Physics was never boring. At least not when Richard Feynman was teaching. Despite the complexity of his subjects, he kept things simple and fun. Feynman was awarded the 1965 Nobel prize for his work on quantum electrodynamics. His method for learning a topic was to be able to write about it in such a way that a 12 year-old could understand. “Anyone can make a subject complicated but only someone who understands can make it simple,” explained Feynman. That’s why I write down my thoughts, theories and formulas for various investments. To learn. To teach myself.

I fall short of Feynman’s dictum of elegant simplicity on most occasions. Never more so than my recent attempt to explain the valuation of Brookfield Infrastructure Partners (BIP) using the firm’s consolidated financial statements. It’s not entirely my fault. Understanding BIP’s organizational chart practically requires a degree in quantum electrodynamics.

I think BIP management prefers things to be as complicated as possible. BIP is a publicly traded limited partnership. They obfuscate the value of their underlying utility, transport and midstream properties through a web of holding companies and partnerships, most of which are offshore. Buffett would surely file BIP in the “too hard” pile.

BIP is far from a monolithic operating company with a series of divisions. BIP is really a loose confederation of businesses – virtually all of them joint ventures with third parties – that pass cash to limited partners only after everyone else takes their cut. BIP limited partner units trade for nearly three times book value despite only having a claim on about 16% of the equity in the collective companies.

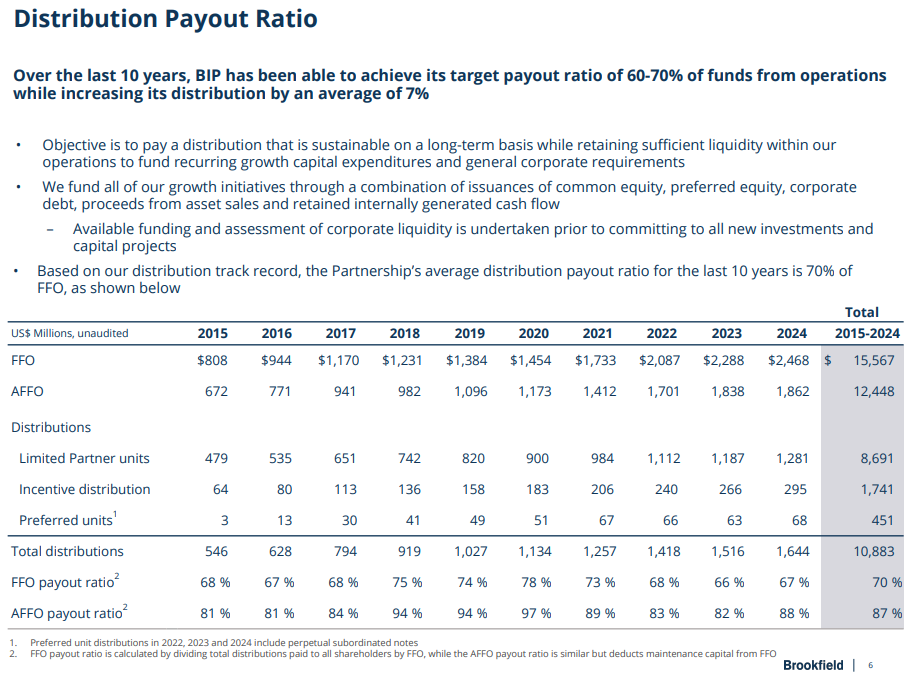

The price is held aloft by a generous 6.23% dividend yield. I concluded that BIP limited partner “equity” is probably just mezzanine debt in masquerade. The company’s allocation of “maintenance capital expenditures” in non-GAAP “adjusted funds from operations” gives investors a flawed belief that dividends are easily supported by operating cash flows.

