penned a letter to his former partner. He requested a meeting with Henry Clay Frick, whose towering palace loomed only blocks away from Carnegie’s own Fifth Avenue mansion. The irascible Frick was in no mood to satisfy the old man’s ego. He received the hand-delivered note, wadded the paper and tossed it back to the messenger. “Yes, you can tell Carnegie I’ll meet him. Tell him I’ll see him in Hell, where we are both going.”

Steel is an alloy forged by fire from iron and carbon. Nothing generated more heat and pure carbon than the coking coal of Western Pennsylvania, and nobody made more coke than Henry Clay Frick. Their business alliance provided Carnegie Steel with a ready supply of inexpensive coking coal. Steel from Carnegie’s Pittsburgh empire would form the backbone of America’s industrial revolution.

Carnegie so greatly admired Frick’s relentless pursuit of cost reductions that he proposed that the coke baron should become the boss of his steel business. Carnegie awarded Frick shares in the company. Frick could be tyrannical, but his methods proved successful. Carnegie Steel’s production and profits soared.

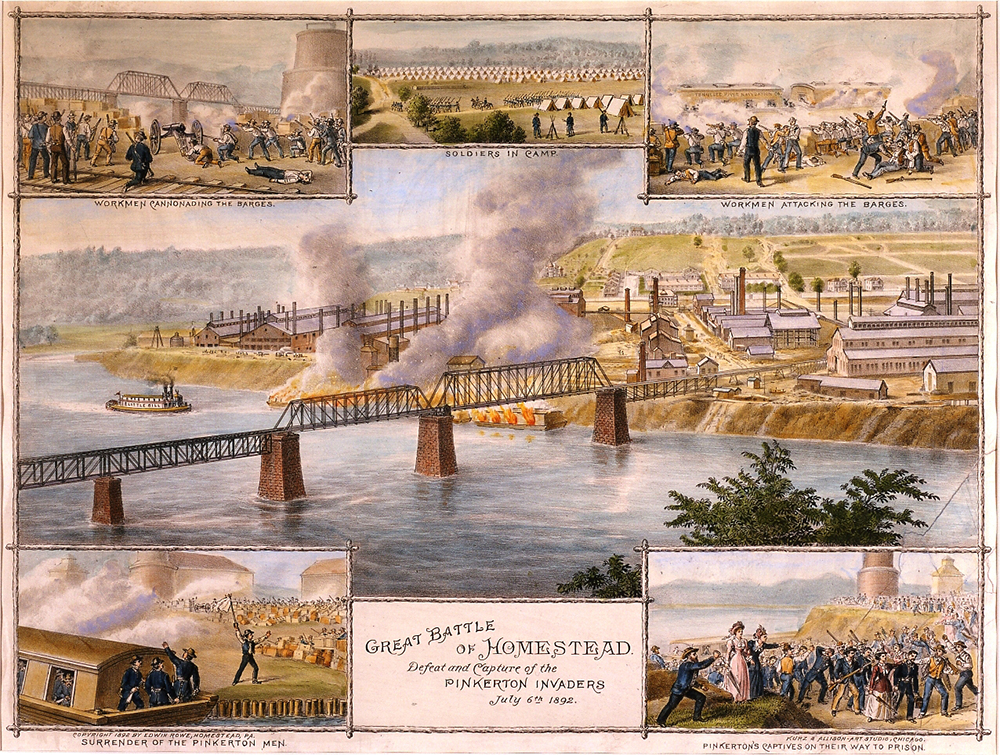

But relations between the two industrial titans became testy. Frick’s involvement in the dam failure that caused the catastrophic Johnstown Flood of 1889 killing more than 2,000 set Carnegie on edge. His violent repression of the 1892 Homestead strike tarnished Carnegie’s reputation. They argued endlessly over the price increases for Frick’s coke. Finally, Carnegie invoked the “Iron Clad Agreement”, a long-dormant business clause which provided a mechanism for a partner’s removal from the business. By January of 1900, Frick was out.

