Craftsmanship

Boston real estate was feeling pretty sore in the early 1990’s. Many state-chartered banks in New England had collapsed under the weight of so many bad commercial real estate loans, just like their savings and loan brethren throughout the southwest. I first stepped into this troubled market by briefly working for a small real estate brokerage office in Boston.

We got a call from a man who was interested in selling his retail condominium. Wearing my coat and tie, I went with Peter, whom I considered a grizzled veteran even though he was probably only around 35. I didn’t even know about the existence of commercial condominiums. It was a first-floor space in a 1920’s brick building with large glass display windows. Despite the architectural charms, we didn’t think there was much of a market for a 2,500 square foot storefront with on-street parking.

The door opened with a jingle. Wood floors, high tin ceilings, and old brass lamp fixtures illuminated the room. The smell hit you right away. A sharp odor. Turpentine. Acetone. Oil. But it slowly faded into warm woodiness. Like an old church reassuringly scrubbed by parish ladies bearing buckets of Murphy’s oil soap and tins of carnuba wax.

We were met by the owner – a man who was probably in his early fifties, slim and athletic. He had wiry gray hair, sharp blue eyes and the kind of wrinkles you see on runners who have spent a lot of time in the sun. We reached out to shake hands and were clumsily met by his left which he cupped around the knuckles of our outstretched rights. I tried not to look too closely, but his right hand hung limply at his side.

After the awkward introduction, we soon realized we had entered the man’s cathedral. Before us stood row after row of heavy wooden desks – maybe 20 in all. Each one was a masterpiece of carved rosettes, scrolls, leaves, vines and columns. Mahogany pantheons stood among castles of walnut and majestic oak temples. Weighing hundreds of pounds, and much more expensive than any commission check that we stood to earn from a sale, these furnishings were destined for Back Bay mansions and State Street banks.

We learned the owner had suffered an accident on his bike that caused paralysis in his right arm. His career as a carpenter and craftsman was over. He had no partner or apprentice, and his children had moved on. He answered our real estate questions with grim stoicism, but his eyes sparkled once we asked him to show us his inventory. Was he at peace with his tragic misfortune? We took down his information, made some measurements and told him we would call with a proposal to list the space for sale.

I remember buckling the seatbelt when we got in Peter’s car. A small voice inside of me told me to go back and ask the man to teach me to continue his business. I could be his apprentice. This urge came despite my entire woodworking experience consisting of a single semester of shop class in seventh grade. He may have been flattered by my offer, but he would surely know his craft was more than a skill to be taught. It was art. Was I an artist?

As you grow older, you begin to wonder how different your life might have been if you had chosen different forks in the road. The furniture would have been magnificent. The finished product something to behold. Maybe I’d be the one looking for a woodworking apprentice today. Someone to carry on my craft.

Then you realize that every path is painful. How many desks could I have sold, really? All those hours sanding, carving, chiseling, and finishing. The dust, fumes, and bloodied fingers. The greedy lumber mill, the client’s bounced check, the revival of midcentury modern and Restoration Hardware. There’s no easy path, as fanciful as it may seem. Yet it was art. Something tangible. Not just numbers on a spreadsheet.

Ah well, off to the spreadsheets we go.

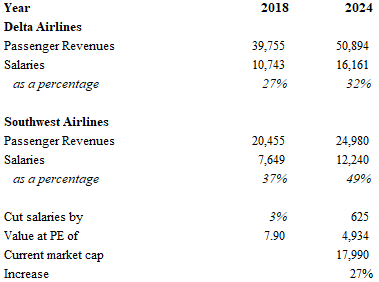

Elliott Management has received much notoriety for its activist shareholder campaigns. In recent weeks Paul Singer’s fund has taken large stakes in BP, Phillips 66, Honeywell, and Southwest Airlines (LUV). Although the firm chalked up a big win at Starbucks last year, two campaigns were less successful: A 2023 shake-up at Goodyear yielded no investment gains. Meanwhile, shares of Sensata (ST) have fallen 12% after an initial surge during May 2024’s announcement of a cooperation agreement between management and the fearsome investment firm. Elliott gained a board seat and pressed for the replacement of the CEO after a series of acquisitions that failed to deliver positive results.

I enjoyed some investment success several years ago when Elliott pressured Cabela’s to sell to Bass Pro Shops, so I am always tempted to follow Singer’s moves. Sensata trades 32% below its 52-week high, and it caught my eye. Goodyear turned out to be a rare blemish for the Elliott team. The tire business is plagued by shrinking margins and brutal competition from Asian manufacturers. Sensata is different. Sensata produces sensors and electrical protection components that have unique technological sophistication. Moreover, the adoption of hybrid and electric vehicles has increased demand for Sensata’s products.