In short, I am coming around to the thinking of Keith Dalrymple who has produced comprehensive research on the company. He argues that such a holding company structure deserves to trade for book value, and no more. Just like the old Canadian holding company Edper, the Brookfield game is to layer debt at the asset and corporate level and shuffle cash around as needed. Dalrymple’s most recent post explains that BIP is papering over the erosion in net asset value by writing-up the value of illiquid holdings in the accumulated other comprehensive income account.

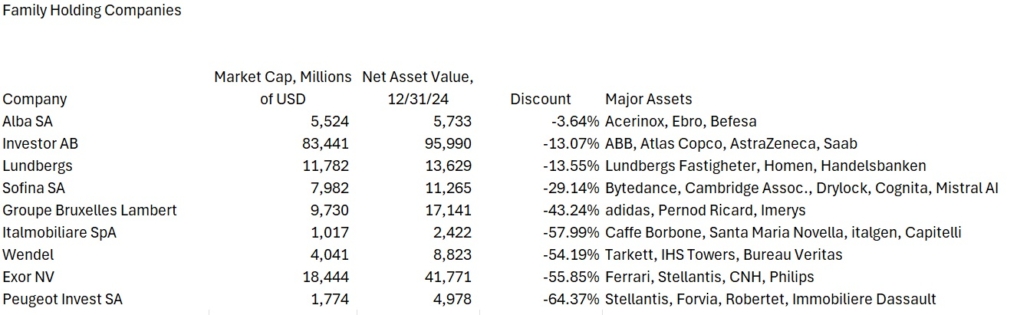

What about other investment companies? Are they trading above book value? I ran the numbers on some large European holding companies. Unlike BIP, the market capitalization for each company is less than the net value of its assets. In most cases, the discount is greater than 30%.

These are mostly multi-generational wealth vehicles for legacy industrialists which also offer shares to the public. The most well-known company is Exor, the holding company for the Agnelli family of Italy, the pioneering family behind the Fiat empire. Exor holds portions of several public and private companies, most notably Stellantis, Ferrari, CNH Industrial and Philips. No, legacy automakers do not inspire much hope these days. However, I would argue that the assets held by the heirs of the Wallenbergs and their ilk are far superior to the Frankenstein that BIP has stitched together among toll roads in Brazil, Alberta LNG factories, and Indian cell towers.

If the holding companies for some of the world’s leading industrial families trade below net asset value, why should BIP sell for a premium?

Tariff Don’t Like It

I am also not Feynman-qualified to lecture on the topic of tariffs. However, I do believe that in the long run, most countries specialize and benefit from what is known as comparative advantage. You want your Swiss making watches, your Italians making pasta, and your Mexicans making tequila. I wouldn’t drink Swiss tequila. If China is producing steel below cost and dumping it in the US, yes, tariffs should apply. But there’s a reason why Bangladesh and Vietnam produce most of our clothes now. We produced most of the textiles of the world in the 1880s to 1900s. I’d prefer to live in the 21st century, thank you very much.

I am traveling in the low country this week. A visit to Savannah got me wondering about cotton. I imagined that the end of slavery meant that the price of cotton rose dramatically after emancipation. Did higher labor costs translate into higher cotton prices after the Civil War? Could that period of history be an analog for 2025?

The opposite happened. Cotton prices dropped. By a lot. Historian James Volo has a well-written summary. There were a couple of reasons for the decline. One, English textile manufacturers responded to the wartime shortages of the American South by sourcing more cotton from Egypt, Brazil and Africa. Two, the cotton gin made production so efficient that the supply of cotton boomed. In fact, American cotton production kept rising until 1937.

What’s the lesson here? Sudden price adjustments might produce unexpected consequences. Bulgarian pasta could just turn out to be a pretty decent substitute for that pricey penne from Pisa. Robot weaving machines in Cleveland might replace millions of Bangladeshi weavers. But that manufacturing renaissance on the banks of Lake Erie? It may not be coming after all. Three programmers in an office building on the outskirts of Hyderabad may control those looms.

Prices send signals to markets. Producers and consumers shift accordingly. Where they turn their gaze is not known with certainty.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.