Iron has always been synonymous with strength. Herman Knaust chose the name Iron Mountain for his record-storage business in upstate New York during the 1950’s. As corporations produced millions of paper documents, their safe preservation became paramount. Knaust saw the need to store them in a secure facility where they could not be damaged by fire, theft, or even atomic blasts.

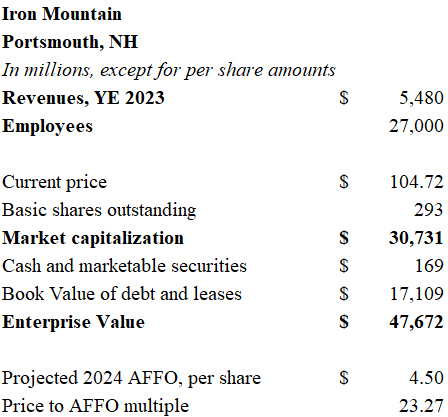

Iron Mountain (IRM) has grown to become one of the world’s leading document and data storage companies with over $6 billion in revenues over the trailing twelve month reporting period ending September 2024 (TTM3Q). Storage generates 62% of revenues, and the remainder comes from services, including document processing as well as the de-commissioning and disposal of used IT equipment. Despite the high concentration of service revenue, Iron Mountain trades as a real estate investment trust. The company has over 7,400 facilities in 60 countries, with 98 million square feet of floor space and 731.5 cubic feet of storage volume.

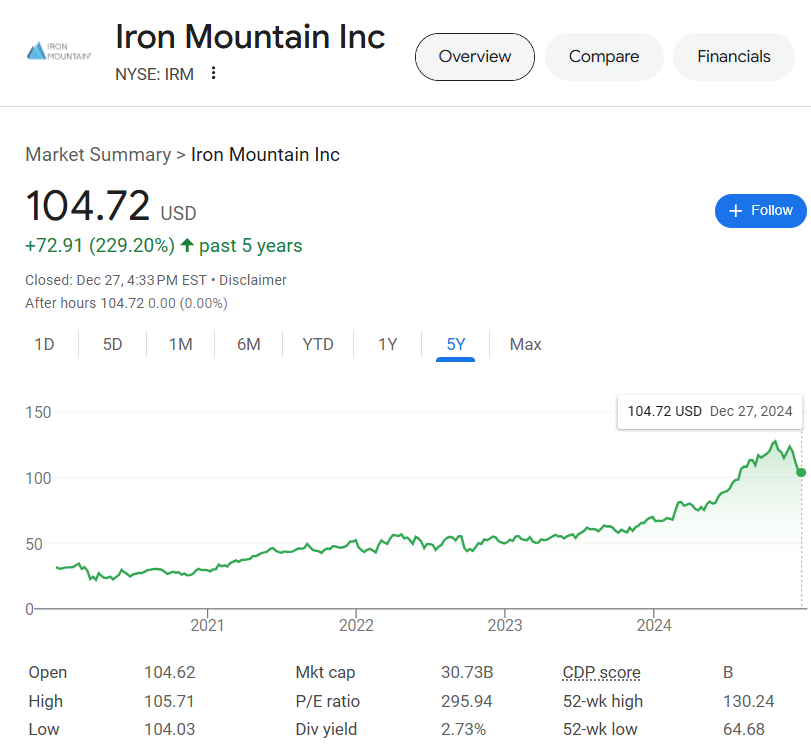

The main attraction for Iron Mountain during the past four years, and its most likely source of growth for many years ahead, is the construction and operation of data storage facilities. These are the buildings that house IT servers and cloud storage infrastructure. The demands for robust computing power for artificial intelligence has set off a race to develop data centers. Iron Mountain aims to be at the leading edge of the AI infrastructure boom.