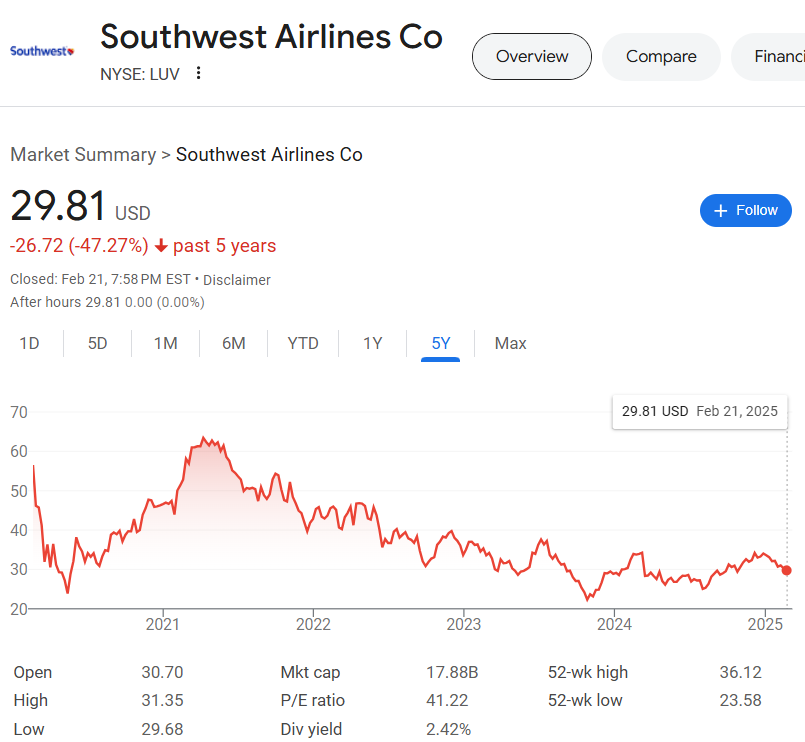

How will Elliott’s scheme play out? For my valuation exercise, I’m purely focused on the possibility of improved operating margins. This is Elliott’s playbook for Southwest. Last week, Southwest announced that they would conduct the first major layoff in the company’s history. They expect to cut salaries, primarily in the corporate offices, by 15%. This is part of an effort to save $500 million annually by 2027. Comparing salary margins at Southwest versus Delta Airlines, it’s not hard to see where value can be created.

Looking back to the peak of Southwest’s market capitalization in 2018, salaries accounted for 37% of passenger revenues. Meanwhile, salaries at Delta amounted to 27% of passenger revenues. Six years later, Delta’s wage bill has risen to 32% and Southwest’s surged to 49%. There’s no argument to be made that Southwest can match Delta. But can they cut salaries back to 46% of passenger revenues? That seems very likely. Such a reduction would boost profits at Southwest by $625 million. Assuming a post-tax multiple of 7.9x translates into $5 billion of market capitalization for LUV, or just about 27% above current levels.

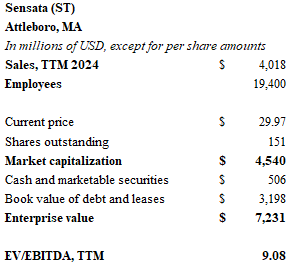

How about Sensata? What kind of value creation can margin improvement deliver?

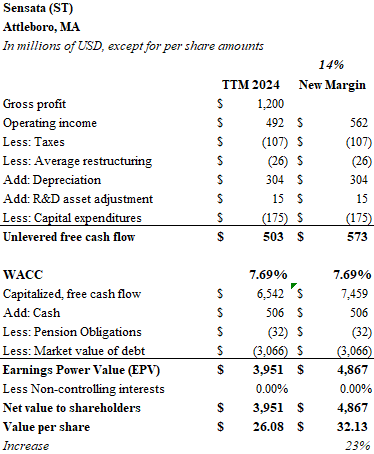

Revenue for the Attleboro, Massachusetts firm has plateaued at $4 billion over the past three years. Operating margins have declined from 17-18% levels prior to Covid, to around 13% today. Tracking the trailing twelve-month period ending in September of 2024, unlevered free cash flow at Sensata was about $500 million. Using a weighted average cost of capital of 7.69% for the business leads to an earnings power value of $3.95 billion after accounting for about $2.6 billion of net debt. On a per share basis, this is around $26, or slightly below last week’s $29 level.

If Sensata can just lift margins by a couple of percentage points (easier said than done) from 12.25% to 14%, free cash flow would increase to $573 million, and translate into over $900 million of shareholder value. This puts the stock in the $32 range. That’s only about 7% above the current price, but the exercise shows the direction management may be headed. Others have noted that some business lines may be sold.

There’s danger in blindly following a fund manager’s latest 13D or 13F filings. People tend to focus on one or two names rather than seeing the big picture. Elliott’s latest filings include a diverse array of holdings. They also disclose many hedges – put options on many sector ETF’s rank among the firm’s many positions. Filings are historical. Elliott could have sold Sensata shares last week. We won’t know for a couple of months.

I will say that in a market that continues to trade on price-to-sales hopium, it is refreshing to actually find a US company selling near it’s intrinsic value using the straightforward earnings power value methodology. Sensata is reasonably priced. The downside appears to be protected. In the case of both Southwest and Sensata, Elliott’s investment thesis of operating margin improvements will translate into tangible business performance and shareholder value.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.