A couple of years ago I published my views about the supply and demand of multifamily rental housing in the Omaha metropolitan area. My conclusion was that softness would appear by late 2017 due to an acceleration of supply. I have been pleasantly surprised by the continued strength of the market. Occupancy levels are at 95% or better in most parts of the city.

Unfortunately, the day of reckoning has only been postponed, not cancelled. I believe 2018 will be the first year since 2010 that landlords will be caught short-handed. While I don’t see vacancies rising to the 10%-plus levels we experienced during the dark days of 2004-06 when just about anyone with a pulse was purchasing a house, any pullback in occupancy will feel painful simply because we haven’t been exposed to much adversity in recent years.

Omaha has become large enough now, at nearly 950,000 people, that submarkets can have widely disparate experiences. Northwest Maple Street is an entirely different beast from the Blackstone neighborhood. However, on a macro level, a decline in occupancy of 2-3% seems possible.

There are two reasons why my prediction of market softness has been delayed until 2018. Omaha has grown faster than I thought and developers have been mindful of delivering units at a slower pace.

On the supply side, it’s hard not to ignore the revival of midtown Omaha. Over 1,200 apartments are under construction or just opening south of Dodge and east of 72nd St. Prudent builders released units to the market more slowly than anticipated, however, and the real impact will be felt in 2018 and 2019 when major projects in Blackstone, Aksarben Village and other midtown neighborhoods hit the streets.

On the demand side, population and employment growth have been stronger than I thought possible. We have exceeded 1% population growth for the past few years with a high degree of contributions from international and domestic migration.

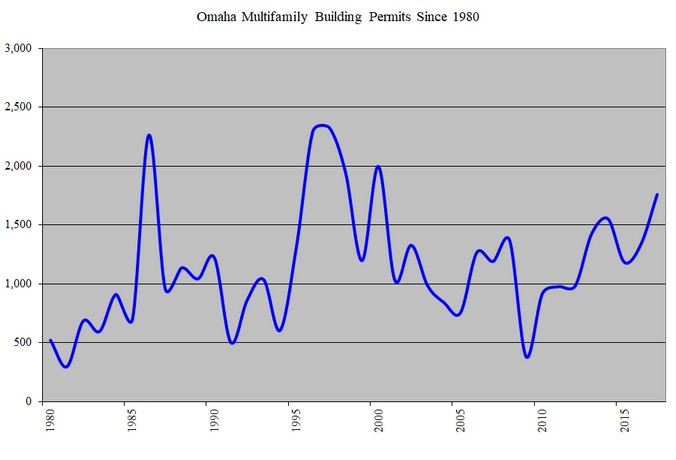

My theory has been for many years now that Omaha can absorb 1,200 apartments per year without disrupting decent rent growth in line with inflation. During the recession multifamily permits dropped precipitously to just over 300 units in 2009. Pent up demand and pinched supply signaled a robust market from 2010 – 2016. Now supply is exceeding the 1,200 unit “magic number”. By 2019, Omaha could experience a glut of 2,000 apartments. In the grand scheme of all rental housing, this amounts to about a 2-3% weakening in occupancy levels. This is not disastrous when taken in the context of the metro area.

The pain will be be felt at the top end of the market. The 2,000 unit overhang will attempt to command units nearing $2 per square foot due to the massive building cost and land inflation since 2013. Geography matters. East Omaha will suffer the brunt of the weakness. Developers are correct to recognize the trend towards urban living. It’s unfortunate that they all decided to recognize the trend at the same time.

Like most booms, the story is more about cheap money than it is about demographics. There was a moment this past summer when the 10 year Treasury bond yield began to head towards 3%. Cassandras who had been warning for years that hyperinflation was lurking just around the corner and gold was a safe haven, suddenly began to sound like they were on to something. But as the summer waned, the Treasury dropped to nearly 2% again. It is only about 2.3% now. This rate reprieve has given green lights to many new projects.

Forecasting interest rates is a fool’s errand, but what can not be disputed as we enter our 10th year of extraordinary central bank intervention in the money supply, is that asset price inflation has been rampant. Stock market multiples are as high as they were during the dotcom bubble. If you call a broker looking to purchase an investment property today, you will go straight to voicemail.

The problem is not one of America’s sole making. The Federal Reserve is planning to decrease its purchases of agency bonds and Treasuries. Under normal circumstances, this would signal a dramatic rise in rates. But America does not operate in isolation. Japan, Europe and China have been increasing their supply of money at an ever faster pace. If the US Treasury rises to 2.75%, a fund manager in Zurich will surely be buying when the alternative is less than 1% domestically. The yield on American bonds can not escape the gravity of sub – 2% yields elsewhere. The international market for capital won’t let this US diver come up for air.

The truly international scope of cheap money infects housing as well as securities. Try bidding on properties in San Francisco, Sydney, Vancouver or Toronto and you’ll see what I mean. Even in Omaha, the numbers are distorted. When developers can continue to borrow money at cheap rates, the estimate of risk gets diminished.

I identify five major risks threatening the Omaha apartment business today: The first is the persistently low interest rate cycle. As mentioned above, the cheap cost of capital is giving green lights to developers who might have otherwise tapped on the breaks by now. The second is student loan debt. Young people are the lifeblood of new apartments. They are under tremendous financial pressure today due to the enormous amount of college debt that’s been incurred. While we have a robust economy with local unemplyment rates hovering near 3% today, a slowdown in the economy would stall wage growth and diminish the affordability of high rents. Student loan debt has surpassed the eye-watering level of $1.4 trillion dollars. Yes, that’s trillion with a “T”. Number three is the challenge facing university enrollment. UNO has been growing but is nowhere near it’s target of 20,000 students by 2020. Small colleges are shrinking or disappearing (Grace University is the most recent casualty). National college enrollment peaked in 2011. Fourth, the possible limitations on international workers from the current administration could dampen population growth. Omaha grew by 9,800 people in 2016 and over 1,000 represented international migration.

The fifth challenge facing apartments deserves its own paragraph. The apartment market must also compete with its big brother: the single family home market. The very slow recovery in single family home starts has worked in the apartment market’s favor. Peaking near 6,000 units during 2005, the supply of houses has only now climbed back above 3,000 on an annual basis. The lack of inexpensive new homes has prolonged the renter experience. But this trend will reverse if the economy stays strong and wages continue to grow. Single family permits are on an upward trajectory. When coupled with multifamily permits, the entire supply of housing is exceeding levels not seen since 2008. The same low interest rates that help apartment developers are the double-edged sword that drives house affordibility.

What’s more, I do not subscribe to the belief that there has been a permanent paradigm shift away from homeownership. Young people still want to start families. When they have children, and if they have the means, they will move to Elkhorn and Sarpy County where pristine schools beckon. Homeownership will probably never return to the insanity of the mid-2000’s but the dream of owning a home did not vanish from society. Millenials may have delayed their family expansion, but the overwhelming human instincts of procreation and self preservation have not ceased. And there’s no place better than a good suburban home for this most American of pursuits.