The current data center portfolio has 26 locations with 918 megawatts of storage capacity. 327 megawatts is leased or under contract, 184 megawatts is pre-leased, leaving 357 megawatts yet to be leased. The company expects 130 megawatts to be leased for the year 2024. At the end of 2023, Iron Mountain had $1.6 billion of development in progress.

Data center construction requires immense amounts of capital. Cushman and Wakefield, a leading real estate advisory and brokerage firm, recently released a 2025 Data Center Development Cost Guide. The average cost to develop one megawatt of “critical load” (building and IT equipment) averaged $11.7 million in the US. In other words, the cost to double Iron Mountain’s data center capacity would be $10.7 billion.

It will be difficult for Iron Mountain to grow its data center portfolio without issuing more stock. The company’s status as a REIT requires it to distribute most of its income, so retained earnings are minimal. Operating cash flow over the TTM3Q summed to $836 million, and $769 million was paid to shareholders.

Iron Mountain equity trades at a market capitalization of $31 billion and debt and leases account for $17.1 billion, giving the enterprise a value of $48 billion. The company is rated below investment grade by Standard and Poor’s at the BB- level. The current weighted average cost of the company’s debt is 5.67%, but additional debt in today’s current rate environment would cost IRM 6.7%. Additional leverage is not a prudent source of capital unless it is paired with the issuance of new stock.

At today’s market price of $105.73 per share, Iron Mountain trades at a 45% premium to its intrinsic value.

