The Seven Years’ War was the first global war. Battles were fought on three continents as European conflicts spread to colonial territories between 1754 and 1763. Great Britain and Prussia fought an alliance of France, Austria, Russia and Spain. In North America, Britain and France battled on the frontier. Iroquois warriors joined British soldiers against French forces allied with Algonquin and Huron tribes. In defeat, France ceded control of the Great Lakes and Canada.

The Seven Years’ War laid important foundations for the American Revolution. First, the war left Britain with heavy debts. Taxes were levied against the British colonies to replenish King George III’s treasury, sowing bitterness and resentment. Second, the war militarized the colonists. Militias were armed and George Washington and his officer peers trained under British high command. Third, France was eager to avenge her losses, and an alliance with the rebellious colonists would form in the following decade.

In the late days of the American Revolution, with Washington’s ragged army badly in need of a victory, France raised the game. Comte de Rochambeau marched 5,500 troops from Rhode Island to New York where the French Expédition Particulière joined the Continental Army. As French ships prevented a British escape from Chesapeake Bay, forces led by Washington, Lafayette and Rochambeau routed the redcoats at Yorktown, Virginia. The victory was decisive, and independence soon followed.

“Rochambeau” is instantly familiar to many because it is a name frequently given to the game more commonly known as “rock-paper-scissors”. You’ve never heard it called “Rochambeau” before? Me neither. But my friend from Colorado swears by it as does my native-Minnesotan wife.

Why Rochambeau? Was Lafayette the winner who laid some smooth paper on his compatriot’s rock, thus forcing Rochambeau to take command of a grueling march through the mid-Atlantic during the blistering humidity of a colonial summer? Paper always seems to be the sneakiest move. It’s counter-intuitive to win with paper, so light by nature, and it’s just the sort of play a sly bâtard like Lafayette would lay down. Touché.

It turns out there is no proof that Rochambeau ever played rock-paper-scissors, and drawing any connection with the French general is pure speculation. According to the authority on such matters, the World Rock-Paper-Scissors Association, the first mention of a game called Rochambeau appeared in the 1930’s.

Rochambeau is an easy game. Usually, the loser is required to complete some unpleasant obligations like take out the trash, change a diaper, follow Scooby into a haunted cave, or march to Yorktown through swamps and marshes. Government-sponored lotteries are also pretty simple. The winning number is drawn at random. Huge jackpots, microscopic odds. Our governments have been in the gambling business for a long time.

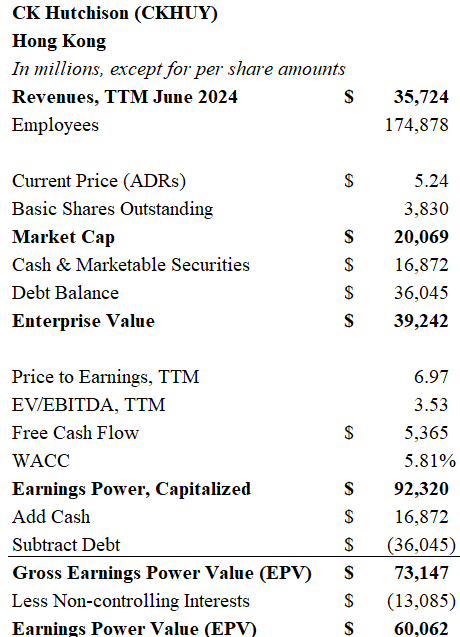

Governments sponsor and benefit from lotteries but they outsource the operations to businesses. The largest publicly traded provider of lottery services is a company called International Game Technology (IGT). Based in London, IGT has substantial operations in Italy and Rochambeau’s old stomping ground of Rhode Island. De Agostini, an Italian conglomerate, controls 42% of the company. IGT runs lotteries, and it also produces gambling technology and equipment. Earlier this year, private equity giant Apollo agreed to pay IGT $4.05 billion for the gaming division with plans to merge it with Everi – another game-tech business. The sale will be completed in the second half of 2025 and will leave IGT as purely a lottery service provider.

Unfortunately, there is no free lottery ticket lying on the ground for buyers of IGT. The price of IGT stock appears to offer no upside to those waiting for the check from Apollo to arrive. In fact, after adjusting for the Apollo transaction, the equity of the combined entity is trading at a 3% premium to the intrinsic value of the lottery business.

The lottery business may be appealing to some because it carries long-term contracts and largely predictable revenue streams. Although point-of-sale equipment is needed, the business doesn’t require a huge capital investment as more of it migrates online. But there lies part of the rub: as more moves online, the gambler’s options widen. Lotteries are a crude game of chance. Why not take a few hits at those wagers which involve “skill” – sports betting and casino games? Certainly, staid old lotteries will lose in the ever-increasing world of online gambling choices.

There are two other problems with IGT: One, the company provides a huge windfall for governments, so naturally it is taxed as such. Tax rates for the company approach 50%. Two, quite a lot of the profits go out the back door through a series of joint ventures. Non-controlling interests grab about 47% of the value.

So, what’s left for the shareholders? You’ve got a lottery business with $2.5 billion in revenues. Operating margins are about 27%, but the taxman taketh 50%. There is about $600 million of free cash flow remaining which can be capitalized at a rate of 7.2%*. Adding $4.05 billion of cash to the net debt of $5.16 billion, results in an equity value of $7.17 billion. Noncontrolling interests have a claim on 47%, so the lottery business is worth about $3.8 billion to shareholders. Meanwhile, the market cap of IGT equity is about $3.9 billion today.

Note: Between the time this article was drafted last week and published today, IGT dropped 6%.

IGT may be worth keeping an eye on. If the market continues to trade the business lower, a discount could emerge. Right now, the odds favor the house.

Until next time.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided in this article is based on the opinions of the author after reviewing publicly available press reports and SEC filings. The author makes no representations or warranties as to accuracy of the content provided. This is not investment advice. You should perform your own due diligence before making any investments.

*Weighted average cost of capital was determined with the assumption that the company’s optimal capitalization is 35% debt and 65% equity. IGT carries a BB+ S&P Rating and therefore has an approximate 6% cost of debt. The figure of 9.06% was calculated as the cost of equity.