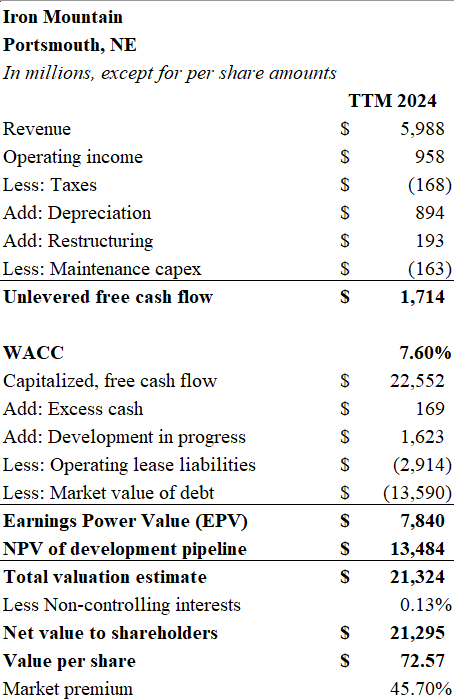

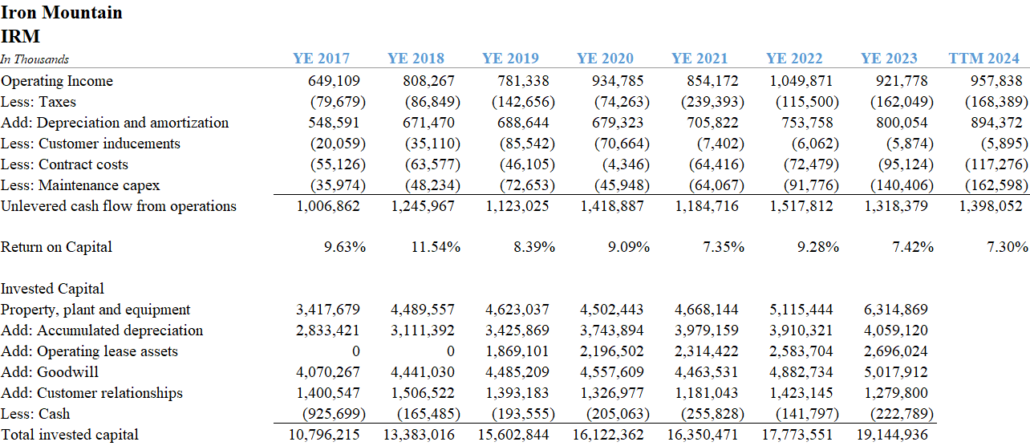

I’ve taken a two-step approach to arrive at a value of Iron Mountain’s equity closer to $73 per share. Using the earnings power valuation (EPV) method, I took the free cash flow for the business and discounted it at the weighted average cost of capital of 7.6%. The aforementioned 6.7% cost of debt (5.53% after taxes) account for 34.8% of capital, and 8.7% was used as the cost of equity. I simply priced equity 2% over the market cost of debt. Unlevered free cash flow of $1.7 billion capitalized at 7.6% is $22.5 billion. Subtract the market value of debt and leases ($13.59 billion and $2.91 billion, respectively), and the net EPV is $7.84 biilion.

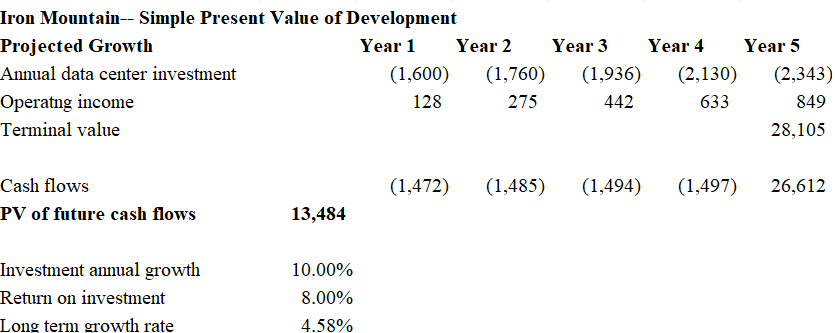

Next, I went fishing for the simplest possible explanation for the gap between the market value of the business and the intrinsic value of its current assets – the unknown future development pipeline. I created the most basic discounted cash flow projection possible. I assumed that IRM placed a development pipeline into service that started with $1.6 billion in Year 1 and grows by 10% annually over five years. I assumed the data centers earn an 8% yield on cost. The terminal value of the business reflects perpetual growth at the current Treasury 10-year yield. The present value of future cash flows, discounted at 7.6% amounts to $13.5 billion. The net value of these two figures, after adjusting for noncontrolling interests is $21.3 billion, or $72.57 per share.

Readers may say that my discount rate is too high. After all, institutional quality real estate continues to trade at capitalization rates between 5% and 6%. I would argue against a lower discount rate for two reasons: One, the faster that the world embraces digital data, the more IRM’s legacy businesses of document processing, storage and destruction diminishes in value. Two, the discounted cash flow model, while laughably over-simplistic, is also generous. Few institutional real estate developers earn much more than a 6% yield on their costs in the current environment. More importantly, my model makes no allowance for the rapid depreciation of the equipment and possible obsolescence of the facilities as more sophisticated ones are built.

Frankly, my earnings power valuation is also quite generous. I add back restructuring charges, despite their seemingly recurrent nature. The company has incurred nearly $670 million in restructuring charges since 2019. I make a deduction for the ongoing capital needs for the facilities, but no deduction is made to unlevered free cash flow for the “customer inducements” and “contract costs” that exceed $100 million annually. These charges appear among capital items rather than on the income statement where they probably belong.

More conventional metrics also point to Iron Mountain’s inflated valuation. The company offers a 2.7% dividend yield – thin gruel in a market where 10-year TIPS can be bought with a 2.23% handle. Meanwhile, IRM trades at 23.5 times adjusted funds from operations (AFFO) projected to be $4.50 per share for 2024.

Iron Mountain will be forced to raise equity in large amounts to fund the data center program. The additional shares will be highly dilutive if the investments can’t yield more than the cost of capital.

Iron, carbon, steel, silicon…the future beckons.

Until next time.

Note: Meet You in Hell is an entertaining book by Les Standiford, published in 2005, that chronicles the formation and dissolution of the relationship between Carnegie and Frick. Chapter One colorfully describes the “letter incident”.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.